Background

How do you get a community to care about road safety?

That was the underlying question addressed in this study. While the project focused on humanising cyclists, the underlying question is key to all road safety issues. In this paper we examine the steps taken to understanding and engaging a community in a road safety issue with the goal of improving road safety outcomes. The project was initiated by the Alpine Shire Council (the Council) who recognised the need for action to improve safety for cyclists on the road, specifically in shifting the culture among drivers to stop seeing cyclists as an impediment to their trip and instead as people. The Alpine Shire region is part of Northeast Victoria, where cycling tourism in the area is worth an estimated A$120 million per year. However, narrow, mountainous roads can make sharing the space challenging.

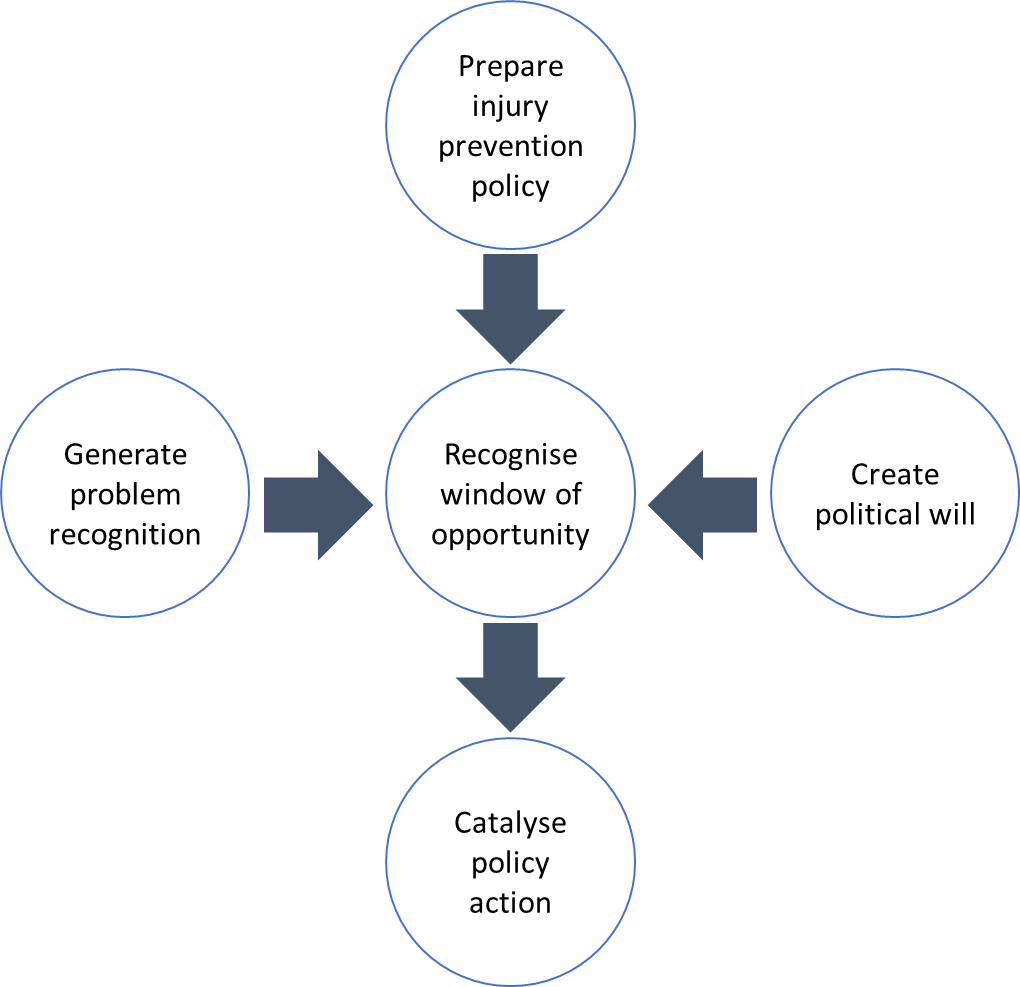

Our response was informed by the public policy approach developed by Bugeja et al (2011) (Figure 1). This approach recognises three ‘outside’ stages are needed to create a window of opportunity to catalyse policy action.

The Council had already taken steps towards addressing the three ‘outside’ stages, having been awarded a TAC Road Safety Community grant to implement a campaign. Our tasks were to test what had been proposed and maximise the road safety outcomes for the cyclists in the Alpine region. Below we present the project steps and how the theoretical model structured the project.

Generate problem recognition

The Council had identified the issue in their region was a poor relationship between drivers and cyclists on the roads, specifically, drivers who were tourists to the region, and cyclists who were a mix of local residents and visitors. The Council considered hostilities were exacerbated on popular tourist routes through the mountains by tourist drivers who were not familiar with the roads and impatient about being held up by slower moving cyclists. The understanding of the Council was residents in the Alpine Shire region were positive about cyclists on the road. This was based on their own cycling experience and the successful cycling tourism industry.

Prepare injury prevention policy

In their funding application, the solution proposed by the Council to create and launch a campaign that aimed to humanise cyclists, modelled the ‘Drive with care’ campaign from Bike PGH in the United States (Bike PGH, 2014). The campaign focused on ‘real people’ with a range of jobs, responsibilities and positioned them in their family with the tagline, ‘Rides a bike’. Given it was almost ten years since the US campaign, the Council acknowledged a static, print-based campaign would not have the cut-through it once did. The new campaign would need to also include a video version of the campaign given the support from the local cinema in Bright. The working title for the campaign from the Council was Ride like a local.

Create political will

Political will is a critical and often most difficult step to achieve, including in road safety. The challenge is to persuade decision makers to act according to the science which might be at odds with what is considered politically palatable. However, in this project, this was not a factor as the Council had internal support for the project.

Recognise window of opportunity

Funding from the TAC provided the window of opportunity and the Council put the project out to tender. As a starting point, this seems straightforward, the next step being to develop a campaign using local people, targeting tourist drivers. However, our team has extensive cyclist safety research and campaign experience and we were aware of some red flags: 1) the budget, $20,000 was too small for this project. It could cost the entire budget on the campaign alone; 2) there was no provision to test the veracity of the problem, that is – were tourist drivers really the problem? 3) how would they know it worked? How would the campaign be evaluated?

Given our collective passion for cyclist safety and this rare window of opportunity, we called the Council to offer our expertise and share our concerns. We wanted to help make sure that regardless of who was awarded the project, the best outcome was delivered. We offered our support in whatever capacity would best help the Council, for example, reviewing applications and providing a steering committee throughout the project. Following these early discussions, the Council invited us to bid for the project, which we did and included our caveats about the project scope.

We were awarded the project in June 2020. Given all the background work done by the Council, it would make sense to jump into the next step, ‘Catalyse policy action’, and start creating the campaign. But based on our road safety knowledge, we knew we needed to go back to the problem generation stage and make sure targeting tourist drivers was the right approach.

The aim in this study was to develop an evidence-based campaign that engaged the community and contributed to humanising cyclists on the road.

Setting – Alpine Shire region

The project was conducted in the Alpine Shire region approximately 320 kilometres north-east of Melbourne, Victoria. The region, also known as the Victorian high country is largely national parks with popular ski fields and mountain biking. In 2019, over half a million people stayed overnight as tourists to the Alpine shire with three quarters (74.8%) visiting on holiday (Alpine Shire Council, 2022).

It was important to understanding that although the resident community is small (13,200), there is not one homogenous ‘Alpine Shire’. Residents felt affiliated with their area and township (e.g., Bright, Mt Beauty, Myrtleford) and the region contained a number of communities in different geographic areas within the shire. Tourists were considered a separate category with distinct differences in attitudes and behaviours compared to residents. The Council were clear that while Bright is the largest township in the region (19% of the population), it is an oversimplification to equate Alpine with Bright and a campaign needed to include the whole region.

Method

Our starting point was to test the Council’s assumptions that local people were positive about cyclists and the campaign needed to target visiting drivers. We planned the project in four stages: 1) key stakeholder engagement, 2) community consultation including local residents and tourists, 3) campaign creation and delivery and 4) evaluation. Originally, stages 1 and the local resident part of stage 2 were to be in-person, however, we needed to adapt in response to the disruptions of COVID-19 (COVID). Discussed below are the practical approaches we used to manage the project during the disruptions and the modified study design.

Managing a COVID-disrupted project – practical approach

Similar to almost everything in the world, this project was impacted by COVID. Most significantly on 9 July 2020, when the Victorian Government implemented a ‘ring of steel’ around metropolitan Melbourne (Stage 4 lockdown). The ‘ring of steel’ was a government restriction that prohibited travel between metropolitan Melbourne and the rest of the state. Police enforced the measure stopping all drivers, and this research study did not meet the criteria for approved travel. All the researchers lived in Melbourne and were prohibited from travelling to regional Victoria. Any in-person consultation and engagement were not possible and the project required modification.

Inception meeting: COVID meant that we were unable to meet in person so we moved to online. The inception meeting included the researchers (MJ, RN, VJ) and representatives from the project partners (Alpine Shire, Amy Gillett Foundation). Typically, a project inception meeting would involve the researchers and one representative from the partners but we took advantage of meeting online to invite everyone who would be involved in the project (communication, tourism, marketing, administration, accounting, management). Having everyone in the inception meeting ensured everyone understood the aims of the project and the potential challenges.

Simple tools to staying on track: our first simple tool was weekly meetings for the duration of the project (Thursdays, 9-10am) to maintain momentum and help with accountability and transparency. We provided our project partners with regular updates and invited them to join us at regular intervals (four-six weeks). We used the same online meeting link for the entire project to minimise the hassle of finding the ‘right’ link. The meeting frequency may seem excessive; however, weekly meetings were critical to maintaining momentum and focus.

Our second simple tool was a shared, detailed Gantt chart in Google Sheets. The breakdown of tasks by project stage became our agenda to structure meetings, track progress and identify concerns for discussion. The document was shared with the entire team, including the partners. We built on the document with additional sheets to track details of the project (e.g., budget, communications strategy, stakeholder contact details, survey questions, prize winners etc). This document became the single source of information, available to everyone and updated live; it streamlined our processes and eliminated confusion (e.g., version control).

Modified timeline: In consultation with the Council, we repeatedly delayed in-person research stages in response to COVID restrictions. This was both the practical government sanctions and in response to the sentiment in regional areas and reported antagonism about people from Melbourne, where there were more active cases of COVID, visiting regional Victoria. In addition, the Council advised lockdowns were limiting tourism and they observed fewer people riding and driving on the roads. It was assumed this may affect drivers’ experiences and alter perceptions about sharing the roads.

Following further delays due to lockdowns, we abandoned the in-person stage in August 2020. On reflection, this was the correct decision. The ‘ring of steel’ continued for four months and would have made it impossible to deliver the project in the original format in an acceptable time period.

The final modified approach kept the four stages but shifted Stages 1 and 2 to online. The study protocol was approved by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (Approval number 2021/25152-55794) including all modifications (MJ, RN) and RMIT University HREC (VJ).

Modified Method and Results

Stakeholder engagement

In consultation with the Council, we identified 53 key stakeholders at individual and/or organisational levels, across business, community and civic sectors that operated in the Alpine, including:

-

Accommodation (e.g., caravan parks)

-

Alpine Shire Council

-

Cycling related businesses

-

Department of Transport

-

Health care

-

Local cycling clubs

-

Local retailers (e.g., coffee shops, brewery)

-

Representative organisations (e.g., Chamber of Commerce)

-

Schools

-

Social, community (e.g., Rotary, Country Women’s Association)

-

State parks (e.g., Mt Buffalo Park)

-

Tourism

-

Trucking companies active in Alpine

-

Victoria Police

Stakeholders were invited to participate in one of two one-hour online focus groups (Thursday 20 August 2020, n=7; Wednesday 26 August 2020, n=9). Participants were from local council, local businesses (Bright, Mt Beauty), cycling related businesses, schools (primary), health care, social and community groups, Victoria Police and tourism.

Both groups followed the same schedule that started with a welcome and introduction, semi-structured discussion of four topics (below) and closed with next steps.

-

Concerns about drivers and cyclists sharing the roads in the Alpine Shire region including residents, visitors, specific locations

-

Attitudes and culture about key factors in perceptions about cyclists and perceptions of drivers/vehicle types

-

Road rules, behaviour and infrastructure: understanding of how road rules contribute to behaviour on the roads. Advice about sharing the roads and the role of infrastructure

-

Suggestions to improve road safety

There were three key roles for the researchers during the focus groups: topic chair, note taker and time keeper. These roles were allocated according to each researcher’s expertise. All focus groups were recorded and we typed notes directly into a live GoogleDoc visible to all researchers that allowed us to capture key comments and assist the topic chair by providing live feedback and discussion prompts.

In addition to the focus groups, the discussion topics were emailed to all 53 invited participants, inviting any additional comments or insights. Feedback was received from 5 stakeholders who did not attend the focus groups. From the analysis of the focus groups and the additional feedback, five key areas were identified: concerns, attitudes, road rules, infrastructure and behaviour. These findings informed the survey that was developed for the community consultation stage.

Community consultation

Following COVID disruptions, the community engagement stage was also moved online. Informed by insights from the stakeholder focus groups, the researchers developed an online survey (Survey 1). Questions also asked about content for the video campaign, in particular gestures or actions already used on the roads that could be utilised in the campaign to address the overarching project aim, to humanise cyclists. We invited feedback on Survey 1 questions from the Council, Amy Gillett Foundation and two key stakeholders: Tourism North East (TNE), and Ride High Country (RHC). TNE and RHC were integral in identifying popular cycling routes in the area.

The survey was developed and published on Qualtrics XM Platform, hosted by Monash University. The survey was open for one month from 15 September 2020 then on request from the Council, extended to 1 November 2020. The survey was open to people who were residents or visitors to the Alpine area.

Recruitment

According to the original Council tender, a minimum sample size of 200 people was required in the community engagement. To meet this requirement, we recruited survey participants through a variety of channels, including social media (Amy Gillett Foundation, Alpine Shire Council), the researchers’ professional networks and social networking platforms (e.g., LinkedIn, Facebook) (Figure 2). In addition, a popular cycling event, the Alpine Classic, was scheduled for late January 2021. We liaised with the organisers of the event, O2, who sent the survey link to be sent to all event participants.

Incentives

Surveys were used in Stage 2 (community engagement) and Stage 4 (campaign evaluation) and both included an incentive prize draw. For each survey, the Council provided three ‘Buy from Bright’ vouchers valued at $100 each. To be eligible, participants needed to submit a completed survey and opt-in. Winners were selected at random, notified by email and their first name and first initial of their surname were published in the summary of results (Figure 3).

Results

In total, 569 completed survey responses were received for Survey 1 including from local residents (n=310, 54.4%) and visitors (from Victoria, n=212, 37.3%; outside Victoria, n=47, 8.3%).

All responses were analysed to identify the key concerns about sharing the roads with cyclists including the perspectives of people who both cycled and drove as well as people who did not cycle. A key finding was how road users (drivers and riders) communicate to each other in the Alpine Shire. Responses identified an ‘Alpine wave’ consisting of a whole hand, raised finger or fingers, as a common form of communication among Alpine locals, and visitors to the Alpine Shire. Anecdotally, we recognised this as a common greeting in other parts of Australia. We determined a ‘wave’ should be a key feature in the campaign and support other messages around humanising cyclists and sharing the road from both residents and visitors. Figure 3 is the summary of key results, as provided to participants. Also, in the survey we invited people to be part of the campaign.

Testing assumptions

Key findings from the stakeholder focus groups and the community consultation challenged the assumptions made by the Council that negative attitudes towards cyclists were mainly from tourists. Both positive and negative comments were made in both stages by all groups including key stakeholders, local residents and tourists. Common negative points made were the legitimacy of cyclists as road users (i.e., roads are for cars, not bikes), the perceived value of trips (i.e., drivers’ trip purposes are of value while cyclists only ride for pleasure) and cyclists should only ride off road. The most hostile comments were made online by local residents in individual responses to Facebook posts made by the Council.

Testing the assumptions was an essential component of this study and provided a solid evidence base for the creative campaign. It was clear from the first two stages that the focus of the campaign was not just visiting drivers but also local residents, both as drivers and as cyclists.

Campaign creation and delivery

The original project plan for the campaign included: road signage, print collateral for distribution, social media messaging, print media, video and radio. Production, originally scheduled for September 2020, was abandoned due to extensive delays due to COVID lockdowns. There was also the foreseeable risk of additional costs (i.e., quarantine). To mitigate these risks, we abandoned the video component in consultation with the Council. In October 2020, we engaged creative agency DGB Group to develop the print/digital elements. However, when lockdown restrictions were lifted in November 2020, we were able reinstate the video and we continued the campaign development to include the video with DGB Group.

Development of the campaign – Live, Drive, Ride like a Local

The researchers collaborated with DGB Group to translate key research findings into a creative campaign. Similar to the USA campaign, it would feature a range of people and include the new video component. To address the hostility towards cyclists identified in Stages 1 and 2 and to acknowledge that cyclists were also drivers who lived in the area, the tagline evolved to ‘Live, Drive, Ride Like a Local’. The approach was then storyboarded by DGB Group in collaboration with the researchers. Researchers scouted filming locations throughout the Alpine region in late December 2020. Researchers and DGB crew travelled to the Alpine Shire to film, photograph and interview residents and film location shots on 5-8 January 2021.

Local residents who were featured in the campaign were identified because they had volunteered in their response to Survey 1 or were recommended by Council. In total, 11 residents were photographed and videoed cycling, driving or walking in the Alpine Shire. Nine participants were interviewed about their experiences cycling in the Alpine Shire area (two people were not included due to scheduling constraints). Editing and post-production work were completed in the week starting 18 January 2021. The campaign consisted of a series of complementary education and awareness outputs in both print and video/digital formats involving:

-

Alpine Shire residents (e.g., teachers, local business people)

-

images or activities of residents in their regular/work clothes, and cycling (sporting/lycra or casual) clothes

-

road safety messages with residents’ stories about sharing the road as a rider and a driver

The campaign was designed for print, digital and video and collateral included:

-

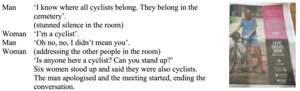

full page colour ad in local newspaper (The Alpine Observer and Myrtleford Times)

-

finish line gantry for the Alpine Classic cycling event featuring six participants

-

A1 and A3 posters were created for each individual participant, featuring the ‘Live Drive Ride like a Local’ message, plus a quotation to accompany the individual’s photograph (Figure 4)

-

A5 postcards were created for each individual participant, featuring the ‘Live Drive Ride like a Local’ message, plus a quotation to accompany the individual’s photograph

-

metal stencil to allow Live, Drive, Ride like a Local to be spray painted on local surfaces (e.g. on the road)

Video

-

short film (3 minutes) (Figure 5)

-

clips of residents telling their stories (30-90 secs for social media, cinema, television)

Targeted distribution was achieved using the Council’s social media pages, geofenced posts to the Alpine region from the Amy Gillett Foundation and distribution by O2 to all event participants.

Project Implementation and Delivery

The campaign was launched at the Alpine Classic cycling event in Bright on 23-24 January 2021. This public launch, held on the public space in the centre of town, was attended by over 200 people including the featured campaign participants, their families and friends. The original project plan also included radio content, however, this could not be completed due to the time constraints. All original interview audio was provided to the Council for their use.

Reach and engagement

In total there were 34 social media posts from September 2020 to April 2021. These posts included survey recruitment and campaign dissemination including the full length video, a short ‘meet the people’ cut (1 minute) and print images of all the people featured in the campaign. Almost 90,000 points of contact were reported for the social media posts (Table 1).

Campaign video

The full video has been viewed over 4,800 times on YouTube (over 1,200) and the Amy Gillett Foundation Facebook (over 3,600). Note these are likely underestimates as the video posts were shared (AGF: 31; Alpine Shire: 1) and metrics are not available for shared posts views.

In addition, Monash University media wrote and published a news article on their website (Figure 6). This was republished across ten outlets including mainstream media (e.g., The Sunday Herald Sun (print)) and online (e.g., www.eglobaltravelmedia.com.au). Summary data from Monash Media reports a reach of almost 1 million views with an advertising equivalent of $8,622.

Importantly, data from the Monash University article included a sentiment rating of how the reposted article framed the content piece. Sentiment was mainly positive (80%) or neutral (20%).

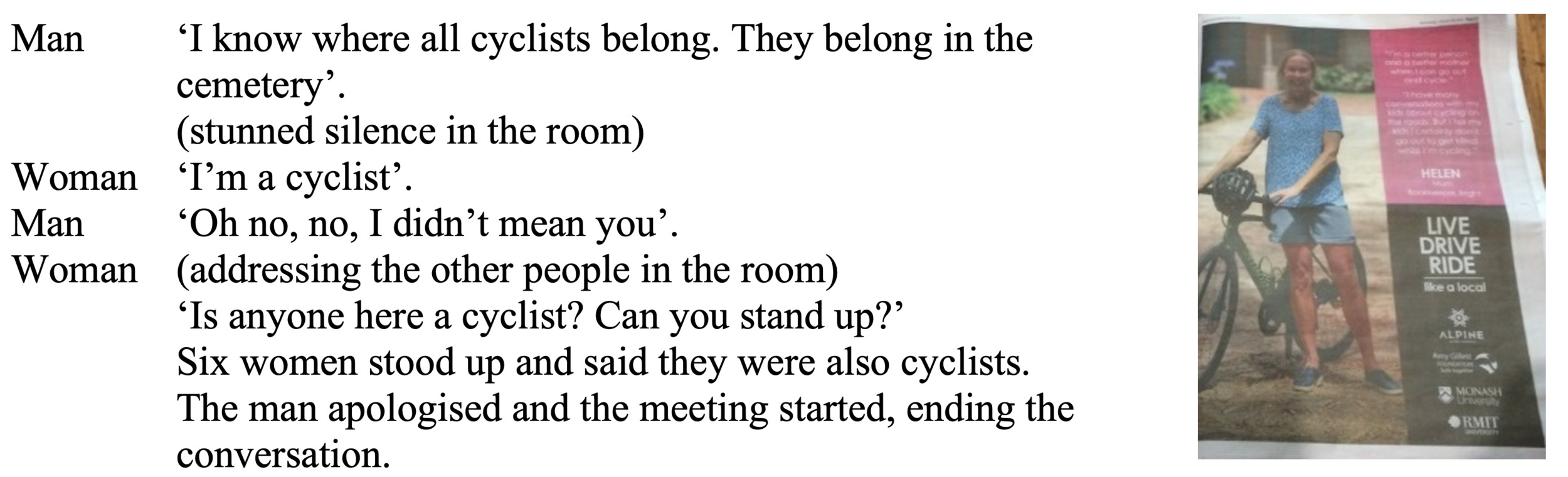

Impact – community conversations

We received feedback about an interaction that occurred in response to the campaign. A woman, a resident from Bright, attended a community meeting the night the campaign image was published in the local paper. Before the meeting, people were chatting about the campaign and making general comments about cyclists when the following conversation occurred.

The man’s comment is concerning, both the content and that he felt comfortable making it publicly. The positive outcome was due to the woman’s response and could easily have deteriorated into an argument. While he may have intended to be flippant or humorous, it may indicate deeper anti-cyclist sentiment from some residents in the Alpine community.

Evaluation

Two months post-campaign, an online survey was conducted to evaluate the campaign effectiveness (print and digital versions) in terms of empathy for road users, knowledge of road rules and understanding of safe, shared road use (Survey 2). The Council and Amy Gillett Foundation provided feedback to draft questions. Timing of the evaluation was in consultation with Council to allow time for distribution of the campaign collateral via their social media platforms.

As for Survey 1, the final survey tool for Survey 2 was published on Qualtrics XM Platform hosted by Monash University. It was open from 16 March to 25 April 2021 to people living in the Alpine area and visitors. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse survey responses.

Recruitment

Invitations to respond to Survey 2 were made via social media platforms. As for Survey 1, the survey was open to all interested people who lived in or visited the Alpine Shire. Also, the Survey 2 link was emailed to all Survey 1 respondents who had agreed to participate in the evaluation.

Results

Evaluation survey responses (n=97) reported positive reactions. After watching the video, the top two unprompted key messages were: people riding bikes are normal people (34%) and mutual respect is needed when sharing the road (27%) with most people (92%) agreeing that more education of drivers and cyclists is needed. Most respondents wanted campaigns to include the local area (91%) and local residents (82%) rather than social influencers (51%) or celebrities (48%).

In comparison to the response to Survey 1, 97 responses for the evaluation is comparatively low. We used social media to recruit for both surveys through project partners (Amy Gillett Foundation, the Council), however we did not have the additional post to cycling event participants that was available for survey 1. It is likely this played a role in the lower recruitment rate.

Conclusion

The success of this project was in large part due to the strong relationships built with the Council staff through regular communication and a shared willingness to try new and innovative approaches. The travel disruptions, particularly the ring of steel, due to COVID caused substantial disruptions to this project. Trust between the Council and the researchers that we were all working towards the same goal gave us the flexibility to deliver a successful project that engaged the local community.

This project successfully engaged a local community to humanise cyclists, specifically by identifying cyclists as local people. The project provides important insights about the type of content that engages local communities and will help to inform future campaigns.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the broader team that contributed to the development and creation of this project and the Live, Drive, Ride like a Local campaign: from the Amy Gillett Foundation, Sarah Dalton and Carly Bisko; from the DGB Group, Craig Blanchard, Adam Bostock and Jude Manussen. We also thank all the respondents to the surveys and residents and business owners in the Alpine region who supported this project. Special thanks to the eleven campaign participants: Cooper, Daniel, David, Doug, Fiona, Helen, Mark, Megan, Nick, Phil and Sam and their families for their time and generosity in contributing to this project. Their experiences and stories were fundamental to us being able to present a humanised view of cyclists in the Alpine region.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, design, execution, analysis and interpretation of this project. Johnson led the manuscript preparation and writing with contributions from Napper, Johnston and Corser. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Alpine Shire Council through a Transport Accident Commission (TAC) Community Road Safety Grant. With additional funds from the Amy Gillett Foundation and Monash University. In-kind support was also provided by Monash University, RMIT University and the Amy Gillett Foundation.

Human Research Ethics Review

The Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) was the lead committee and approved all stages of this project and were updated and provided additional approval to the modified stages. Monash University HREC approval reference number 2021/25152-55794. Application was made to the RMIT University HREC that recognised the approval from Monash University. Again, updates for the modified stages were provided and recognised by RMIT University.

Data availability statement

Data and materials are available on request.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

.jpg)

.jpg)