Glossary

AIP Alcohol interlock program

AUDIT Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

BAC Blood alcohol content

Introduction

Since the 1980s, many countries have experienced large reductions in alcohol-impaired driving (Robertson, Valentine, et al., 2018), amounting to approximately 50 percent in Great Britain, 39 percent in France, 37 percent in Germany, 32 percent in Australia, 28 percent in Canada and The Netherlands, and 26 percent in the United States (US) (Sweedler et al., 2004). However, since the early 1990s, the rate of drinking and driving and the decline in serious road crash injuries that are alcohol-related appears to have plateaued at approximately 10 percent on average globally (the absolute amount varies considerably from country to country) (Vissers et al., 2017). This suggests that it is important to consider mechanisms other than just education, enforcement, and licence disqualification to mitigate drink driving risk. Jurisdictions around the world have trialled and implemented Alcohol Interlock Programs (AIP) in an attempt to reduce this residual and persistent level of alcohol-impaired driving.

Alcohol interlocks are devices that are installed in a motor vehicle to create a technological barrier to starting the motor vehicle when a potential driver is alcohol-impaired (Marques, 2005). The device requires the driver to provide a breath sample, which is then analysed by the device, only allowing the vehicle to start if the sample reading is below a pre-set blood alcohol content (BAC) level. The device collects a variety of information, including attempts to start the vehicle while above the pre-set BAC level, results of samples collected during the journey (rolling retest), any attempt to disconnect the device, and the date and time of these events (Marques & Voas, 2010). Alcohol interlocks are available for purchase for private use and also have potential as a preventative fleet safety measure to tackle drink driving (e.g., see Fitzharris et al., 2015; Robertson & Vanlaar, 2014).

The purpose of AIP is to separate drinking and driving behaviour. In their simplest form, they are designed to prevent drivers convicted of drink driving offences from continuing to drive when they affected by alcohol. More sophisticated programs also contain ongoing monitoring, often with a requirement that the separation of drinking and driving is demonstrated for a specified period. This requires the return to an authorised service centre regularly for inspection, calibration checks, and downloading of the interlock data. Typically, the cost of the interlock and associated requirements is borne by the driver, although many programs have provision for some form of financial assistance for those judged unable to meet these costs (Filtness et al., 2015). Some programs also contain an assessment and treatment component aimed at bolstering compliance and reducing recidivism once the program is completed (Marques & Voas, 2010). This paper assesses the evidence for the effectiveness of AIP generally but is focussed on understanding the impact of a range of specific factors that have been suggested to enhance their effectiveness. The overall aim is to come to an understanding of the optimal design for an AIP.

Exploratory literature review: method and results

An exploratory search of four indexed databases was conducted (PubMed, Medline (Ovid), PsychINFO, Google Scholar). The search string developed included three key concepts and associated terms: (alcohol interlock) AND (evaluation OR effectiveness OR scheme OR program OR practice) AND (therapy OR counselling OR rehabilitation OR education OR treatment OR recidivism). The initial search yielded 948 records. An initial, high-level title and abstract scan eliminated: duplicates (e.g., conference papers covering the same study as journal articles), articles clearly out of scope (e.g., studies of alcohol biomarkers), or articles that merely mentioned alcohol interlocks as part of a more general consideration (e.g., articles about in-vehicle intelligent transport systems). After this initial scan, 79 publications with potential relevance were reviewed.

Only literature published in English was included. The focus was on peer-reviewed scientific literature; however, grey literature from a reputable source was also included. Research published since 2000 was given the highest priority, although earlier publications were included if pertinent to the area.

After the in-depth review, 40 publications were selected as being directly relevant to the aim of coming to an understanding of the optimal design for an AIP. The majority of these papers were from North America (n=34) with the remaining papers from Europe (n=4) and Australia (n=2). All except 3 papers were post 2000, 27 publications were refereed journal articles and 13 were technical reports.

Measuring the effectiveness of alcohol interlock programs

From the literature, four key metrics of the effectiveness of AIP were identified: offence recidivism, crashes, breath test violations, and program participation.

Drink driving recidivism

In a randomised control trial (RCT) evaluation of the Maryland AIP, Beck et al. (1999) found that, during the first year of the program, the rate of drink driving offences for people in the alcohol interlock group was nearly one-third that of people in the control group (2.4% versus 6.7%). This statistically reliable result (p < .05) equated to a 64 percent reduction in the risk of recidivism. However, in the second year, after the alcohol interlocks were removed, this difference disappeared.

In 2011, Rauch et al. published an updated RCT of the Maryland AIP that evaluated whether a two-year program duration impacted the program’s effectiveness. The risk of recidivism significantly reduced (26%) for offenders in the alcohol interlock program, relative to the control group, in the post-program period. This contrasts with the failure to find any such carry-over effect in Beck et al.'s 1999 study. Rauch et al. speculated that the extra year in the program allowed offenders enough time to learn to better manage their drinking and driving behaviour; in essence, breaking the nexus between drinking and driving.

An evaluation of Nova Scotia’s AIP (implemented in 2008) suggested the carry-over effect is not unique to the Maryland program (Vanlaar et al., 2017). The Nova Scotia AIP has both a voluntary and a mandatory stream. Over the duration of the 2-year program, the control group had a recidivism rate of 8.9 percent, the voluntary interlock group had a recidivism rate of 0.9 percent and the mandatory interlock group had a recidivism rate of 3 percent. After exiting the program, the voluntary group had a recidivism rate of 1.9 percent and the mandatory group had a recidivism rate of 3.7 percent, both of which were significantly less than the control group (p < .001) and represented a reduction in recidivism (compared to the control group) of 90 percent in the voluntary group and 79 percent in the mandatory group after exiting the program.

Like the Rauch et al. (2011) study, these results suggest that a carry-over effect is possible from an AIP. Indeed, the Nova Scotia evaluation indicates an even greater (more than double) reduction in recidivism from participation in the program carrying over after participants have exited the program. Vanlaar et al. (2017) hypothesised that this substantial carry-over effect is the result of the treatment component that is an integral part of the Nova Scotia program.

Crashes

In 2004, the AIP in Washington State was extended to include all first-time offenders. McCartt et al. (2013) analysed the impact of the extension and found an 8.3 percent reduction in single-vehicle late-night crashes, which are recognised as a surrogate for alcohol-related crashes (Voas et al., 2009).

Between 2004 and 2013, 18 US states made alcohol interlocks mandatory for all drink driving convictions. Following the change, Kaufman and Weibe (2016) compared the alcohol-involved crash fatalities in these states with 32 states without the universal interlock requirement, while statistically controlling for a large number of potentially confounding factors. They compared the mean alcohol-involved fatality rate and reported that states with the universal interlock requirement had a lower rate (4.7 per 100,000) than states without the universal interlock requirement (5.5 per 100,000). The effect equates to a 15 percent reduction in alcohol-involved crash fatalities associated with a universal interlock requirement over and above partial interlock implementation. The magnitude of the fatality reduction attributable to alcohol interlocks per se would presumably be greater than this 15 percent reduction figure, as this represents the extra advantage of a universal scheme, over and above non-universal AIP.

In a similar study, McGinty et al. (2017) investigated the impact of AIP on alcohol-involved fatal crashes in the US from 1982 to 2013. Their analysis attributed alcohol-involved crash rate reductions to both partial and universal interlock schemes and reported a dose-response relationship between the interlock scheme type (partial vs. universal) and alcohol-involved crash fatalities. Depending on several assumptions, the estimated reduction associated with a universal scheme ranged from 7-10 percent and for a partial scheme ranged from 0-3 percent.

Using drink driver vehicle crashes from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System and National Automotive Sampling System’s General Estimates System data sets (2006-2010), Carter et al. (2015) modelled the impact of the mandatory fitment of alcohol interlocks into all new US motor vehicles. Assuming 100 percent effectiveness of interlocks, their results suggested that, over a 15-year time frame, 85 percent of alcohol-involved crash fatalities and up to 88 percent of nonfatal injuries from alcohol-involved driving would be prevented.

Blood alcohol content compliance

Vanlaar et al. (2013) examined AIP in three US states and found that compliance increased over time (i.e., lockouts decreased by around 50% in Texas and 35% in California and Florida). More recently, Vanlaar et al. (2017) found a similar pattern of results in their evaluation of the Nova Scotia AIP. These results are unlikely to be due to decreased driving, as there is evidence that the number of starts/breath tests while participating in AIP does not change (Marques, Voas, et al., 2010). It is also unlikely to be due to a decline in the amount of alcohol consumed, as the presence of alcohol biomarkers did not decline during program participation (Marques, Tippetts, et al., 2010). However, this result needs to be replicated more widely before its generalisability to other jurisdictions is clear.

This pattern of increased compliance over time represents something beyond temporary adaptation and is consistent with the results presented in Voas (2014), who tracked nearly 20,000 offenders over seven years and analysed their interlock and recidivism data. When participants were grouped according to the number of lockouts triggered in the six months the interlock was on the vehicle, there was a significant relationship between group membership and recidivism rate in the years after exiting the program, with fewer lockouts predicting less recidivism. Voas (2014) speculated that this information is likely to be useful for informing the need for and nature and timing of any education and treatment.

Program participation

The overall population-level effectiveness of AIP is likely to be dependent on the offender participation rate because of the increased risk of unlicensed driving in suspended drivers. For example, Ma et al. (2016) reported that more than half of drivers convicted of alcohol-impaired driving in Ontario, Canada, between 2005 and 2010 (around 30,000) decided against installing an interlock. These drivers exhibited a recidivism rate that was 60 percent higher during the interlock condition period than offenders who installed an interlock, even though they were banned from driving.

Some jurisdictions offer voluntary programs where the duration of the licence suspension period can be traded for participation in AIP. In contrast, there are mandatory programs where relicensing cannot occur without participation in an interlock program. Despite the apparent incentive of a reduced suspension period in a voluntary program, some studies found an uptake of only approximately 10 percent by eligible offenders (Beirness et al., 2003; Voas et al., 1999), with offenders preferring to wait out the suspension period. In contrast, in their evaluation of the Maryland AIP, Rauch et al. (2011) found that 78 percent of the nearly 2,000 eligible offenders elected to accept the alcohol interlock as a condition of relicensing when the alternative was potentially a lifelong suspension. In their recent survey of AIP in 25 US states, Robertson et al. (2018) found that 46 percent of the approximately 500,000 convicted alcohol offenders had an interlock installed, an increase on the survey in 2014 when the rate was 35 percent.

Factors impacting program effectiveness

Several factors have been suggested to modify, either positively or negatively, AIP effectiveness: performance monitoring, program duration, attitudes and perceptions, incentives and sanctions, program reach, unintended consequences, and education and treatment.

Performance monitoring

Zador et al. (2011) investigated the role of closer monitoring on BAC compliance in the Maryland AIP, with more than 2,000 drink driving offenders assigned randomly to either the standard program or a more closely monitored version of the program. They found that the more closely monitored group had approximately 50 percent lower non-compliance rates than the group participating in the standard program. There were several elements of the closely monitored program that differed from the standard program (information provision, threat of sanctions, performance-based contingencies), so it is difficult to identify the important elements. Nevertheless, these results suggest the need for a closely monitored, performance-based program incorporating good feedback.

Program duration

While there are examples of different program durations in the literature, in general there are many other differences between these programs that make it difficult to draw conclusions on the impact of duration. One exception is the Maryland evaluation by Rauch et al. (2011), where they assessed whether recidivism would be reduced more effectively in a two-year interlock program compared to a one-year program (Beck et al., 1999). While the one-year program found no evidence of a carry-over effect, the two-year program found a significant reduction (26%, p < .05) in the risk of recidivism for nearly 1,000 offenders in the AIP, compared to nearly 1,000 offenders in the control group during the two-year post-program period.

Attitudes and perceptions

Even when the alternative to AIP participation is lifelong licence suspension, a significant proportion of offenders still chose not to participate. In their evaluation of the Maryland program, Rauch et al. (2011) found that nearly 25 percent of eligible offenders elected not to accept the alcohol interlock as a condition of relicensing, even though they would be prohibited from ever driving legally again. Part of the reason for this is likely to be the low perceived risk of being detected driving while suspended and this highlights the importance of unlicensed driving enforcement for the success of alcohol interlock programs (Fitzharris et al., 2015).

There is also evidence of other barriers to participation in alcohol interlock programs. Marques et al. (2010) conducted focus groups as part of their evaluation of the New Mexico alcohol interlock program. What participants liked least about the interlock was the cost and the inconvenience of having to deal with the program and the device operating requirements.

Vehmas and Löytty (2013) surveyed participants in the Finnish alcohol interlock program. The majority of participants (95%) stated that the best aspect of the interlock was being able to keep driving. Important factors in favour of the interlock included enabling participants to keep their job (approximately 30%) and increased safety (approximately 30%). The worst aspect of the interlock was seen as the cost, with nearly 60 percent of participants identifying this aspect. More than 40 percent of participants were embarrassed about being observed using the device in public.

In a recent study investigating the Swedish alcohol interlock program, Forsman and Wallhagen (2019) surveyed program participants and non-participants to understand their reasons for that decision. Consistent with previous research (Vehmas & Löytty, 2013), cost was the main barrier to participation for 65 percent of non-participants.

Collectively these results suggest that cost may be the major perceived barrier to alcohol interlock program participation. Many jurisdictions offer means-tested cost subsidisation (as recommended in an NHTSA report; Marques & Voas, 2010), however no empirical evaluations on the impact of providing such subsidies were identified in this review.

Incentives and sanctions

Attempts to increase the participation rate in alcohol interlock programs vary from extreme sanctions to what seem like appealing incentives (Rauch et al., 2011; Voas et al., 2002). While there has been some success, no program has achieved full participation.

The most extreme sanction was in a program in Indiana that required drink driving offenders to participate in the AIP and install alcohol interlocks or face jail or house arrest (Voas et al., 2002). Despite the threat of jail, only 62 percent of the approximately 20,000 offenders entered the interlock program. An evaluation of the Maryland AIP (Rauch et al., 2011) found that even when the alternative to alcohol interlock program participation was permanent licence disqualification, 25 percent of the approximately 2,000 offenders elected not to participate in the program.

Some US states have developed programs that allow or require the installation of interlocks after an arrest rather than the offender having to wait for a formal conviction. Elder et al. (2011) discussed the New Mexico alcohol interlock program, which changed in 2003 to allow any drink driving offender whose licence had been suspended to present at the licensing authority with an interlock equipped vehicle and obtain a licence to drive an interlock equipped vehicle. However, even this simplified process had only achieved a participation rate of 25 percent by 2006.

In 2010 in Ontario, Canada a revised alcohol interlock program was introduced. The program was designed to increase participation in the alcohol interlock program primarily by offering a reduction in the hard suspension period, contingent upon interlock fitment. Previously, the hard suspension period was 12 months but could now be as short as three months. Ma et al. (2016) evaluated the impact of this policy change and found that interlock program participation significantly (p < .05) increased from approximately 0.45 to 0.70 installations per eligible driver.

Reach of interlock programs

Interlock programs have typically targeted repeat and high-BAC offenders. However, as Elder et al. (2011) point out, first-time drink driving offenders more closely resemble repeat offenders than non-offenders and the evidence suggests that interlock effectiveness is high with first-time offenders and should be used widely, even for low-level drink driving offences.

The reach of AIP can, and arguably should be extended outside of the domain of offenders only, and more widely used as a primary prevention strategy (Fitzharris et al., 2015). A strong argument for this position comes from the observation that only a very small proportion of drink driving trips are detected (Willis et al., 2004).

Unintended consequences

While one study reported an increase of up to 2.3 times in non-alcohol-related crashes in drivers in an AIP (DeYoung, 2002), a recent nationwide US study by Kaufman and Weibe (2016) found no evidence of any increase in non-alcohol-related crashes. However, their study assessed the incremental impact of a universal interlock program over a partial program so they may not have been able to detect the unintended consequences of interlocks per se.

Another significant unintended consequence associated with AIP is the risk of unlicensed driving (McCartt et al., 2003). This is likely among offenders who refused to participate in the program or who fit an interlock but drive another vehicle. The level of offence recidivism found in many evaluations indicates that a significant group of program participants are illegally driving other motor vehicles (i.e., not fitted with an interlock), although of course they may still have driven illegally in the absence of an AIP.

Education and treatment

In the CDC review, Elder et al. (2011) speculated that the effectiveness of AIP could be improved by combining their use with participation in an alcohol treatment program. Consistent with this, Miller at al. (2015) concluded that multi-component treatment programs for drink driving offenders are likely to be more effective than those that target only one aspect of the issue. Indeed, the one study Miller et al. (2015) reviewed that evaluated the effects of education alone found no reduction in recidivism at the one-year follow-up (Ekeh et al., 2011).

In 2008, the Florida AIP was changed to include a treatment component for participants who demonstrate BAC non-compliance. The Florida program was evaluated by Voas et al. (2016) to determine the extent the addition of this treatment component to the program reduced the level of recidivism in offenders following interlock removal. While in the interlock program, more than 600 offenders who showed two or more instances of BAC non-compliance within four hours were directed to attend mandatory individualised treatment sessions with a qualified counsellor for up to 12 weeks. When compared with a group of more than 800 offenders with similar demographic characteristics, drink driving history and interlock performance, the treatment group demonstrated a 32 percent (p < .05) reduction in drink driving recidivism. These results provide compelling evidence that a treatment program triggered by interlock BAC compliance violations can decrease recidivism for those offenders in the years after program exit.

As Miller et al. (2015) note, there are few rigorous evaluations of drink driving treatments, making it difficult to speculate what the optimal education and treatment program should look like, or how it should be integrated with alcohol interlocks. They do suggest that in addition to multi-component programs, individually tailored programs may be more effective due to the heterogeneity of drink driving offenders across numerous dimensions (e.g., alcohol dependence, attitudes, depression, see Nochajski & Stasiewicz, 2006). Mathias et al. (2019) administered the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) to assess the level of alcohol use/misuse and inform the intensity of intervention delivered to a sample of 982 drivers recently arrested for drink driving. They then used the guidelines from the World Health Organization (Babor & Higgins-Biddle, 2001) on the interventions that should be applied for different levels of alcohol misuse. In order of increasing severity, these vary from alcohol education, simple advice, brief counselling and continued monitoring, and brief counselling and referral to a specialist. They found that alcohol education was the most commonly clinically indicated intervention category and only approximately 25 percent of the sample scored within a range indicating a need for the more intensive interventions.

When a more intensive therapeutic intervention is clinically indicated, there is reason to believe there would be a benefit for drink driving recidivism from discussing the concrete circumstances and nature of interlock breaches as a central aspect of therapy (Voas et al., 2014). The program currently used in Colorado (Voas et al., 2014), comprises a motivational intervention program originally developed in Texas that provides individual and group counselling built explicitly around service provider interlock reports. In the counselling sessions, participants are presented with their monthly interlock records and encouraged to find actions that would avoid future breaches. The Colorado program has been evaluated (Lucas et al., 2018) and offenders who completed both the interlock and treatment component have a 50 percent lower recidivism rate than offenders who do not complete both components. While appropriate caution should be exercised in interpreting this result, it is suggestive of a greater impact from a counselling program focused on separating drinking and driving specifically, using interlock data as a key input to guide the counselling process, rather than a more generic counselling program (cf. Voas et al., 2016).

These considerations suggest that the treatment component in an alcohol interlock program should be able to identify and address the full range of levels of alcohol misuse in drink drivers and respond with an appropriate intervention. It points to a central role for assessment or screening within an alcohol interlock program and to a program with flexible content that is responsive to the assessment. In this vein, Filtness et al. (2015) recommended a 'stepped care’ approach whereby an offender, based on initial screening, is first exposed to the least expensive/invasive intervention which is likely to be effective. If breaches on the interlock occur, the intervention level is then escalated. Filtness et al. also discussed the options for assessing rehabilitation of drink driving offenders. They concluded that, although it is desirable to do so within the context of AIP, there was no research on the best way in which to determine whether rehabilitation was successful. They noted that the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) is likely to be the most thorough assessment tool but is very time consuming.

Suggested model AIP

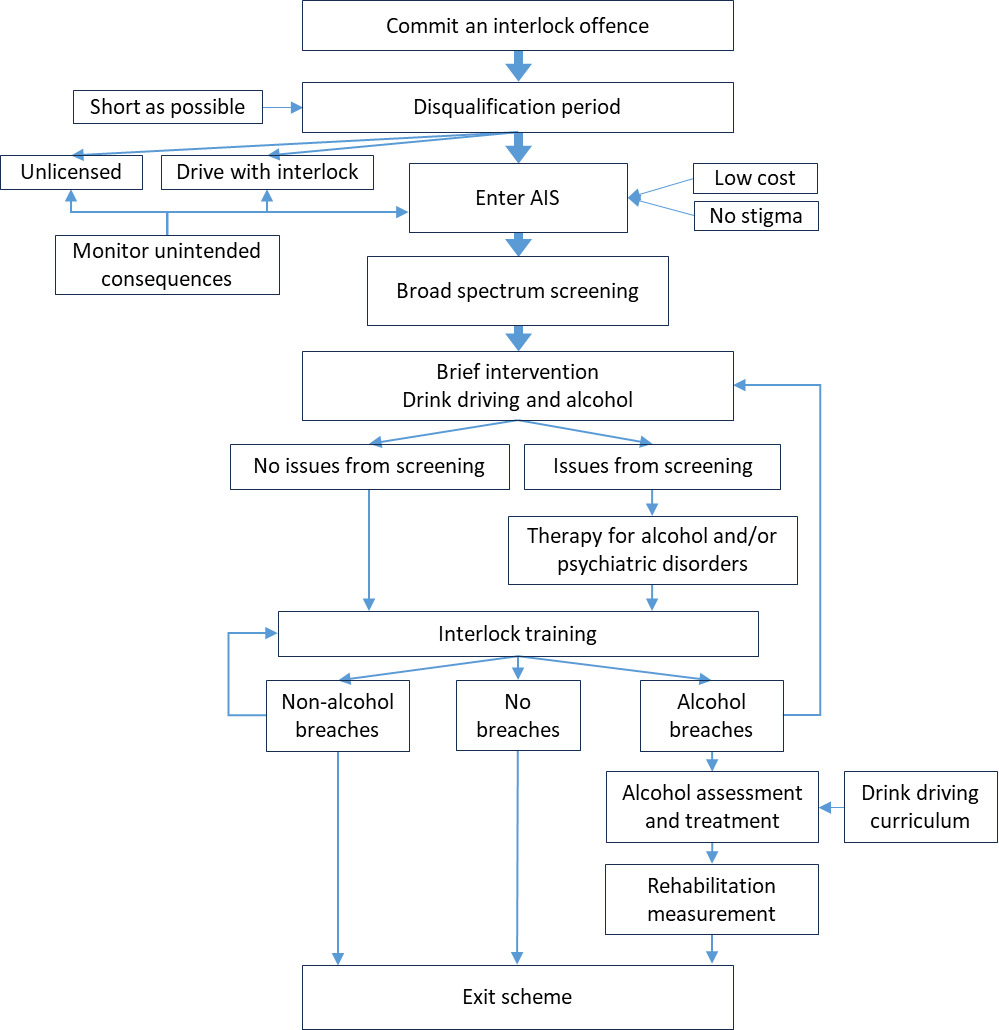

There are still gaps in the literature relating to exactly how an AIP should be constructed. For example, it is unclear what the optimal education and treatment program should contain, or exactly how rehabilitation should be assessed. While some conclusions are based on only a small number of evaluations conducted mainly in North America, nevertheless there is sufficient evidence to provide a preliminary and broad outline of what an optimal AIP might include. Based on the literature reviewed above, Figure 1 depicts a model that is considered a first pass at an optimal AIP.

After committing an alcohol interlock offence, offenders should be disqualified for as short a period as possible. In a voluntary program, offenders then elect to either remain disqualified, to drive with an interlock indefinitely, or to enter the AIP. In a mandatory scheme (preferred) all offenders enter the AIP immediately after the disqualification period with measures in place to detect unintended consequences, particularly unlicensed driving. Upon entry to the AIP, all offenders should be screened with a clinical tool such as the AUDIT to aid in guiding the appropriate level of therapeutic intervention. Following training on how to use the interlock, offenders who have no breaches in a specified period (up to two years may be beneficial) can exit the program. Offenders who are BAC non-compliant must enter an alcohol assessment and treatment program, ideally with a standard curriculum built around separating drinking and driving. Offenders who breach requirements of the scheme that are not alcohol related should be directed back to the interlock training module. Finally, there is merit in having a measure of rehabilitation prior to exit to further strengthen confidence that the offender will not relapse.

Conclusions

There is evidence that when fitted to an offender’s vehicle, alcohol interlocks reduce drink driving recidivism, and some evidence that they reduce crashes, although appropriate caution should be exercised because of the small number of studies in some of these areas. However, the impact of interlocks on recidivism once the device is removed from the vehicle is less, and offending behaviour may return to pre-instalment levels unless other measures are added to the program. When an education and treatment component is appropriately integrated into an AIP it can reduce drink driving recidivism by 50 percent compared to the interlock alone. The research suggests that key elements of an effective interlock scheme treatment component include a focus on separating drinking and driving, use of interlock data in counselling therapy, and the ability to provide a range of therapeutic approaches that vary in intensity, and which can be escalated based on interlock performance data and guided by standardised alcohol assessment instruments.

An issue for AIP worldwide has been the significant proportion of offenders who elect not to participate, even when mandatory or the alternative is permanent licence suspension. AIP will not achieve their road safety goal if offenders do not participate. The literature suggests that two factors in particular may have a positive impact on participation: reducing cost, and shorter suspension periods in exchange for participation in the AIP.

While the extant research is suggestive as to what an optimal AIP should include, there are many areas where this research could be strengthened or expanded to finesse the model AIP suggested here. Based on the literature reviewed, the two priority areas for further research are the nature of and optimisation of alcohol assessment and treatment within an AIP, and the best way, or combination of measures, for increasing AIP program participation.

Author contributions

Paul Roberts and Lynn Meuleners were involved in the conception, design, and execution of the reported study. Paul Roberts drafted the article. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded as part of the Western Australian Centre for Road Safety Research’s baseline funding from the Road Safety Commission of Western Australia.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.