Glossary

HIC High-income countries

LMIC Low- and middle-income countries

PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

TOD Transit-Oriented Development

Introduction

Road safety remains a critical issue in contemporary urban mobility, particularly as cities continue to expand and diversify in their transportation demands. Among all road users, pedestrians are the most vulnerable due to their exposure to vehicular traffic without the protective infrastructure available to motorised users. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2023), over 270,000 pedestrians are killed annually worldwide due to road traffic crashes, the majority in low- and middle-income countries. These figures underscore the urgent need for pedestrian-focused safety interventions and highlight a significant gap in current transport policy and urban design practices.

Historically, road safety research has predominantly focused on motor vehicle occupants, with infrastructure investments and traffic regulations often prioritising vehicle throughput over the safety of non-motorised users (Peden & Puvanachandra, 2019). However, recent global policy shifts, including the United Nations Decade of Action for Road Safety and the Sustainable Development Goals (particularly SDG 11.2), emphasise the importance of safe, inclusive, and sustainable mobility for all users, including pedestrians. Pedestrian safety measures have gained renewed relevance, particularly for informing policy in rapidly urbanising regions such as South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, where urban growth outpaces the provision of pedestrian infrastructure (Gwilliam, 2013; Tiwari & Jain, 2012).

Defining Pedestrian Safety

Pedestrian safety refers to the measures and conditions that protect people walking from the risk of injury or death due to traffic crashes and other urban hazards. It encompasses infrastructure design, traffic regulation, user behaviour, and environmental factors that reduce conflict between pedestrians and motorised vehicles (WHO, 2013a). According to Zegeer and Bushell (2012), pedestrian safety also includes perceived safety, which significantly influences walking behaviour and modal choice. Lee and Abdel-Aty (2005) identified the statistical risk associated with pedestrian-vehicle interactions, suggesting that safety can be quantitatively assessed by the likelihood and severity of crashes in given spatial and temporal contexts. Further, Schneider et al. (2004) expand the scope by incorporating both actual crash risk and perceived safety, recognising that subjective sense of security significantly affects people’s walking behaviour and route choice. In the context of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), pedestrian safety is crucial, as the success of TOD hinges on seamless, safe, and comfortable access to transit nodes by non-motorised users (Ewing & Cervero, 2010).

Given these perspectives, this research adopted a comprehensive definition of pedestrian safety as: the condition in which people walking in urban environments are protected from physical harm caused by traffic or environmental hazards, while also perceiving the walking environment as safe, accessible, and conducive to active travel. This definition emphasises both measurable safety outcomes and the perceptual factors that influence pedestrian behaviour and mobility choices.

The Need for Pedestrian-Focused Interventions

In high-income countries (HIC) such as Australia and New Zealand, pedestrian safety interventions have been extensively evaluated under Safe System principles. For instance, the Austroads reports (AP-R728-25 and AP-R730-25) reveal strong evidence that integrated measures (e.g., speed reduction, pedestrian-priority crossings, infrastructure redesign) are effective in reducing fatalities, especially when supported by enforcement and communication strategies. In Europe, countries like Sweden and the Netherlands emphasise urban design (e.g., woonerfs, raised crossings) and speed control, showing consistent reductions in pedestrian deaths under Vision Zero strategies.

In contrast, evidence from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), particularly in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, indicates challenges in implementation and enforcement, though isolated success stories (e.g., pedestrian bridges, signalised crossings in India and Kenya) show promise when interventions are contextually tailored and supported by community engagement (Haque et al., 2024; Mitullah et al., 2017). These findings underscore that effectiveness is strongly mediated by institutional capacity, urban form, and behavioural norms.

While several studies have explored individual safety interventions (e.g., speed bumps, raised crossings, pedestrian signals, refuge islands), their application, effectiveness, and contextual suitability vary widely across geographies. For instance, traffic calming measures in high-income countries have demonstrated statistically significant reductions in pedestrian fatalities and injuries (Retting et al., 2003), but similar interventions in lower-income contexts often face barriers related to maintenance, enforcement, and urban planning priorities (Tiwari & Mohan, 2016). Additionally, pedestrian behaviour, cultural norms, and land use patterns shape the effectiveness of safety measures, yet these factors are often overlooked in the design and implementation phases.

Rationale and Objectives

Despite the availability of a growing body of literature, there remains a lack of consolidated understanding of how various pedestrian safety measures function across different urban contexts. Furthermore, much of the existing evidence is fragmented, focusing on isolated interventions or single-case evaluations, without providing a comparative or integrative perspective that can inform scalable and adaptable safety strategies.

The aim of this review was to fill this knowledge gap by presenting a cohesive narrative on the types of pedestrian safety measures that have shown effectiveness, the conditions under which they work best, and the limitations in current approaches that hinder broader impact. The emphasis was on contextual diversity and cross-disciplinary integration. Also, this study took a broader discipline approach and expanded the typical engineering or public health perspectives to incorporate insights from urban planning, behavioural science, and policy evaluation. The study also focused on pedestrian safety challenges in the low- and middle-income countries that are frequently underrepresented in international literature but disproportionately affected by pedestrian injuries and fatalities (Naci et al., 2009).

There were three key justifications for this research:

-

Persistent pedestrian vulnerability: Despite global advances in road safety, pedestrians continue to bear a disproportionate burden of road trauma, and this is especially acute in rapidly urbanising regions (WHO, 2023).

-

Fragmentation in existing literature: Previous research offers valuable insights but often lacks synthesis, comparability, and consideration of contextual factors, which are essential for scaling up interventions (Sharma et al., 2024; Singh et al., 2024).

-

Policy and practice relevance: With many cities seeking to promote active transport as part of climate action and sustainable urban mobility plans, pedestrian safety is both a public health issue and essential for equitable and resilient cities (Litman, 2021).

Method

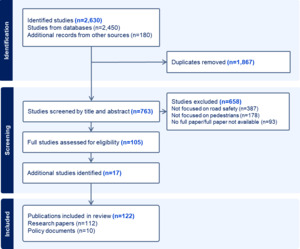

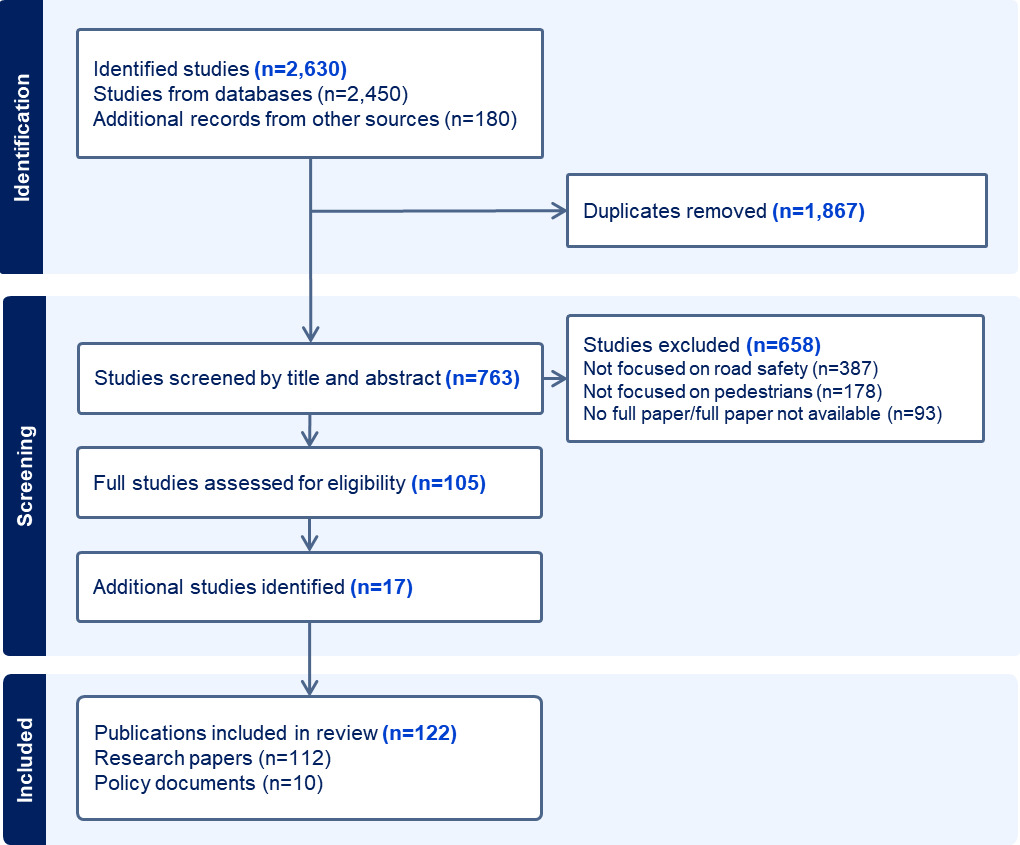

This study followed a systematic literature review protocol: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021). The objective was to identify, evaluate, and synthesise high-quality evidence on interventions that have demonstrably contributed to improving pedestrian safety outcomes across diverse urban contexts. The final search was conducted on 30 March 2025.

Literature search and contextual scope

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were:

-

topic relevance: studies must have evaluated or discussed pedestrian safety interventions, including but not limited to infrastructure changes, policy tools, behavioural interventions, or enforcement strategies.

-

publication type: peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, systematic reviews, government reports, and relevant grey literature from reputable sources (e.g., WHO, World Bank, transport authorities).

-

publication date: published between January 2000 and March 2025 to ensure contemporary relevance.

-

language: only publications in English were included.

-

geography: this was a global search and studies from all countries were included.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

did not focus on pedestrians: general road safety research without specific reference to pedestrians

-

publication type: opinion pieces or editorial notes lacking empirical analysis, or reported on safety outcomes without evaluating interventions or providing recommendations.

Information sources and search strategy

The electronic databases searched included Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, TRID (Transport Research International Documentation), ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar (for grey literature and policy documents). Search terms were crafted using Boolean operators and combinations of key phrases such as: \pedestrian safety\ AND (\traffic calming\ OR \speed reduction\ OR \safe crossings\ OR \urban design\ OR \road infrastructure\ OR \walkability\ OR \enforcement\ OR \behavioral interventions\.

Study selection

The selection process followed PRISMA’s four-step flow:

-

Identification: All search results were imported into Mendeley and duplicates were removed.

-

Screening: Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers to ensure alignment with eligibility criteria.

-

Eligibility: Full-text articles were retrieved for studies that met screening criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

-

Inclusion: A total of 92 studies were included in the final synthesis.

Data extraction and synthesis

A standardised data extraction form was used to extract study variables (e.g., country, type of intervention, methodology used, citation counts, pedestrian safety interventions), measured outcomes (e.g., crash reduction, user perception, compliance rate) and contextual factors (e.g., urban setting, income level, pedestrian demographics). The data were thematically grouped and analysed using a narrative synthesis approach to identify patterns, effectiveness, and contextual variations across interventions. Due to the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes, it was not possible to conduct a quantitative meta-analysis.

Quality Assessment

All included studies were assessed for methodological quality using a modified version of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018). Studies were not excluded based on quality but were flagged in the synthesis to guide interpretation of findings and confidence in results.

Thematic Analysis Approach

To ensure our categories reflect both a rigorously developed conceptual framework and the empirical evidence, we employed a hybrid thematic analysis combining deductive (framework-driven) and inductive (data-driven) coding stages.

Framework Development and Deductive Coding

Initial Framework Construction: We synthesised an a priori framework comprising four domains drawing on key sources (e.g., WHO Pedestrian Safety Manual 2013; Zegeer & Bushell, 2012; Austroads AP-R728-25):

-

Infrastructure Design: footpaths, sidewalks, crossings, lighting

-

Speed Management: traffic calming, posted speed limits

-

Regulatory and Enforcement Measures: legal penalties, enforcement intensity

-

Educational and Awareness Interventions: public campaigns, school programs

Deductive Coding: Using qualitative-analysis software (NVivo), we imported all selected studies and reports, then applied “parent” codes corresponding to these four domains. Each document was reviewed line-by-line, and passages matching one of these domains were tagged accordingly. This step ensured that our primary categories were grounded in established theory and practice.

Inductive Coding and Category Refinement

Open coding for emergent themes: after completing the deductive pass, we conducted a second review without reference to the initial categories, allowing unexpected themes (e.g., “micromobility integration,” “perceived safety metrics,” “equity considerations”) to surface. We created new codes for these recurrent concepts, ensuring no significant insight was overlooked. Codebook consolidation: we then merged overlapping codes and organised them hierarchically under broader themes. For instance, “micromobility integration” and “e-scooter safety” were grouped under a new sub-domain of Emerging Mobility Technologies. Cross-validation: two researchers independently coded a random sample of articles (20%). Inter-rater reliability indicated strong agreement (Cohen’s kappa = 0.85). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, further refining our code definitions.

Final thematic structure

Through iterative comparison of the deductive and inductive codes, six final themes emerged. Four from our initial framework and two identified from the data. This hybrid approach ensures that our taxonomy of pedestrian safety measures is both theoretically informed and empirically validated, avoiding ad hoc categorisation and providing clear transparency into how each theme was derived.

Adoption of the Safe System Framework and Road Safety Management Functions

To enhance transparency and coherence in categorising pedestrian safety measures, we adopted the Safe System framework, a globally endorsed structure for road safety analysis (Austroads, 2023; WHO, 2013b). This framework groups interventions under five key pillars:

-

Safe Roads: infrastructure that reduces crash likelihood and severity (e.g., pedestrian crossings, footpaths, traffic-calming).

-

Safe Speeds: speed limit enforcement, zone-based speed design, and signage.

-

Safe Vehicles: vehicle design standards for pedestrian impact mitigation.

-

Safe People: education, awareness, behaviour modification, enforcement.

-

Post-Crash Care: emergency response systems, first-aid training, trauma management.

In parallel, we mapped relevant management-level interventions to Road Safety Management functions based on the Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety and Austroads Keeping People Safe reports (AP-R728-25; AP-R730-25). These include:

-

Legislation and Regulation

-

Funding and Resource Allocation

-

Coordination and Governance

-

Promotion, Communication, and Engagement

-

Monitoring, Evaluation, and R&D

This dual-framework approach allowed us to categorise each identified intervention or strategy from the literature under both its operational level (Safe System component) and governance mechanism (Management function), creating a transparent, traceable classification that enhances the replicability and policy relevance of this review.

Contextual Factors within the Safe System Framework

In line with our adoption of the Safe System framework and Road Safety Management functions, we define “contextual factors” as the specific spatial, functional, behavioural, and institutional variables that influence both the risk profile and effectiveness of pedestrian safety interventions. These factors help determine how safety measures interact with the built environment and governance systems, and are categorised as follows:

-

Street hierarchy and road function (Safe roads, Safe speeds)

We differentiate between road types (e.g., arterials, collectors, local streets) as each poses distinct pedestrian safety challenges. For example, arterial roads with high-speed traffic require grade-separated crossings or signalised intersections while local streets benefit from traffic calming and shared street treatments.

-

Traffic volume, speed environment, and conflict density (Safe speeds)

Measures including speed limit enforcement, area-wide speed zoning, and signage were assessed in relation to traffic volumes and typical vehicle speeds, which significantly impact pedestrian crash risk and injury severity.

-

Land-use composition and urban density (Safe roads, Safe people)

We assessed the level of land-use mix (e.g., residential, commercial, institutional) and pedestrian activity, particularly in transit-rich or transit-oriented development (TOD) areas. High footfall areas require frequent crossings, enhanced footpaths, and targeted driver and pedestrian behaviour change campaigns.

-

Movement & Place classification (Safe roads, Safe people)

Drawing on the Movement & Place framework, we considered whether roads serve primarily transport functions, place-based civic roles, or both. Interventions are tailored accordingly, with high “place” value areas receiving pedestrian-priority designs and public realm improvements.

-

Institutional and socioeconomic readiness (Governance functions)

Drawing from the Road Safety Management components, we include policy and institutional capacity as key contextual factors, such as the presence of coordinated agencies, funding availability, and capacity for enforcement, education, and post-crash response.

By integrating these contextual factors into our dual-framework analysis, we ensure that each intervention is categorised by type (e.g., Safe Roads or Safe People) and also evaluated in terms of its appropriateness and operational feasibility within specific urban conditions. This enhances the practical relevance and transferability of our findings for diverse global cities and regions.

Results

A total of 122 studies were included in this review following the PRISMA screening process (Figure 1). The studies span various geographic locations and methodologies, offering a comprehensive view of effective pedestrian safety measures.

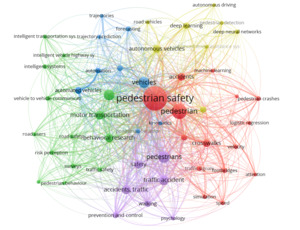

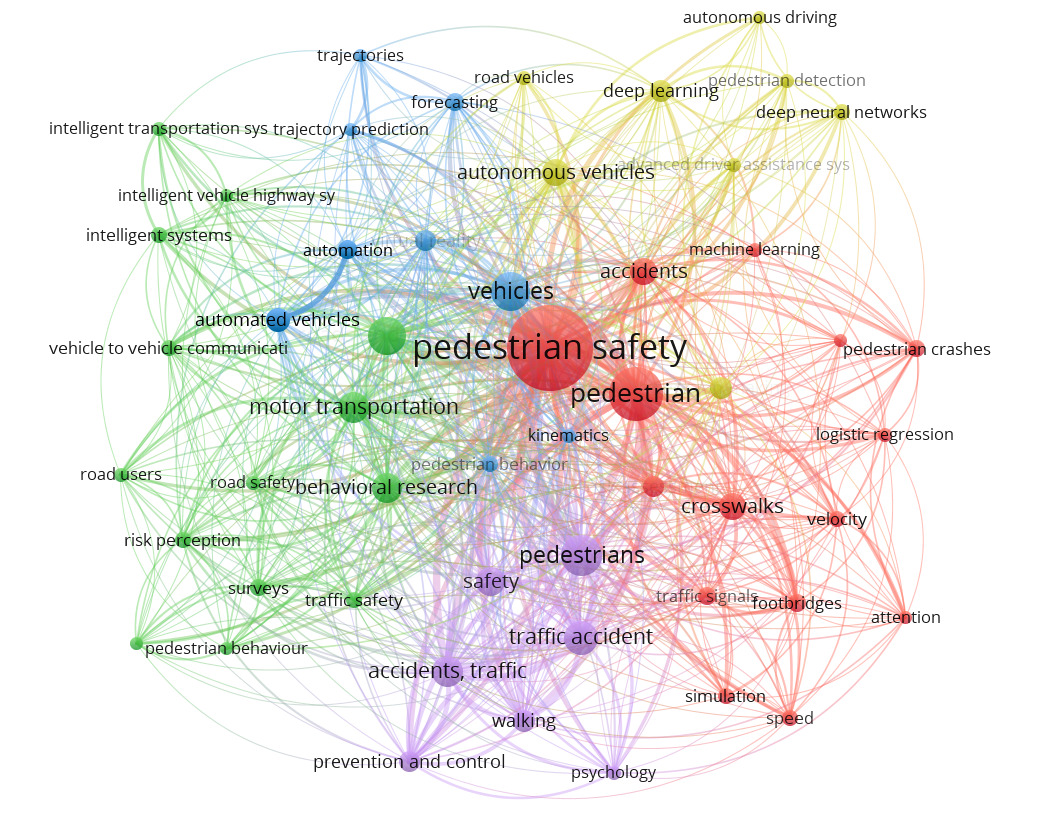

Keywords Analysis

The keyword analysis as shown in Figure 2 revealed recurring themes in pedestrian safety literature, emphasising infrastructure-based interventions such as traffic calming, pedestrian signals, and speed enforcement. Frequent keywords included “pedestrian safety,” “urban design,” “road traffic injuries,” and “built environment,” reflecting a multidisciplinary approach. Studies commonly integrated terms like “behavioral response,” “risk perception,” and “public awareness,” indicating growing interest in socio-psychological dimensions. Additionally, emerging mobility trends and “vulnerable road users” were notable, highlighting the evolving focus of research toward inclusive, data-driven, and context-specific solutions for safer pedestrian environments in both developed and developing countries.

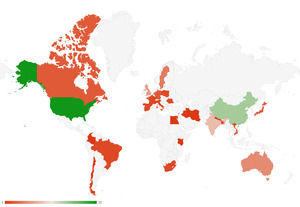

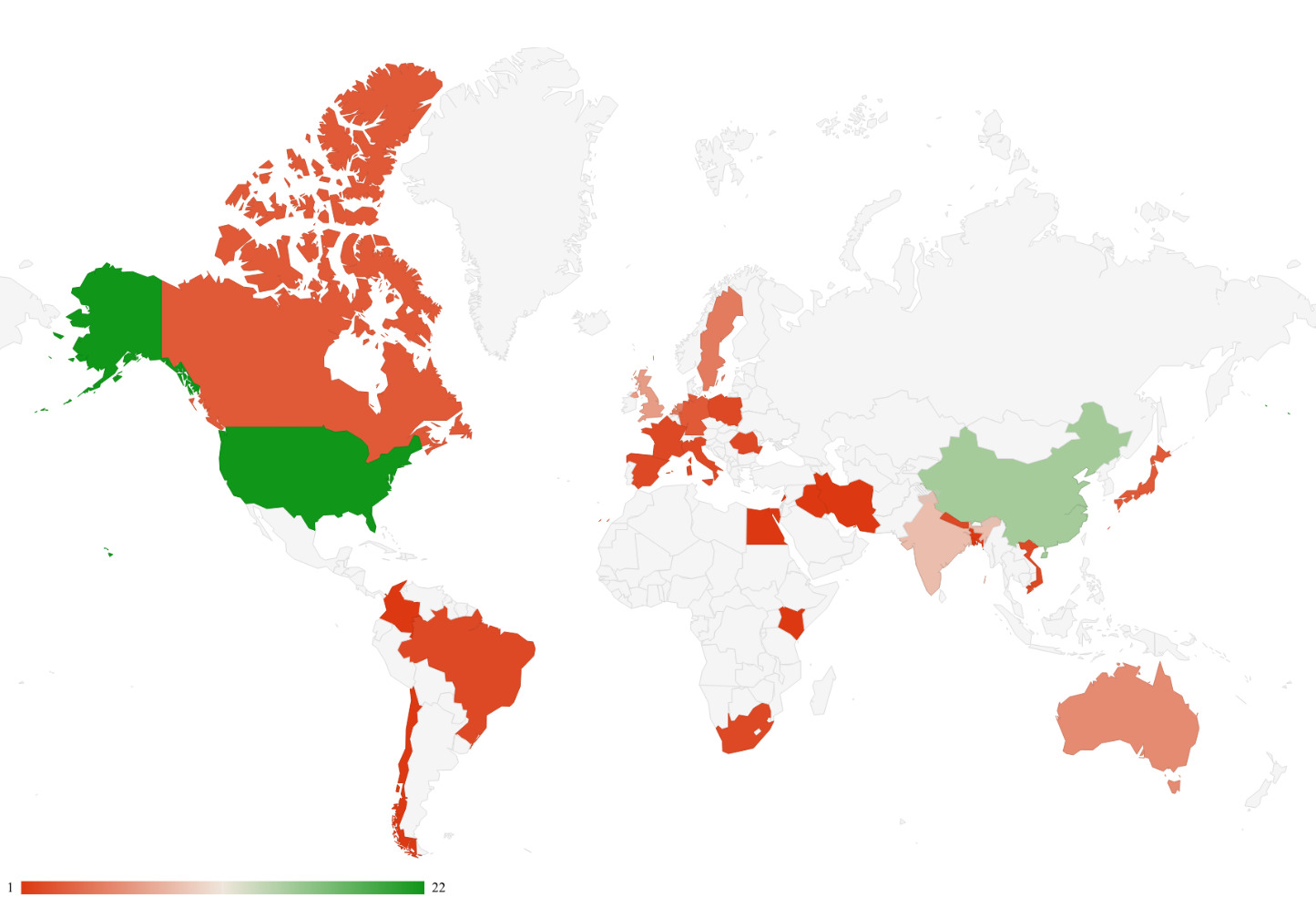

Geographical Distribution of Research

The geographical distribution (Figure 3) of pedestrian safety studies highlights a global interest in the subject, with notable concentrations in developed and emerging economies. The most studies were conducted in the United States of America (n=22), followed by China (n=15), India (n=9), the United Kingdom (n=7), and Australia (n=6). Other European contributions came from Sweden (n=5), the Netherlands (n=5), Japan (n=3), Germany (n=3), Canada (n=3), Italy (n=2), Spain (n=2), Romania (n=2), France (n=2), and Poland (n=2). Studies were also included from South Africa (n=2), Kenya (n=1) Vietnam (n=2), Nepal (n=2), Colombia (n=1), Chile (n=1), Lebanon (n=1), Iran (n=1), Iraq (n=1), Egypt (n=1), and Bangladesh (n=1).This shows the growing global concern and research into pedestrian safety. Europe, Australia, and New Zealand have been at the forefront of pedestrian safety research and implementation, offering valuable insights into effective strategies.

The review highlights varied effectiveness across intervention categories in enhancing pedestrian safety. Infrastructure and traffic calming measures were the most studied (45 studies) and showed high effectiveness in reducing crashes and speeds, particularly in the USA, Australia, and India. Signalisation and speed management interventions (30 studies) also proved highly effective, improving compliance and reducing delays. Enforcement and policy strategies (24 studies) demonstrated moderate to high impact, with notable success in Brazil and South Africa.

While only 10 studies focused on urban planning interventions, improved walkability and safety perceptions, especially in the Netherlands and Canada, the effectiveness of these interventions were moderate to high. Public education efforts (15 studies) contributed moderately to raising awareness and changing behaviour with moderate effectiveness. (Table 1).

Adoption of the Safe System Framework and Road Safety Management Functions

To enhance transparency and coherence in categorising pedestrian safety measures, we adopted the Safe System framework, a globally endorsed structure for road safety analysis (Austroads, 2023; WHO, 2013b). Safe System Approach is an integrated framework to improve pedestrian safety recognising that humans make mistakes and crashes on the road will occur. The emphasis is on creating the transport system to prevent fatalities and severe injuries. All five pillars, Safe Roads, Safe Speeds, Safe Vehicles, Safe People, and Post-Crash Care, combined create a strong and inclusive urban transport ecosystem. Since the burden of pedestrian injuries is disproportionately high in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in highly populated urban cities (e.g., Delhi), an integrated, evidence-informed, and people-oriented safety strategy is even more imperative.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of studies across different intervention categories. Each category is discussed in detail below.

Safe roads

The quality and form of road infrastructure are primary determinants of pedestrian safety in urban settings (WHO, 2023). Studies reliably demonstrate that the lack or insufficiency of pedestrian-specific infrastructure (i.e., footpaths, crosswalks, pedestrian islands, curb extensions), greatly elevates the risk of pedestrian harm and fatality (Feliciani et al., 2020). Urban space tends to accommodate motor vehicle travel over non-motorised users, especially in low- and middle-income nations where informal pedestrian movement is prevalent due to ill-integrated facilities. According to a research work by Zhu et al. (2021), conflicts involving pedestrians can be up to 40 percent higher at intersections with no visibly demarcated pedestrian crossings compared to demarcated crossings.

Inclusion of traffic-calming features on urban roads (e.g., speed humps, chicanes, narrowed roads) decreases the frequency and severity of pedestrian vehicle crashes even further (Tumminello et al., 2023). Such facilities can decrease pedestrian injury by up to 60 percent in high-risk areas (WHO, 2013b). Also, the idea of “complete streets” has become prominent in Western nations and is being transformed in Indian cities under initiatives like Smart Cities Mission and NMT policies. Complete streets guarantee that everyone can use the road safely including pedestrians, cyclists, drivers of all ages and abilities (Smart Growth America, 2016). With cities’ increase in density, a shift is needed towards inclusive street design that prioritises pedestrians through reserved walk space, safe intersections, barrier-free designs, and universal accessibility features.

Evidence from 21 studies conducted in high-density urban areas showed that the implementation of such measures led to a reduction of up to 40 percent in pedestrian collisions, highlighting their effectiveness in areas with high foot traffic. Raised crosswalks and refuge islands, in particular, were effective in reducing vehicle speeds and offering pedestrians safe stopping points on wide roads.

In LMIC such as India and Brazil, the presence of formal pedestrian infrastructure was strongly correlated with better safety outcomes. In areas that lacked such infrastructure, introducing basic features (e.g., footpaths, zebra crossings) significantly decreased pedestrian exposure to traffic risks (Hussain et al., 2021; Kadali & Vedagiri, 2020; Li et al., 2021; Zegeer & Bushell, 2012). These findings emphasise that even low-cost infrastructure improvements can yield substantial benefits in reducing pedestrian trauma, especially in low- and middle-income settings where pedestrian movement often intersects with high-speed vehicular traffic. Such interventions, when scaled and maintained, can create safer and more walkable urban environments globally.

Infrastructure technology to support safe behaviour are complementary tools in promoting pedestrian safety, particularly in high-risk or vulnerable populations. Innovations such as smart crosswalks, audible pedestrian signals, and LED in-pavement lighting are effective in increasing pedestrian visibility and reducing conflicts at crossings. These technologies are especially beneficial for children, older adults, and persons with visual impairments, as they enhance cues for safe crossing and alert drivers more effectively in real-time (Hussain et al., 2021; Larue et al., 2020; Y. M. Lee et al., 2022; Osborne et al., 2020; Zegeer & Bushell, 2012).

Safe speeds

Speed is among the most important factors that affect not only the probability of pedestrian crashes but also their severity (Abdel-Aty & Wang, 2017). Research indicates that even minor speed reductions significantly reduce pedestrian fatality risks (WHO, 2017). For instance, at a vehicular speed of 30 km/h, the chances of a pedestrian fatality are around 10 percent, while at 50 km/h, the chances increase to over 80 percent (Dean et al., 2023). Zone-based speed planning, especially in residential zones, school zones, and business districts, has been adopted in several cities around the world to improve pedestrian safety. The “Vision Zero” strategy, adopted by cities such as Stockholm and New York, focuses on reducing speed limits on pedestrian-concentrated streets to minimise traffic fatalities (Evenson et al., 2023). In India, while the Motor Vehicles Amendment Act (2019) gives states the jurisdiction to set speed limits, enforcement is inconsistent and usually ineffective (Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India, 2019, August 9).

Proper signage and enforcement are critical complements to speed-limiting. The standalone static signage is not particularly effective unless supported by enforcement systems including speed cameras, radar feedback signs, and police patrols in visible areas (Yasanthi et al., 2024). Automated enforcement systems are found to reduce average speed and crash rates effectively, particularly in areas with high pedestrian presence (Pineda-Jaramillo et al., 2022). Urban transport planning needs to incorporate engineering, education, and enforcement measures into the speed management approach to provide a safe speed. Further, the use of Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS), such as variable message signs and dynamic speed adaptation based on pedestrian presence, can be effective tools for adaptive speed adjustment (Noble et al., 2016). Research evidence supports the need to plan for and enforce reduced vehicle speeds in pedestrian-dominant zones for increased urban road safety.

Implementing the traffic calming measures and improving driver awareness in pedestrian-heavy areas is important. Speed humps, lane narrowing, and chicanes have consistently shown effectiveness in slowing down traffic near schools, residential neighbourhoods, and commercial zones with high pedestrian activity (Rao et al., 2025).

Eighteen reviewed studies reported that implementing area-wide speed limit reductions, particularly to 30 km/h reduced the average vehicle speed by 8 to 12 km/h. These reductions lowered crash risk and significantly improved driver yielding behaviour at pedestrian crossings. Slower vehicle speeds directly correlate with reduced collision severity and increased survival rates for pedestrians in a crash. Findings support the broader application of traffic calming strategies as a cost-effective and impactful approach to creating safer streets for all users, especially vulnerable pedestrians.

Safe motor vehicles

Motor vehicle design regulations are a vital aspect of pedestrian safety. Contemporary motor vehicle safety can no longer just encompass protection of occupants but must also reduce harm to vulnerable road users in the case of impact. Advances in technology, including softer bumpers, energy-absorbing front structures, pedestrian airbags, and active bonnet systems, aim to mitigate injury severity in impacts (Hernandez et al., 2024). The New Car Assessment Programs in Europe and Australia (Euro NCAP, ANCAP) and other programs across the world have also integrated pedestrian protection standards in their safety ratings (Mulhall et al., 2024), which puts pressure on motor vehicle manufacturers to implement pedestrian safety features. However, in most developing nations, including India, motor vehicle regulations remain more concerned with occupant protection than pedestrian safety.

Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) are another important innovation for pedestrian safety (Masello et al., 2022). Options including pedestrian detection, automatic emergency braking (AEB), lane-keeping assist, and night vision have been demonstrated to lower pedestrian crashes dramatically, especially in low-visibility and high-speed environments. However, these technologies are largely in more expensive cars creating a challenge for implementation in developing environments where the fleet is filled with smaller and older cars. Motor vehicle size also contributes to the severity of pedestrian injury, with research suggesting that SUVs and trucks have higher chances of inflicting deadly injuries than smaller vehicles (Li et al., 2021). Thus, city safety strategies need to increase pedestrian safe motor vehicle policies, including incentives and public procurement.

Safe People

Enforcement, education and policy interventions are critical in shaping road user behaviour and ensuring compliance with pedestrian safety regulations (Giri et al., 2024). Enhanced enforcement strategies, such as automated speed cameras, red-light enforcement, and stricter monitoring of pedestrian right-of-way laws, were associated with significant improvements in driver compliance and reduced pedestrian risk. Areas with active enforcement showed a marked decrease in unsafe driving behaviours, including speeding and failure to yield at crossings.

Pedestrian safety outcomes were more impactful when enforcement measures were paired with public awareness campaigns. Educational initiatives raised awareness about pedestrian rights and safe driving practices, fostering a culture of shared responsibility on the road. These combined efforts led to immediate behavioural changes and sustained safety benefits over time. Consistent enforcement, backed by supportive policy and public engagement, was essential to creating long-term improvements in pedestrian safety and reducing road trauma (Evenson et al., 2023; Giri et al., 2024; Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India, 2019; Yasanthi et al., 2024).

Behavioural focused interventions had modest positive impacts for programs including school-based pedestrian safety training and community outreach. These programs focus on building awareness, encouraging safe crossing habits, and fostering a safety-first mindset among pedestrians and drivers alike. Studies indicated that these initiatives contribute to long-term cultural shifts and improved safety outcomes. Together, technological upgrades and behaviour-focused strategies provide a holistic approach to enhancing pedestrian environments and reducing crash risks (Evenson et al., 2023; Larue et al., 2020; McIlroy et al., 2020; Osborne et al., 2020).

Post Crash Care

As identified in the Safe System approach, people make mistakes and crashes will occur, making post-crash response critical factor in minimising the long-term impacts of pedestrian trauma. Optimal emergency and trauma care provided within an acceptable time, ideally the ‘Golden Hour’ can reduce fatalities and major disability from crashes by 25 percent (WHO, 2013b). Post-crash care is initiated by quick notification systems including emergency call buttons, bystander alerts, and automatic crash detection through in-vehicle technology or smartphone apps (Jiang et al., 2023). Advanced nations have incorporated emergency numbers and response infrastructure within Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) to speed up medical intervention. Developing cities, on the other hand, often do not have coordinated emergency medical systems (EMS), paramedics with training, or even operational ambulances capable of trauma treatment (Dean et al., 2023; Hosseinzadeh et al., 2022; Naci et al., 2009; WHO, 2023).

Post-crash treatment also encompasses the capacity at hospitals and health facilities to manage trauma promptly. Educating first responders such as police officers, fire fighters, and civilians in basic life support and first aid can fill the gap before paramedics arrive (Bartolozzi et al., 2023). Legal systems like India’s Good Samaritan Law are intended to safeguard bystanders who help crash victims, but trust and awareness are low (Giri et al., 2024; Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India, 2019). Trauma registries, establishing EMS standard operating procedures, and funding mobile medical units are additional measures needed to provide a continuum of care (Hosseinzadeh et al., 2022).

Top 10 studies

This is the analysis of the top ten components of the pedestrian safety measures based on the literature review of the 75 research papers published in the last 5 years (Table 3, Figure 5). Table 2 lists 75 papers which has provided the design interventions. In those remaining studies such urban design measures were not explicitly explained or provided.

The Principal Component Matrix (as depicted in the Table 3 and Figure 5) reveals three key components underlying pedestrian safety measures. PC1 is strongly influenced by pedestrian signals, speed enforcement, and awareness, indicating a focus on regulatory and behavioural interventions. PC2 highlights enforcement and median islands, suggesting a component oriented toward physical and institutional safety structures. PC3 is defined by lighting and urban design, representing environmental and perceptual enhancements. Negative loadings on elements like traffic calming and zebra crossings in PC1 and PC2 imply their inverse relationship with regulatory measures. Overall, PCA effectively distinguishes distinct dimensions—behavioural, structural, and design-based—essential for integrated pedestrian safety planning.

Critical Evaluation and Identification of Key Gaps in Pedestrian Safety Research and Practice

Despite an expanding body of literature on pedestrian safety, this review—guided by the Safe System framework and Road Safety Management functions—reveals notable gaps and inconsistencies in both research focus and practical implementation. A more critical synthesis was essential to distinguish between well-substantiated findings and those that remain underexplored or inconsistently reported. By evaluating literature through a dual lens of intervention design and institutional mechanisms, we identify several systemic weaknesses that merit scholarly and policy attention.

Lack of context-sensitive evaluations in LMIC

Most pedestrian safety studies originate from high-income countries (HIC, n=66), which often benefit from well-established infrastructure, regulatory enforcement, and institutional coordination. In contrast, LMIC are underrepresented in empirical evaluations, despite experiencing disproportionately high rates of pedestrian fatalities. Few studies tailored the methodologies to account for informal transport patterns, limited pedestrian facilities, or institutional constraints typical of LMIC. Consequently, global best practices may not always translate effectively into these diverse, resource-constrained settings. This geographic and contextual skew restricts the development of evidence-based strategies that are locally feasible and culturally appropriate.

Insufficient integration of governance-level strategies

Another gap concerns the limited incorporation of governance functions into intervention evaluations (e.g., legislation, funding, coordination, inter-agency cooperation). Although these factors significantly influence the scalability and sustainability of safety measures, they are often treated as peripheral to infrastructure and behaviour-focused solutions. For instance, a speed-calming intervention may show limited success in environments where enforcement is weak or funding is inconsistent. The Road Safety Management framework emphasises that technical measures alone are insufficient without supportive institutional structures, yet this connection is seldom analysed in a structured manner across studies.

Contradictions and methodological variability

Our review also uncovered inconsistencies in intervention outcomes. For example, while pedestrian crossings and traffic-calming devices are broadly recommended, their reported effectiveness varies. Some studies reported substantial crash reductions while other studies reported negligible impact due to non-compliance or poor maintenance. These contradictions are rarely investigated in-depth. Methodological variability further complicates cross-study comparison, such as inconsistent definitions of “pedestrian safety,” lack of control groups, short evaluation periods, or reliance on self-reported data. The absence of standardised metrics limits our ability to synthesise findings and draw generalisable conclusions.

Narrow scope of evaluation metrics

A critical limitation is the overreliance on crash statistics as the primary indicator of pedestrian safety. While essential, such metrics fail to capture subjective safety perceptions, behavioural shifts, equity outcomes, or mode shift toward walking. This narrow evaluative lens neglects broader public health, social justice, and mobility goals, which are increasingly central to contemporary urban planning. A more multidimensional approach integrating walkability indices, perceived safety, and access equity is needed to assess the long-term, systemic impacts of interventions.

Limited focus on vulnerable groups and intersectionality

Studies often lack disaggregated analyses by age, gender, ability, or income level. Vulnerable road users such as children, the elderly, and persons with disabilities face distinct risks and mobility constraints that generic interventions may fail to address. Similarly, gender-based concerns related to harassment or social norms are rarely integrated into pedestrian safety research. The lack of intersectional analysis limits the inclusivity and effectiveness of current recommendations.

Neglect of certain safe system components

While pedestrian-focused intervention studies address Safe Roads, Safe Speeds, and Safe People, there is comparatively less attention other pillars of the Safe System, Safe Vehicles and Post-Crash Care. For example, motor vehicle design standards aimed at reducing pedestrian injury severity, or the role of emergency medical systems in mitigating fatality rates, are seldom evaluated alongside infrastructure changes.

By critically evaluating the reviewed literature and systematically identifying these gaps, this review contributes a transparent and policy-relevant synthesis as summarised in the Table 4. Our framework clarifies where future research is most needed and underscores the importance of transdisciplinary, equity-focused, and context-aware approaches in pedestrian safety planning.

Study strengths and limitations

Like all systematic literature reviews, the key strength of this study is the systematic and replicable approach to literature screening and feature extraction. In addition, by using a structured screener matrix and applying PCA, we provide both a granular and holistic view of the evidence landscape. Another strength is the use of principal component analysis to distil complex, multidimensional data into interpretable components. This approach helps identify clusters of interventions that tend to co-occur in the literature, offering new insights into how different safety features may interact or reinforce each other.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the screener matrix relies on the presence or absence of support for each feature as reported in the literature, which may not capture the full nuance or context of each intervention. The binary coding (even with visual enhancements) does not reflect the strength or quality of evidence, nor does it account for variations in study design or outcome measures. Second, the review is limited to studies indexed in the included Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, TRID (Transport Research International Documentation), ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases and published in English, which may introduce selection bias and limit the generalisability of the findings. Third, the PCA is based on a synthesised feature matrix due to the lack of detailed manual annotation for each paper. While this provides a useful demonstration, future work should aim to extract more granular data on intervention effectiveness and contextual factors.

Policy recommendations include:

Integrate pedestrian safety into urban design standards

Urban planners need to embed pedestrian safety principles into land-use and street design guidelines. This includes providing continuous, well-maintained footpaths, pedestrian-only zones, adequate lighting, and clear signage to ensure a safe and accessible walking environment.

Implement traffic calming measures in high-risk areas

Policymakers need to promote the use of traffic calming interventions (i.e., speed humps, raised crosswalks, narrowed lanes, pedestrian refuge islands), especially in residential and school zones, to reduce vehicle speeds and enhance pedestrian safety.

Awareness campaigns and traffic enforcement

Launching public awareness campaigns about pedestrian rights, safe road behaviour, and penalties for violations can shift public attitudes toward safer practices. Simultaneously, strict enforcement of traffic laws (i.e., speed limits, yielding at crosswalks, illegal parking restrictions) are essential to deter unsafe driving behaviours.

Use data-driven tools for identifying and addressing risk

Adopt GIS-based crash mapping, pedestrian volume studies, and safety audits to identify high-risk corridors. Evidence-based planning allows for targeted interventions and efficient allocation of resources for maximum impact.

Promote inclusive design for vulnerable users

Planners must consider the needs of children, the elderly, and persons with disabilities by ensuring features such as tactile paving, audible signals, curb ramps, and benches. Inclusive infrastructure enhances safety and encourages walking among all groups.

Institutionalise pedestrian safety in policy and governance

Policymakers need to mandate pedestrian safety audits, establish dedicated agencies or units within urban local bodies, and include safety goals in mobility and transport master plans to ensure long-term commitment and coordination across departments.

Germany’s FeGiS project in Europe is all about finding dangerous road areas early on. This supports the EU’s Vision Zero goal of having no deaths by 2050. New Zealand’s Road to Zero (2020) focused on lowering speeds and adding safety features. Australia and New Zealand also help by using Austroads’ Keeping People Safe When Walking reports, which combine evidence on pedestrian safety, weaknesses, the effects of crashes, micromobility, and vehicle technology to make recommendations based on systems. Even with these efforts, many people still die while walking, especially those who are more likely to be hurt. This review moves the field forward by using new data, looking at how well policies work, finding gaps, and suggesting specific actions to make pedestrian safety plans for vulnerable road users.

This study advances the understanding of pedestrian safety interventions by systematically mapping the evidence and applying advanced analytical techniques. The findings reinforce the value of integrated, evidence-based approaches and provide a foundation for future research and policy development.

Conclusions

This systematic review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the top 92 research papers and policy documents on pedestrian safety, mapping the support for key safety features across the literature. Interventions such as pedestrian signals, speed enforcement, and urban design modifications are most frequently supported, highlighting the importance of multifaceted strategies in improving pedestrian safety outcomes. The evidence base is multidimensional, with several clusters of interventions contributing to overall safety.

The review confirms the hypothesis that no single intervention is sufficient; rather, a combination of engineering, enforcement, and educational measures is necessary to achieve meaningful reductions in pedestrian injuries and fatalities. This finding is consistent with previous work and underscores the need for integrated approaches in policy and practice.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the constructive feedback from the anonymous reviewers who helped in making this review paper.

AI tools

ChatGPT, 4.0 was used to improve English expression and clarity.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed equally in the research.

Funding

No Funding for this research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.