Introduction

The Safe System is a concept in road safety which originated in Sweden and the Netherlands in the 1980s and 1990s and has since been adopted in countries and territories across the world (Belin et al., 2012; International Transport Forum/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016; van Schagen & Janssen, 2000; Wegman et al., 2005). It is considered as best practice in road safety internationally (International Transport Forum/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2008). The notion of the ‘Safe System’ requires a change in mindset to adopt a new approach of acting systemically, accounting for the failings of humans to eliminate death and serious injury on the roads. The approach is built on the concept of shared responsibility, involving those involved in planning, building, managing, or using the road traffic system. A traditional approach to road safety tends to focus on reducing the number of fatalities and serious injuries (not eliminating them entirely) and tends to react to specific incidents, rather than proactively targeting risk as in the Safe System. Another fundamental difference is that traditional road safety focuses on dealing with non-compliant road users, rather than accepting that people make mistakes; are physically vulnerable in crashes; and that the road system can be designed to protect in the event of a collision occurring. The concept of shared responsibility moves away from the traditional approach of treating road safety risk through engineering, education, and enforcement delivered in isolation, and instead combining efforts to strengthen the whole system (Bliss & Breen, 2009; Breen et al., 2018; International Transport Forum/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2008, 2016; Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety, 2018; Swedish Transport Administration, 2019; SWOV, 2018; Turner et al., 2016, 2021; Wallbank & Helman, 2021; Welle et al., 2018; World Health Organization, 2011, 2017, 2021).

Many countries have been committed to Safe System thinking for some time (such as Australia) (Corben et al., 2010), whilst elsewhere, the Safe System movement is gaining momentum in countries like the United Kingdom (Department for Transport, 2019; Transport Scotland, 2021). However, “Safe System continues to be impeded by a fundamental differing of views in what it intends to achieve and how it is meant to achieve stated objectives” (Green et al., 2021, p. 179).

If differing perspectives of what the Safe System is exist within, and between, individual authorities, road safety partnerships (collaborations between stakeholders such as police, fire and rescue service, and road authorities), and local and national governments, there is a danger that any dilution of a systematic approach risks compromising safety.

Organisational culture is based on the shared beliefs, values, and behaviours of members of that organisation (Cooper, 2000). It is influenced by relationships, approaches to work, and communication, which all shape perceptions, behaviours, and understanding. If the collective group of individuals within the organisation does not share the values of the system, these actions will not be taken, and the organisation is unlikely to function as intended (Hudson et al., 2000). The way in which organisations deliver interventions out on the roads will be influenced by the internal policies, practices, and decision-making processes of the organisation.

Whilst not explored explicitly in this paper, one potential influence on road safety organisational culture is that road safety violations, particularly Safe Speeds, are often enforced through fines. This could create a dependence on fine revenue for funding road safety programs, in turn influencing speed limit setting and road design to guarantee income. A mature Safe System makes it clear what fine revenue is spent on and has a culture where decision making is based on safety evidence, not the desire of partners to secure funding.

The Safe System is an approach which requires, for many, new philosophical thinking regarding the improvement of safety on the road network. An organisation can state its ambition to adopt a Safe System approach but if the safety culture of that organisation continues to support beliefs and practices that do not match, it will fail to deliver a Safe System.

The aim of this research is to determine if it is possible to create a Safe System Cultural Maturity Model (SSCMM) and accompanying diagnostic tool to assess the readiness of road safety organisations in the adoption and implementation of Safe System thinking and actions. The purpose is to assess the safety culture of individual road safety organisations, and therefore, it is anticipated that the model and the tool will be of assistance to those with road safety responsibility, including road authorities, police forces, fire and rescue services, local and national government, and road safety partnerships. Once a level of maturity has been diagnosed, the organisation can use the findings to identify where improvements need to be made to the safety culture, through changing practice and/or beliefs.

A SSCMM can be used to assess the degree to which the Safe System approach is permeating policy and practice. Based on the establishment of a cultural maturity index, analysis of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, underpinned by a behavioural framework, it can be used to highlight the readiness of road safety organisations in fully embracing and implementing a Safe System approach.

Methods

To create a SSCMM, multiple elements need to be brought together. These include an understanding of Safe System meaning, actions, and what it involves in practice. It also requires an understanding of how to define and measure cultural maturity. A mechanism to enable change within organisations should be identified. Finally, it requires a method for linking the concept of cultural maturity with the specifics of Safe System delivery.

The Safe System element of the model requires the identification of external actions which would be expected to be delivered by an organisation that is culturally mature. To determine what best practice suggests are the required actions to deliver a Safe System, a review of international guidance manuals was undertaken, cataloguing and synthesising identified actions (Bliss & Breen, 2009; Breen et al., 2018; International Transport Forum/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2008, 2016; Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety, 2017; Swedish Transport Administration, 2019; SWOV, 2018; Turner et al., 2016, 2021; Wallbank & Helman, 2021; Welle et al., 2018; World Health Organization, 2011, 2017, 2021).

A total of 16 manuals and guidance documents used internationally were reviewed to identify over 100 Safe System actions. A workshop of road safety experts in the United Kingdom (UK) was held to review the applicability of the 48 most frequently cited actions, determining that these were all appropriate, particularly in the UK setting. These actions are shown in Table 1.

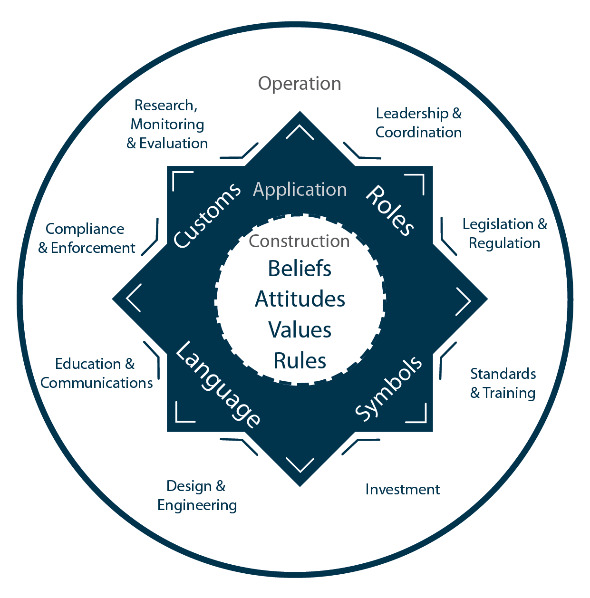

Safe System models often include the mechanisms of change required to deliver actions across the various components. To ensure that the range of potential change mechanisms were identified, a review of Safe System models was conducted. Four Safe System models were examined from: Loughborough University Design School safe system course (Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety, 2017); Australia (Commonwealth of Australia, 2022); New Zealand (NZ Transport Agency, 2016); and Canada (Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators, 2016).

Figure 1 shows an example of a Safe System model, based on characteristics used in the four reviewed models. All tend to include the overall purpose at the centre of ‘Vision Zero’, which is an ambition to eliminate death and serious injury from crashes on the roads. The middle ring of the model sets out the Safe System pillars or components required to create the Safe System. In some models, there are five pillars (Safe Roads, Safe Road Users, Safe Speeds, Safe Vehicles, and Post Collision Response). In other models, an additional pillar of ‘Road Safety Management’ is included. Whilst not necessarily shown in the models explicitly, the Safe System also includes the central principles that:

-

People make mistakes

-

The human body is vulnerable in the event of a collision

-

There is a shared responsibility to prevent death or serious injury

-

The system as a whole combines to reduce the severity of a collision when one does occur

The four Safe System models reviewed contained comparable change mechanisms; there are differences in emphasis and some change mechanisms only featured in single models. The change mechanisms used across these models were grouped into eight overarching change mechanisms for use in the SSCMM and the identified 48 actions arranged according to the change mechanisms. These change mechanisms are:

-

Research, monitoring and evaluation

-

Education and communication

-

Standards and training

-

Design and engineering

-

Leadership and co-ordination

-

Compliance and enforcement

-

Investment

-

Legislation and regulation

With the Safe System defined by the actions identified in international guidance, the other major element of the SSCMM is a method of defining cultural maturity. Cultural maturity has developed in recent years as a method of measuring how developed an organisation’s safety culture is. There is no single definition of ‘organisational culture’ nor is there one for ‘safety culture’; one paper summarised it as consisting of three elements: the person (how people feel, their attitudes, and values); the situation (the organisation’s safety management systems); and behaviour (what people do) (Cooper, 2000).

There are different methods which can be used for measuring and evaluating the safety culture of an organisation. Questionnaires can be used to evaluate the ‘person’ element, whilst auditing and reviewing the safety management system can measure the ‘situation’ and checklists can be used to assess ‘behaviour’. Questionnaires can be used to measure the ‘safety climate’, which describes the attitudes and beliefs of an organisation at a certain time. It means that cultural maturity can improve or degrade, depending on the attitudes and beliefs of the organisation’s members over time.

A review of cultural maturity models used across a variety of sectors were assessed for applicability in road safety (Fekadu et al., 2021; Fleming, 2001; Foster & Hoult, 2013; Hudson, 2001, 2003; Hudson et al., 2000; Hudson & Willekes, 2000; Lingard et al., 2014; Parker et al., 2006; Prochaska, 1995; Reason, 1997; Warszawska & Kraslawski, 2016; Westrum, 1993). Many of the models are not about assessing safety culture on its own but also suggest a strong relationship between the culture of an organisation and the development of a systems approach.

A SSCMM was created, bringing together Safe System components, cultural maturity principles, and thinking on organisational behaviour change. The model is accompanied by a diagnostic tool for use within organisations to determine levels of Safe System cultural maturity.

Safe System components

The Safe System components of the SSCMM were identified by reviewing international guidance and cataloguing the actions recommended; the common components in the literature covering the five pillars; and the actions required to build these pillars. These were aligned to Safe System change mechanisms. Safe System principles focus on human fallibility and fragility; shared responsibility; and the simple imperative that no human being should be killed or seriously injured as the result of a road crash (International Transport Forum/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016; Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety, 2017; Swedish Transport Administration, 2019).

Cultural maturity

Cultural maturity models seek to measure the characteristics which inform an organisation about its safety culture. Grading systems are embedded into models, which indicate where the organisation currently is and can be used to identify ways in which the safety culture can mature.

Eleven cultural maturity models were assessed from multiple sectors (covering safety and occupational health; coal and mining; human resources; nuclear management; and management) to determine applicability. Models tend to follow progressions from a position where there is no or a limited safety culture through to an organisation with safety fully embedded. The applicability of models to the SSCMM were assessed as to determine:

-

Whether the model could be used as a cultural assessment to gauge the level of performance or alignment with specified principles and best practice

-

Whether the model could be used to qualify the characteristics present at each ‘level’ of cultural maturity

-

Whether the model lends itself to systems-type thinking and the integration of different work areas as a measure of operational effectiveness

After assessing existing models, the Hudson and Parker safety culture ladder, or ‘Hearts and Minds’ model (Hudson, 2007) emerged as the most appropriate base model for the SSCMM. Figure 2 shows the levels of maturity defined in the Hearts and Minds model. Westrum developed a Typology of Organisational Culture to distinguish safety cultures, moving from Pathological (where those in the organisation cares more about not getting caught than safety), through Calculative (where logical necessary steps are blindly followed) to Generative where safe behaviour is integrated into everything the organisation does (Westrum, 1993). A safety culture will only exist in the later stages of the model, with earlier stages describing an unsafe or immature culture in relation to safety. In a Generative organisation, all members of staff, including senior leadership will be fully committed to the safety culture.

The Hearts and Minds model extends Westrum’s model to add Reactive and Proactive. In a Reactive culture, safety is starting to become a more important value but beliefs, methods and working practices are still rudimentary. Beliefs that safety is worthwhile can start to be established in the Proactive stage (Hudson et al., 2000).

Whilst Hudson and Parker’s five stages are applicable to road safety with regards to what each stage relates to, we have altered some of the stage labels to align with other maturity frameworks related to Safe System. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has recently created a framework to support low- and middle-income countries in their self-assessment of road safety capacity (Small et al., 2023). The International Transport Forum (ITF) has developed a practical tool to help countries, organisations, and projects to make progress in Safe System implementation from a practical perspective (ITF, 2022). To align these two frameworks with the SSCMM, the three organisations have decided to align terminology and use the five stages of: ‘Vulnerable’, ‘Emerging’, ‘Developing’, ‘Maturing’, and ‘Advanced’.

The descriptions used for the five stages of Hudson’s adaptation of Westrum’s safety culture model can be used to explain how road safety organisations respond to Safe System thinking:

-

Vulnerable (Pathological) – Road collisions are caused by road users’ illegal behaviour. Organisations concentrate on delivering minimal road safety activities required to avoid intervention from regulatory bodies.

-

Emerging (Reactive) – Organisations take road safety seriously but focus on remedial measures after collisions have taken place.

-

Developing (Calculative) – Road safety data are important for directing activities, but Safe System thinking is a management concept and is not present in general working practices.

-

Maturing (Proactive) – Safe System thinking starts to become embedded across the organisation. Road safety is seen as proactive, identifying weaknesses that could lead to collisions prior to them occurring. Collaboration with organisations across the system is key.

-

Advanced (Generative) – Safe System thinking is an integral part of the organisation’s operations, with active participation at all levels. The organisation champions the Safe System philosophy across the road safety sector, working closely with partners and stakeholders.

The Hearts and Minds project commenced in the Health, Safety and Environment sector, with the intention of establishing a workforce which is self-driven or intrinsically motivated to perform safe behaviour. A safety culture will exist with individuals who engage in good practice automatically and where there are no barriers to perform work in the best and safest possible ways. The model relates values to behaviour, and “shows how values underlie beliefs, but also that barriers can ensure that people hold beliefs that mean that they feel incapable of attaining their values” (Hudson et al., 2000, p. 1). It could be that people value safety but also believe that implementing safety measures is expensive or that issues will not occur in their particular environment, so safety issues can be put to one side whilst they concentrate on production. Therefore, the difference between the Hearts and Minds project and other programs is that others have aimed to ensure that people are allowed to perform the right behaviours to be safe. The Hearts and Minds program is designed to act at the levels of values and beliefs (Hudson et al., 2000).

The concept of motivation is central to the Hearts and Minds model, acting as a driving force for behaviour. People can be motivated to act safely but they could also be motivated to act quickly, for their own comfort, or for the profitability of the company.

With Safe System implementation, it is necessary to have well-informed actors who believe in the common goal of the elimination of death and serious injury and are willing to target road risk collectively and proactively. The internal culture of a road safety organisation will influence its priorities and the activities it undertakes externally on the road network.

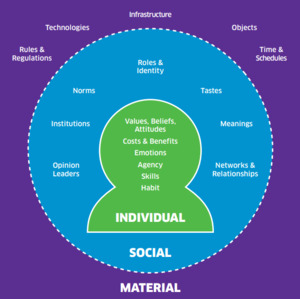

Organisational Behaviour Change

The SSCMM requires a mechanism for operationalising Safe System actions, and a method for shifting values and beliefs from traditional road safety approaches to the adoption of Safe System values and beliefs. The ISM model (Darnton & Horne, 2013) is based on theory and evidence which show that people’s behaviour is influenced by three different contexts: the Individual, Social, and Material, as shown in Figure 3.

At the centre of the ISM model is the Individual. As with the Hearts and Minds model, motivations reflect the values, beliefs, and attitudes of individuals and influence how they behave (Darnton & Horne, 2013). For a shift to Safe System approaches, individuals within an organisation will need the motivations to behave in a Safe System way with the procedural knowledge (know how) and factual knowledge (know what) to apply Safe System principles to the road network. Traditional road safety approaches may be affected by habits, through automatic and frequent activities delivered over time.

Surrounding the Individual in the ISM Model is the Social. To inculcate the Safe System, the social context will need to be one where institutions, leaders, and networks are based on Safe System thinking, in turn influencing norms, roles, identities, tastes, and meanings. The outer context of the ISM Model is the Material. For the Safe System, the materials, technologies, objects, infrastructure, and time will need to be invested by organisations to enable individuals and teams to deliver Safe System interventions.

The ISM model is a useful framework for understanding the contexts which shape the behaviour of individuals and therefore, is useful for assessing Safe System cultural maturity. The model has been incorporated into SSCMM through the question set, providing insights as to where organisations may need to concentrate efforts to improve Safe System culture. The question set explores attitudes (both individual and collective), actions, and processes, reflecting the influences of the individual, social, and material.

The ISM model is a version of the socio ecological model already integrated in Australia into road safety practice. The approach works well for embedding the concept of shared responsibility and identifying the tools and influence required to implement effective policy and practice (Australian Government, 2019).

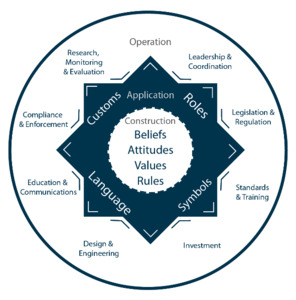

Bringing the models together

To determine the Safe System cultural maturity of an organisation, three models are adapted and combined, as shown in Figure 4: Safe System principles and practice; elements of the Hearts and Minds model (Reason’s characteristics of safety culture (Reason, 1997) and Parker and Hudson’s adaptation of Westrum’s safety culture model (Hudson et al., 2000), moving through five stages from Vulnerable to Advanced; and the ISM Model explaining how values and beliefs can be formed and can influence safety behaviour. In our model, we have chosen the words ‘construction’, ‘application’ and ‘operation’ to describe the elements that influence safety culture.

Reflective of the ISM Model and Hearts and Minds’ model concepts, ‘Construction’ is at the centre of the SSCM covering beliefs, attitudes, and values of individuals towards the Safe System and the rules they must adhere to for Safe System delivery.

‘Application’ is the way we describe the social context of Safe System application using roles, symbols, language, and customs. If application is strong, the organisation will manifest these cultural constructs in the vocabulary it uses, the roles that people in the organisation adopt (both formal and informal), and the customs which develop.

The outer circle of the SSCMM is ‘Operation’, which we propose is comprised of the change mechanisms used to deliver Safe System actions on the roads. An organisation with individuals holding Safe System beliefs and values will talk Safe System talk and deliver it through using all these change mechanisms (in partnership with other actors in the system).

Results

Creation of the SSCMM is not purely a theoretical exercise. The concepts behind it have been used to define Safe System cultural maturity and devise a question set for diagnosis.

Safe System Cultural Maturity Stages

Individuals often struggle to articulate what the prevailing safety culture of an organisation is like; it is more realistic to explore with them the prevalent behaviours (operation) to understand what these reveal about the underlying safety culture. Hudson and Parker’s adaptation of Westrum’s model was used to categorise Safe System cultural maturity, on a scale from Vulnerable to Advanced, probing the operational layer of the model. By creating a set of statements that express the five levels of cultural maturity in language that is relevant to the field of road safety and with a clarity that could be understood throughout the organisation, staff can be helped to evaluate the prevailing level of maturity without needing to describe this for themselves.

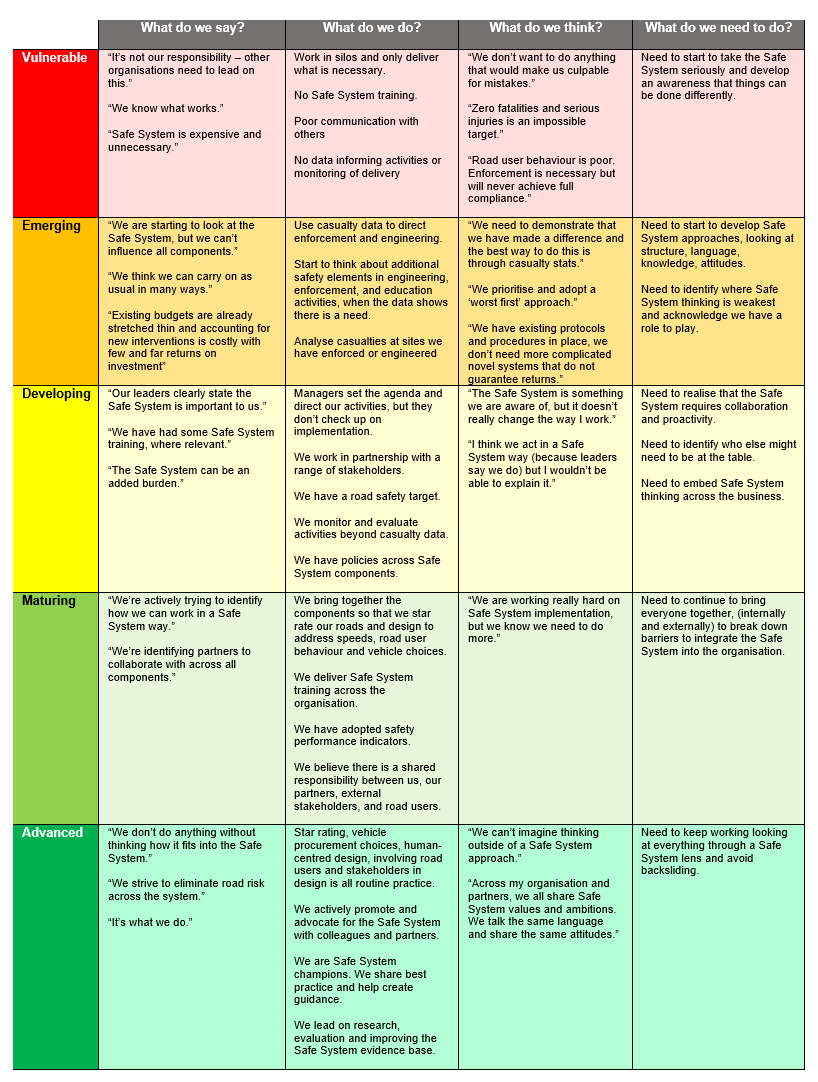

It was important to define the five stages of cultural maturity specifically for Safe System thinking. By describing what an organisation will be doing, saying, and thinking at each stage, it can understand how to progress to become more mature. Figure 5 describes each of the levels in terms of what all staff say, what all staff do, what all staff think, and what the organisation needs to do to move to the next stage. These descriptors in other fields provide details about the expected benchmarking, audits, and reviews undertaken for health and safety (Parker et al., 2006); approaches to leadership and organisational goals and values (Warszawska & Kraslawski, 2016); or risk management in the minerals industry (Foster & Hoult, 2013).

Question Creation

To determine the cultural readiness of road safety organisations, a survey tool was created and tested with a selection of representatives in 10 road safety partnerships and one national road authority from across the UK. A parallel study was undertaken where representatives were interviewed to understand their road safety priorities and issues.

The tool is diagnostic to highlight the current overall health of a Safe System culture; it is evaluative to consider progression (or regression) over time; it is comparative to benchmark against other organisations; and should be transformative, by pinpointing the components, change mechanisms, and actions which remain weak and in need of further improvement.

Each question had five corresponding statements, which describe actions to reflect the five cultural maturity stages. Statements reflecting an ‘Advanced’ position include the implementation of the Safe System actions identified in the international literature, whilst ‘Vulnerable’ statements described an organisation where no efforts were made to implement Safe System thinking in that policy/delivery area. The Hudson and Willekes descriptions were used as a starting point to describe the likely actions, attitudes, and position of an organisation at each cultural maturity stage. An iterative and collaborative process was completed to produce 22 questions and statements, designed to be short and simple and avoid jargon, where possible. The statements also ensure they include the identified Safe System actions, across the Safe System pillars, and include the identified mechanisms of change. The full set of 22 questions cover the SSCMM model components related to Construction, Application, and Operation.

The questions and statements are designed so that a respondent selects the statement they believe most closely represents their organisation for each question. The statements are randomised for each respondent and the cultural maturity headings and scores are not included in the tool, with the respondent selecting 22 statements in total, one for each question. Table 2 provides an example question showing the associated statements to select from aligning with what do we say, what do we do, what do we think and what do we need to do? The intention is that the statements are responded to by many employees performing varied roles across the organisation. This would include senior leadership, middle management, and lower-level staff, covering functions from decision-making to delivery. This will provide insight into the prevailing Safe System cultural maturity and help to diagnose where in the organisation the culture is stronger and where work to improve the culture is required.

Scoring

A scoring method was used for the Westrum Safety Culture Scale, which has also been used in the SSCMM (Hudson & Willekes, 2000). These ranges are shown in Table 3.

Each statement was scored from 1 to 5 to reflect the five cultural maturity stages, with averages calculated across respondents to coincide with the ranges in Table 3. Each question was linked to a Safe System pillar, and the statements included the Safe System actions identified in the early review of international guidance. The change mechanisms used to deliver the actions were also associated with individual statements. By classifying statements by change mechanism and Safe System pillar, it allowed for analysis of scores in multiple ways. For example, the question in Table 2 was linked to the Safe System Pillar of Road Safety Management and change mechanism of leadership and coordination.

Discussion

This study set out to determine if it was possible to diagnose the Safe System Cultural Maturity of a road safety organisation. The SSCMM and survey create a detailed diagnostic output reflective of the organisation’s current alignment to Safe System best practice, pinpointing where construction, application and/or operation need to be strengthened. These organisations will then need to engage in a programme to collectively plan how the prevailing safety culture might be improved. Because the questions link to explicit actions and relevant change mechanisms in the literature, their scores can direct them to target priority actions that will improve Safe System application and enhance the safety culture through use of a standardised tool and will allow organisations to appropriately identify and allocate policy, funding, and training.

The SSCMM is not the only tool being developed to assess Safe System readiness. The World Health Organization has similarly used Hudson and Parker to describe the evolutionary concept of road safety cultures (Iaych, 2022), whilst the ADB has developed a tool to assess Safe System implementation at the country level (Small et al., 2023). The ADB framework helps low- and middle-income countries in their self-assessment of road safety capacity and identify the most useful next steps in development. The ITF has published a guide, which also sets out stages of Safe System development (ITF, 2022). The ITF tool supports countries, organisations, and projects with Safe System implementation from a practical perspective, outlining the different types of activity delivered at different levels of maturity. These tools can sit alongside the SSCMM as complementary approaches, although none of these other tools explore organisational culture and the methods to influence safety culture, instead focusing on actions or capacity building.

All of these tools may experience the same contextual barrier that might prevent their adoptions and efficacy: namely, how to move organisations and countries from the lowest stage of development (where no Safe System principles are deployed) to starting on Safe System implementation. This is particularly pertinent to low- and middle-income countries, where road safety can represent a large public health issue but a low priority for action. General safety culture models may provide a starting point to help such countries instigate their Safe System thinking.

Study strengths and limitations

There are multiple tools which exist to measure ‘safety culture’, with the purpose of informing an organisation about its workforce management systems and how they create safe outcomes. The SSCMM measures an organisation’s adoption of roles, practices, and programs that facilitate delivery of the Safe System as a road authority. The existing safety culture tools and models do not have the specificity of Safe System application and are unable to guide road safety organisations in the principles and actions required to adopt this best practice road safety approach. The SSCMM fills this gap.

A limitation of the SSCMM could be that, to date, it has only been tested on a small sample of organisations, all of whom are based in the UK. Further testing, and potential refinement, is required to determine its wider applicability. Working closely with organisations to implement cultural change programmes will test the effectiveness of Safe System implementation initiatives, and results of the sample analysis, alongside further testing will be published in future articles.

Another potential limitation is that there could be confounding factors which influence the application of Safe System interventions, including funding and political alignment. The model does not account for this but could be used to identify such factors, leading to further organisational investigations.

Conclusions

The Safe System Cultural Maturity Model proposed here is built from international guidance manuals and evidence across disciplines of road safety, cultural maturity, and organisational behaviour change. The actions included were categorised into change mechanisms, which were identified in Safe System models internationally.

The cultural maturity elements of the SSCMM are also based on an in-depth evidence review. The Hudson and Parker ‘Hearts and Minds’ model is familiar to many safety organisations, and it has been used in multiple safety contexts. For the SSCMM, the cultural maturity element is enhanced by the inclusion of the ISM model. This focus on the individual, social, and material maps well onto Safe System thinking as the choices of an organisation are based on the attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs of its individual members; the norms and values of the organisation; and the resources available to it.

The theoretical part of this study has resulted in a robust explanation of how cultural maturity can influence Safe System thinking and application. The aim, however, was to test whether cultural maturity could be diagnosed.

The purpose was to create a question set which could be diagnostic of an organisation; allows comparisons between organisations; can be used to evaluate progression or regression over time; and to support transformation of organisations in specific components, change mechanisms and/or actions. Initial testing has demonstrated that the tool provides this function and could be transformative in the way Safe System support is provided to road safety organisations.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Kate Honey at National Highways for commissioning the research and Dr Iain Rillie at National Highways for distributing the tool and processing and sharing the data. Thanks to all of the road safety stakeholders who participated in the survey tool test.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the study concept and design. MK and SS investigated the actions and models and all authors designed and reviewed the question set. TF acquired, processed, and analysed the test data. TF drafted the manuscript. DC created the visualizations. All authors were involved in interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by National Highways (England). National Highways supported the collection of data.

Human Research Ethics Review

Agilysis completes an internal Research Ethics Review (based on the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) checklist) for every research project to highlight risks and devise mitigation strategies. No risks were identified for this research.

Road safety experts who participated in the workshop were informed prior to the session that no personal data would be recorded, and no responses would be attributed to specific individuals. Informed consent was obtained verbally at the beginning of the session.

Respondents to the survey were not asked to supply any identifying information, with only role classification and organisation type for cultural maturity diagnoses. Respondents were informed at the start of the survey that their responses would remain anonymous.

Data availability statement

On request, the anonymised test data and question set are available. Details of the participating representatives and their organisations will be withheld as anonymity was assured.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper. Whilst funding for the work was provided by National Highways, the research methodology and results were not directed by the funding organisation.

.png)

.png)