Introduction

Road traffic crashes (RTC) are crashes that occur on a way or a street open to public traffic, resulting in one or more persons being injured or killed, and at least one moving vehicle being involved. RTC includes crashes between vehicles, vehicles and pedestrians, vehicles and animals, or fixed obstacles (OECD, 2020). It is a major but neglected public health problem that requires concerted efforts for effective and sustainable prevention (Sleet et al., 2011).

RTC have become a global public health problem, killing over 1.35 million people in a year and disabling 50 million others. According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) global status report(2018), RTC was the eighth leading cause of death for all age groups, killing more people than HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and diarrheal diseases. More importantly, it is a leading cause of death among children and young adults aged 5-29 years, posing a new threat to the health of adolescents and working-age populations. RTC also result in a huge economic burden, with an estimated loss of nearly two trillion USD to the world economy in 2015-30. In addition, perceived poor road safety also impacts other public health issues as it contributes to physical inactivity and stress. People are less likely to walk or cycle when road conditions are unsafe (WHO, 2018; Chen et al., 2019).

Even though RTC are global challenges, they are more severe in low and middle-income countries (LMIC), where 90 percent of the world’s crash deaths occur. The annual RTC death rate in LMIC is three times higher than the death rate in high-income countries. The African region has the highest rate of fatalities from RTC worldwide. What is more, there has been no reduction in the number of road traffic fatalities in any low-income country since 2013 (WHO, 2018).

In Ethiopia, RTC constitute a major burden on the social, economic, and health sectors. According to the WHO report, Ethiopia is considered one of the worst-affected countries in the world, where RTC causes an estimated annual death of over 27,326 people (WHO, 2018; UNEC, 2020; WHO, 2014). According to the official government reports, annual RTC deaths have doubled in the 12-year period between 2007 and 2018 (UNEC, 2019) RTC are the ninth leading cause of death in Ethiopia; the country is ranked 12th in the world, and 9th in Africa in terms of deaths and injuries caused by this public health problem (WHO, 2013). In addition to the direct morbidity and mortality, RTC also adversely affect the livelihoods of individuals and families often forcing them into poverty (Kussia, 2017; Persson, 2008). It has a huge impact on the national economy by consuming already scarce health resources, damaging properties, and killing or disabling the working-age group (Mekonnen & Teshager, 2014).

Several factors predict the occurrence of RTC. Driver factors are the most common ones. Most global and local initiatives are also directed towards the five most common risky driving behaviours: speeding, drink driving, inconsistent use of seatbelts, helmet use, and poor utilisation of child restraint systems (Hareru et al., 2022; Nabi et al., 2005; Neelakantan et al., 2017). Despite this, few studies have been conducted on drivers in Ethiopia.

In addition, in Ethiopia, there is a shortage of reliable data and research-based recommendations, especially those conducted using robust epidemiologic designs (UNEC, 2020). A few studies attempted to capture the problem, but they used study designs and techniques that were not robust enough to address it. Most studies used descriptive techniques, and some failed to collect first-hand information from the drivers (Abegaz et al., 2014; Honelgn & Wuletaw, 2020; Mekonnen & Teshager, 2014). A study conducted in Western Ethiopia used a cross-sectional design, which is not as reliable as case-control studies in identifying determinants (Erena & Heyi, 2020). Two national studies collected the information out of the primary stakeholders in the RTC. Even though these studies involved relatively large sample sizes, they significantly diverted from primary stakeholders, which may underestimate the problem (Abegaz & Gebremedhin, 2019; Gebremichael et al., 2017). The current study was conducted to identify the determinants of RTC using firsthand information from the drivers and a relatively robust epidemiologic study design.

Methods

Study area, design and period

This study was conducted in the Buno Bedelle zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Buno Bedelle is one of the administrative zones of the Oromia region, the widest and most populous region in Ethiopia. As of 2021, the zone had a total population of 829,663. Bedelle town is the capital of the Buno Bedelle zone, 480 km away from Addis Ababa, the national capital. The transport system in the zone is managed by the zonal transport authority. In 2021, in the Buno Bedelle zone, there was 2,441 registered drivers and 1,921 different types of vehicles, 145 km of paved asphalt roads and 903 km of gravel roads. The study was conducted from May to July 2021, employing a community-based unmatched case-control study design.

Study populations

The study populations for cases were drivers registered in the zonal traffic police office as causing crashes over one year prior to the data collection period and fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The study populations for controls were drivers who had not caused a RTC as identified by the zonal transport authority in the year preceding the study and sampled after fulfilling the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Cases: registered drivers who had RTC in the year preceding the study, survived the incident, and registered as having caused the RTC in the zonal transport authority; with address information available from the zonal registry.

Controls: registered drivers who had been driving for a minimum duration of 30 days in the year preceding the data collection period, who did not inflict or cause a RTC, with address information is available from the zonal registry.

Exclusion criteria

Cases: registered drivers who are critically ill or died due to any disease after the incident; those who have changed their residence since the last RTC; missing address information.

Controls: registered drivers who were critically ill, died, changed residence, or inflicted RTC after the initiation of the study.

Sample size determination and sampling procedures

The sample size was calculated using STATCALC of epi-info-7, considering a case-to-control ratio of 1:2, a power of 80 percent, and a two-sided confidence interval of 95 percent. The sample size was calculated for key behavioural risk factors for RTC. Finally, mobile phone use while driving was chosen as it resulted in the largest sample size using an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 2.25, the proportion of exposed controls as 17.3 percent, and the proportion of exposed cases as 32.3 percent (Woldu et al., 2020). This resulted in a sample size of 103 for cases and 205 for controls. After adding 10 percent for the non-response rate, the required sample size was 113 cases and 226 controls, giving a total sample size of 339.

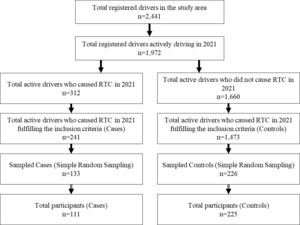

A complete list of drivers who inflicted or caused RTC (cases) and did not inflict RTC over the year prior to the study period (controls) was taken from the register book of the zonal transport authority. Essential address and contact information were collected from the register. The list was refined by applying inclusion and exclusion criteria. Cases and controls were selected separately by simple random sampling from the list. Selected drivers, both cases and controls, were reached according to the contact and address information from the register (Figure 1).

Operational definitions

Road Traffic Crash: a crash that involves personal or property injury occurs on roads (including footways), involving at least one vehicle or a vehicle in crash with a pedestrian, another vehicle, or other object and which becomes known to the police within 30 days and is registered to have happened on the authority register book (Honelgn & Wuletaw, 2020; Odero et al., 1997; Tiruneh et al., 2014).

Distracted driving: anything that takes the attention of the driver away from driving, like texting, talking on a cell phone, using social media, and eating while driving (NHTSA, 2018; CDC, 2017).

Data collection tools and procedures

The data were collected using a pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire. The English version of the questionnaire was translated into the local language (Afaan Oromo). Eight trained clinical nurses collected the data under the supervision of two senior health officers. The data were collected according to the suitability of time for the drivers on weekends, at meeting sites, and at bus stations. Transport authority workers facilitated communication between the data collectors and selected drivers.

Data processing and analysis

Data were entered into Epidata version 3.1 and exported to the statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 23 for analysis. Relevant descriptive statistics were used to describe variables according to their distribution. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify independent determinants of RTC by using the OR and its 95 percent confidence interval (CI) at p < 0.05.

Ethical Consideration

This research was conducted according to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Ethical approval for the conduct of the study was obtained from the ethics review committee of the college of health science at Mattu University with reference number RPG/18/2013, issued on 11 May 2021. Permission was obtained from the Buno Bedele Zone Health Department, the Transport Authority, and the Police Department. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants after a detailed explanation of the purpose, objectives, risks, and benefits of the study.

Patient and public involvement

The public was involved from the initial design of data collection tools through pretesting. This helped in aligning the questions in the data collection tool to make them appropriate and acceptable to the study participants. The potential participants were consulted on the appropriate times and locations for data collection. Finally, plans were put in place with study participants to disseminate the results of this study.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

From the total sample size, 336 study participants responded to the questionnaires (99.1% response rate). The respondents included cases (n=111, 33%) and controls (n=225, 67%). All of the cases and 224 (99.6%) of the controls were male. The majority of respondents were in the age group of 25 to 34 years (cases, n=65.8% controls, n=69.8%). Regarding marital status, more cases were single (60.6%) compared to controls (49.8%). Concerning the ethnicity of respondents, most of the cases (69.4%) and controls (85.3%) were ethnic Oromo. Most of the participants had completed secondary school (cases, 78.4%; controls, 75.1%) (Table 1).

Characteristics of respondents and their immediate environment

In this study, 81 (73%) cases and 116 (51.6%) controls had fewer than five years of driving experience. However, seatbelt use was inconsistent as most cases (74.8%) and some controls (40%), did not use seatbelts consistently. More than half of cases and two thirds of controls (65.8%) of controls reported chewing khat (stimulant) while driving. Meanwhile, 54.1 percent of cases and 78.2 percent of controls overloaded, driving with more than the permitted number of people in the vehicle. Regarding the ownership of vehicles, the majority of cases (86.5%) and controls (80.4%) were employed drivers. Moreover, approximately half of cases (55%) and controls (46.7%) drove on gravel roads routinely. Furthermore, 57.7 percent of cases and 40 percent of controls reported driving for more than eight hours per day (Table 2).

Determinants of road traffic crashes among drivers in Buno Bedele zone

Predictor variables were entered into the binary logistic regression model to identify important variables for the multivariable model. Monthly income of drivers, inconsistent use of seatbelts while driving, having children, years of driving experience, driving under the influence of alcohol, driving under the influence of khat, overloading passengers, vehicle ownership, average driving hours, music listening while driving, road pavement, vehicle inspection interval, speeding and vehicle length of service were found to have p-values of <0.25 and were included in the multivariate analysis (Table 3).

In the multivariable model, years of driving experience, inconsistent use of seatbelts, driving under the influence of alcohol, vehicle length of service and speeding were significantly associated with road traffic crashes among drivers in the study area. Drivers with fewer than five years driving experience were almost three times more likely to inflict RTC than experienced drivers (OR = 2.6, 95% CI (1.04, 6.3)). In relation to seat belt utilisation, inconsistent users of seatbelts were three times more likely to inflict RTC than drivers who used seatbelts consistently (OR = 3.2, 95% CI (1.6, 6.3)). This study also found drivers who were under the influence of alcohol to be five times more likely to inflict crashes than drivers free of alcohol influence (OR = 5.2, 95% CI (2.3, 11.7)). In addition, drivers who drive vehicles older than five years were nearly three times more likely to inflict RTC than drivers of newer vehicles (OR = 2.6, 95% CI (1.3, 5.3)). Finally, speeding was found to be significantly associated with RTC. Drivers who drive over the speed limit were nearly five times more likely to cause RTC when compared with drivers who observed speed limits while driving (Table 4).

Discussion

This community-based case-control study has identified the determinants of RTC among drivers in the Buno Bedelle zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Accordingly, the current study found short years of driving experience, inconsistent use of seatbelts, driving under the influence of alcohol, long vehicle length of service and speeding to be significantly associated with RTC among drivers in the study area.

Short driving experience was found to be independently associated with RTC in the study area. Drivers with fewer years of driving experience were two times more likely to cause or inflict RTC than drivers with more years of driving experience. This finding has strengthened the claims of descriptive studies conducted in Northern Ethiopia (Tadege, 2020; Woldu et al., 2020), which associated experienced drivers with a lower probability of risky driving behaviours. This is also in line with a finding from Benin City, Nigeria, which found less experienced drivers inflicting more RTC than experienced drivers (Okafor et al., 2017). Findings from research conducted in countries of all development levels indicated a relationship between a lack of sufficient driving experience and risky driving behaviours (Mekonnen et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2021; Madhumali et al., 2021). The occurrence of risky driving behaviours is associated with a greater likelihood of the occurrence of RTC (WHO, 2018).

Likewise, this study revealed inconsistent use of seatbelts as being significantly associated with RTC. Inconsistent users of seatbelts inflicted RTC three times more than drivers who used seatbelts consistently. This corroborated the findings of other studies conducted in Northern Ethiopia and Thailand (Fenta & Muluneh, 2017; Klinjun et al., 2021). One of the most important behaviours that is a proxy indicator of the prevention of RTC is the use of seatbelts (WHO, 2018). It helps in the prevention of injuries and reduces their severity (Fouda Mbarga et al., 2018). This study indicated the continuing importance of seatbelt utilisation in the prevention of RTC.

Driving under the influence of alcohol is found to be a strongly associated with RTC. Drivers who drove after consuming alcohol were five times more likely to inflict RTC compared with drivers who did not consume alcohol. The current finding supports available knowledge concerning the impact of alcohol on road and traffic safety. In addition, it supports prior findings from studies in Ethiopia and elsewhere (Hı́jar et al., 2000; Tiruneh et al., 2014; Woldu et al., 2020). This study has shown the continued risk and threat posed by drink drivers to Ethiopian road users.

In this study, drivers who drive older motor vehicles are twice as likely to inflict RTC than drivers of newer vehicles. This is consistent with a study conducted in Addis Ababa (Mengistu & Enquselassie, 2021). This might be due to older vehicles developing defects of different origins that may make it difficult to manage them when threats to road safety arise. This finding is inconsistent with a report from a study conducted in North Ethiopia, which stated that, as vehicle service years increase by a year, the probability of the occurrence of RTC decreases by 0.90 times (Tadege, 2020). This may be due to the relationship between vehicles and drivers in that, when the vehicle is new, the driver may not know the characteristics of the vehicle.

Finally, drivers who drive over the speed limit were found to be associated with nearly five times more RTC when compared with drivers who consistently observe the speed limits. Speeding is one of the five risky driving practices (WHO, 2018). Several studies also indicated the importance of speeding in causing RTC and worsening its consequences (Yasmeen, 2019; Yismaw & Ahmed, 2015).

Generally, the finding of this study implies the importance of improving the driving experience of future drivers by implementation of a mentored driving schedule before licensure. In addition, Ethiopia has to strengthen the implementation of the available legislations on risky driving practices by reforming, empowering and funding the road safety agencies. Finally, Ethiopia has to impose a limitation on the import of older motor vehicles. These recommendations all support the road safety performance review on Ethiopia, conducted by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNEC, 2020).

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study is the first of its kind to employ a case-control study in the study of road traffic crashes in Ethiopia. Despite this, the study has some limitations. Road traffic crashes that may have happened but did not come to the attention of the transport authorities and were not registered were not included in this study (underreporting). In addition, the data were collected on past events, and recall bias may have occurred. Further, the study focused on drivers and their immediate environment but did not consider other perspectives like infrastructure, other road users, or administrative issues.

Conclusions

In conclusion, factors associated with inflicting RTC among drivers in the study area are found to be a lack of sufficient driving experience, inconsistent seat belt utilisation, driving under the influence of alcohol, and long vehicle years of service. It is recommended that drivers develop their driving experience by driving under supervision before starting to drive independently. In addition, drivers are advised to avoid risky driving behaviours and abide by existing laws regarding risky driving behaviours. Transport service users are advised to look for experienced drivers and relatively new vehicles, drivers who constantly use seatbelts while driving, and recognised drivers who are known for their healthy driving behaviours. Transport authorities are advised to implement licensing procedures that require a longer period of supervised driving. Enforcement of existing laws concerning risky driving practises should be strengthened. The use of available technology in alcohol detection has to be strengthened. Authorities can also establish a grading system for drivers depending on their achievements regarding risky driving behaviours.

Human Research Ethics Review

This research was conducted according to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. The proposal for this study was approved by the ethics review committee of the college of health science at Mattu University, with letter reference number RPG/18/2013 issued on 3 May 2013 on the Ethiopian calendar. Individual participants provided written informed consent after receiving comprehensive information about the purpose, objectives, risks, and benefits of the study.

Data availability statement

All data for this research are available and can be accessed from the corresponding author.

Conflict of interests

All authors declare that there is no competing interest.