Glossary

ADDIE Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation model

CVI Content Validity Index

SCT Social Cognitive Theory

TPB Theory of Planned Behaviour

Introduction

Road safety remains a critical global issue, with young people disproportionately affected. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), road traffic injuries rank among the top causes of death for youth worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries with rising motorisation (WHO, 2023) Contributing factors include lax traffic law enforcement, poor vehicle maintenance, hazardous road conditions, human error and limited safety education (Rolison et al., 2018; Setyowati et al., 2024b, 2025). In Indonesia, driver error contributes to about 75 percent of all traffic crashes and results in over 28,000 fatalities (Badan Pusat Statistik, 2021) and places the nation among the top five globally for traffic-related deaths (Erviana et al., 2024). Although national road safety campaigns exist, novice riders, including university students, remain at high risk, often due to limited riding experience and insufficient practical safety education. This highlights the critical need for tailored interventions specifically targeting young riders, addressing knowledge gaps as well as motivational and behavioural factors influencing their riding behaviour.

Despite having foundational knowledge of safe riding principles, studies reveal that awareness does not consistently translate into safe behaviours (Helal et al., 2018; Setyowati et al., 2024a). For instance, in Malaysia, although many students received prior instruction, only 23 percent could accurately interpret basic traffic signs (Abd Rahman et al., 2021) and while revised modules enhanced knowledge, this failed to affect perceived behavioural control (H. N. Ismail et al., 2019). Further, in Denmark, school-based safety programs increased awareness but did not yield noticeable behavioural changes (Bojesen & Rayce, 2020). These findings suggest that knowledge alone may be insufficient and that interventions should actively address psychological factors such as attitudes and perceived control and incorporate cultural dimensions. Culturally sensitive, theory-based interventions hold promise in increasing safe behaviours. Peer-led programs in India reported substantial reductions in risky riding when relatable role models were involved (Masilamani et al., 2022).

Building on these insights, this study introduces “Driving Intervention NAvigation (DINA), Hello, Awareness, Look, Obey (HALO) SAFETY”. The next will be called “DINA HALO SAFETY,” a model anchored in the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). TPB posits that behavioural intentions are influenced by attitudes toward behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, whereas SCT emphasises observational learning, self-efficacy, and reciprocal determinism as motivators of behaviour change (Keffane, 2021). By stressing attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, and integrating observational learning through culturally resonant role models, “DINA HALO SAFETY” is an immersive, behaviour-focused approach that uses culturally resonant multimedia and influencers to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practice (Bakhtari Aghdam et al., 2020; Swetha et al., 2021).

The aims of this study were to: 1) develop an interactive, video-based educational model suited to Indonesian university contexts; 2) validate its effectiveness in improving road safety awareness and behaviours, and; 3) identify the key elements that foster meaningful change (e.g., cultural relevance, influencer participation).

Methods

This research employed a comprehensive research and development design using the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (ADDIE) model. The ADDIE framework was chosen for its iterative nature, ensuring continuous alignment with learning outcomes (Boateng et al., 2018). Participants were undergraduate university students and a panel of five experts.

Recruitment and participants

Participants were recruited from undergraduate students at a Public University in Central Java, Indonesia via official university channels, including faculty emails, WhatsApp student groups, and campus notice boards. Proportional stratified sampling ensured representation across gender, age, and faculties. Inclusion criteria included: (i) active undergraduate status at the university, (ii) holding or intending to obtain a motorcycle licence, and (iii) willingness to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: (i) students with prior formal road safety training courses in the last 12 months, and (ii) students with physical conditions that prevented them from motorcycle riding. Participants were selected through proportional stratified sampling from various faculties to ensure representativeness. Survey respondents (n=416) were drawn proportionally from all university faculties. The focus group participants (n=21) were a subset of the larger survey cohort and were purposively selected to represent gender, age, and faculty diversity. They were divided into two groups (Group A: 10 participants, Group B: 11 participants) to ensure manageable discussion dynamics. Pilot testing participants (n=32) were recruited from a single study program at a different university (outside the 416 respondents) via WhatsApp groups of student organisations. The pilot testing phase served to evaluate the content validity and clarity of the instruments while also ensuring that the main research sample remained uncontaminated by avoiding the use of the exact location or respondents.

Experts were identified through professional associations, prior collaborations in road safety projects, and publication records. Selection was based on inclusion criteria: (i) ≥5 years of professional experience in road safety, health promotion, or educational media, (ii) at least two peer-reviewed publications in their field, and (iii) recognised contributions to traffic safety programs years of experience in road safety, health promotion, or educational media, and recognised contributions to road safety (Candelaria Martínez et al., 2022; Lau et al., 2019; Nagelli et al., 2023; Rahmad & Teng, 2020; Tan et al., 2024). Invitations were sent via email to ten eligible experts, and five accepted: three road safety specialists, one health promotion expert, and one educational media specialist.

ADDIE model

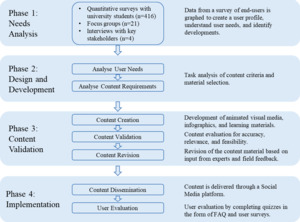

The ADDIE model comprised three primary phases, needs analysis, design and development and, validation and pilot testing.

Phase 1: Needs analysis

A rigorous mixed-methods assessment was conducted to pinpoint critical road safety issues among undergraduate students. A researcher-developed and expert-validated 35-item questionnaire measured students’ knowledge, attitudes, behaviours, and preferred delivery methods of the “DINA HALO SAFETY” content. The sample size (n=416) was determined through a-priori power analysis to ensure statistical robustness (95% confidence level). Responses to both closed- and open-ended questions provided comprehensive insights. Additionally, a focus group discussion was conducted with students purposively selected to ensure representation across gender, age, and faculty backgrounds (n=21). Additional semi-structured interviews were conducted to investigate current curricular gaps with university officials, traffic authorities, and safety riding specialists (n=4). Survey data were analysed in SPSS (Version 26) using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulations. Qualitative data, transcripts from the focus groups and interview, underwent thematic analysis in NVIVO Plus 20. Methodological triangulation was applied to improve internal validity and reduce potential biases associated with self-reported data (Boateng et al., 2018; Kishore et al., 2021).

Phase 2: Model design and development

A multidisciplinary expert panel consisting of five road safety specialists, health promotion experts, and educational media designers reviewed the initial “DINA HALO SAFETY” design. Psychological theories, including the TPB and SCT, were integrated to promote behavioural change by targeting attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control (H. N. Ismail et al., 2019).

The model comprised eight short videos addressing key road safety principles, such as personal protective equipment (PPE), vehicle inspections, and defensive riding, using culturally resonant Gen Z language. Materials included detailed storyboards mapping educational objectives, multimedia production using Camtasia, Canva, and Alight Motion, and iterative script refinement based on expert and user feedback. Subtitles and alternative text descriptions ensured accessibility for users with hearing impairments (Choi & Ahn, 2021).

The “DINA HALO SAFETY” video series covers essential topics like PPE usage, vehicle checks, and strategies to avoid high-risk riding. Examples include “Gear Up, Gen Z!” and “11 Safety Check Steps Before Gaspol,” which deliver concise tips through appealing, culturally resonant content (Figure 1). Following the ADDIE framework analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation expert input and theoretical alignment were systematically integrated. Videos last about 1.5 minutes, reflecting global support for brief, digital learning resources (Zulkifli et al., 2021).

Phase 3: Content Validation and Pilot Testing

Content validation involved a systematic evaluation by the expert panel (n=5). The experts employed the Content Validity Index (CVI) to assess videos for relevance, clarity, graphic media effectiveness, and educational impact (Boateng et al., 2018; Kishore et al., 2021). Videos scoring above 0.79 were accepted, videos that scored between 0.7 and 0.79 were revised, and videos that scored below 0.7 were eliminated (Tan et al., 2024; Wan Mohamad Darani et al., 2024). Videos that scored 0.8 were considered highly valid; while videos that scored under 0.7 were substantially modified (Rooha et al., 2023; Shuhaimi et al., 2023). Expert feedback prompted multiple iterative refinements in video design and content clarity.

For pilot testing, university students (n=32) viewed the revised videos and completed a post-viewing survey measuring clarity, relevance, and potential behavioural impact mapped to TPB constructs (H. N. Ismail et al., 2019). Descriptive statistics and repeated measures t-tests examined pre- and post-viewing scores, focusing on attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. Open-ended questions yielded suggestions for real-life riding examples and culturally resonant testimonials, prompting final edits for video enhancement. The final videos attained an average S-CVI of 0.82 and scored 0.83 for engagement.

Results

Respondents and Informant Characteristics

Across all phases of the study, respondents were evenly represented by gender (female: 50.2%; male: 49.8%) with some variation in individual phases. In the focus groups, most participants were: female (57.1%); aged 20-21 years, and; students at the Faculty of Public Health (57.1%). In the survey of university students (n=416) conducted as the first step, the gender distribution was nearly equal (female: 50.2%; male: 49.8%), the average age was 20 years (SD = 0.99) and, most participants had a licence to ride a motorcycle (86.3%), This suggests that the sample was representative of university students who frequently drive and are at risk of unsafe riding behaviours. Survey respondents were most commonly from Engineering (18.5%) and the Vocational School (13.5%)

From the survey responses, social media was identified as the preferred platform for receiving road safety information, particularly Instagram (60.8%), followed by socialisation (defined as peer discussions, campus seminars, and safety workshops) (56.0%). Table 1 displays the demographic details and information sources.

Needs analysis

A comprehensive assessment of developing the “DINA HALO SAFETY” road safety education model was conducted through both quantitative and qualitative data. Findings, presented in Table 2, highlight significant road safety knowledge gaps. For instance, almost all participants (98.1%) lacked knowledge regarding the necessity of using PPE when riding a motorcycle or conducting pre-riding safety checks, demonstrating a substantial deficiency in road safety awareness. Short educational videos were the preferred medium by most respondents (91.6%). Although social media platforms were considered vital for disseminating educational content (98.8% acknowledged social media’s importance), only 65.6 percent reported actively engaging with such content, underscoring the need for strategies to increase audience retention and interaction. These findings further reinforce the importance of incorporating psychological and behavioural elements into educational interventions to enhance user engagement and effectiveness.

Insights from the focus group discussions confirmed a preference for brief, visually captivating, and culturally relatable content. Most participants favoured having content presented by relatable influencers (96.2%) and safety messages delivered by law enforcement (76.7%) officers to enhance credibility.

One participant noted, “Seeing someone like me talk about road safety makes it easier to connect with the message,” reinforcing the importance of using peer-driven, relatable communication strategies. Humour, real-life examples, and interactive formats were cited as effective engagement methods, in line with global findings on successful road safety campaigns (Masilamani et al., 2022). Table 2 integrates the survey results with focus group perspectives to guide the “DINA HALO SAFETY” model’s conceptualisation.

Model Design and Development

Based on these findings, the “DINA HALO SAFETY” model encompasses eight concise, interactive educational videos addressing key road safety topics, such as PPE usage, vehicle checks, and defensive riding. Scripts were composed in Indonesian using contextually relevant language tailored to university students, ensuring both cultural resonance and accessibility. Animations, voiceovers, and familiar scenarios were integrated, and each video was limited to approximately 90 seconds to maximise engagement and knowledge retention. To enhance inclusivity, subtitles and alternative text descriptions were incorporated, ensuring accessibility for users with hearing impairments.

Final videos were publicly accessible through Instagram, with average video lengths of approximately 90 seconds each, aligning with optimal user engagement recommendations. Table 3 provides an overview of topics, intended learning outcomes, and specific video content in the “DINA HALO SAFETY” series.

Figure 2 illustrates the iterative approach involving initial analysis, expert and user feedback, and continuous improvements to optimise the educational quality and engagement of the “DINA HALO SAFETY” model.

Table 4 emphasises the iterative refinements made to each video, incorporating specific recommendations from both expert reviewers and student users, thereby enhancing overall clarity, effectiveness, and user engagement.

Content Validation and Pilot Testing

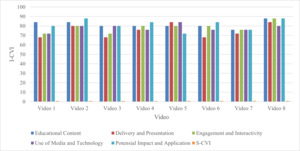

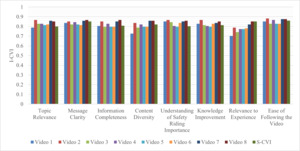

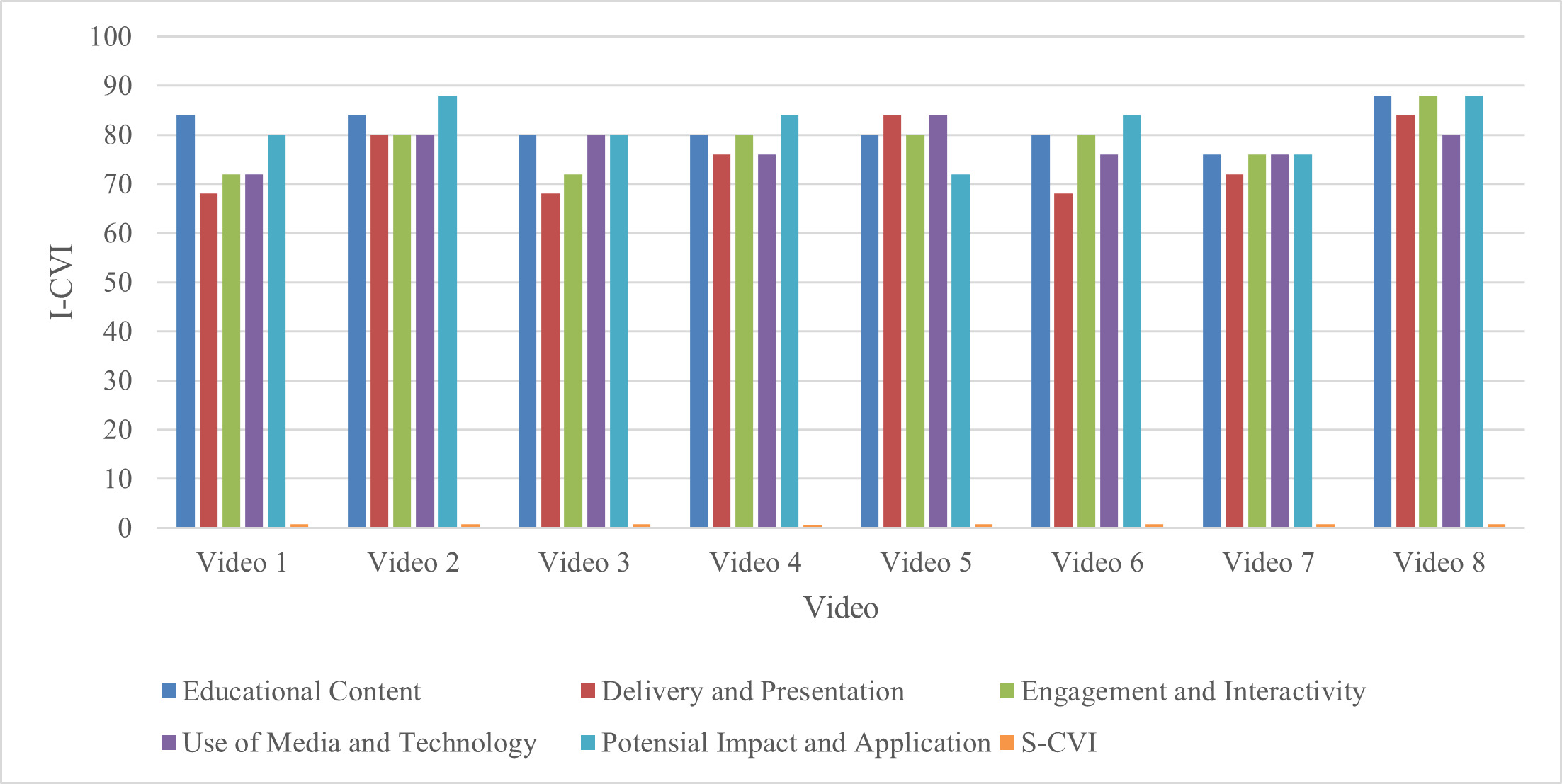

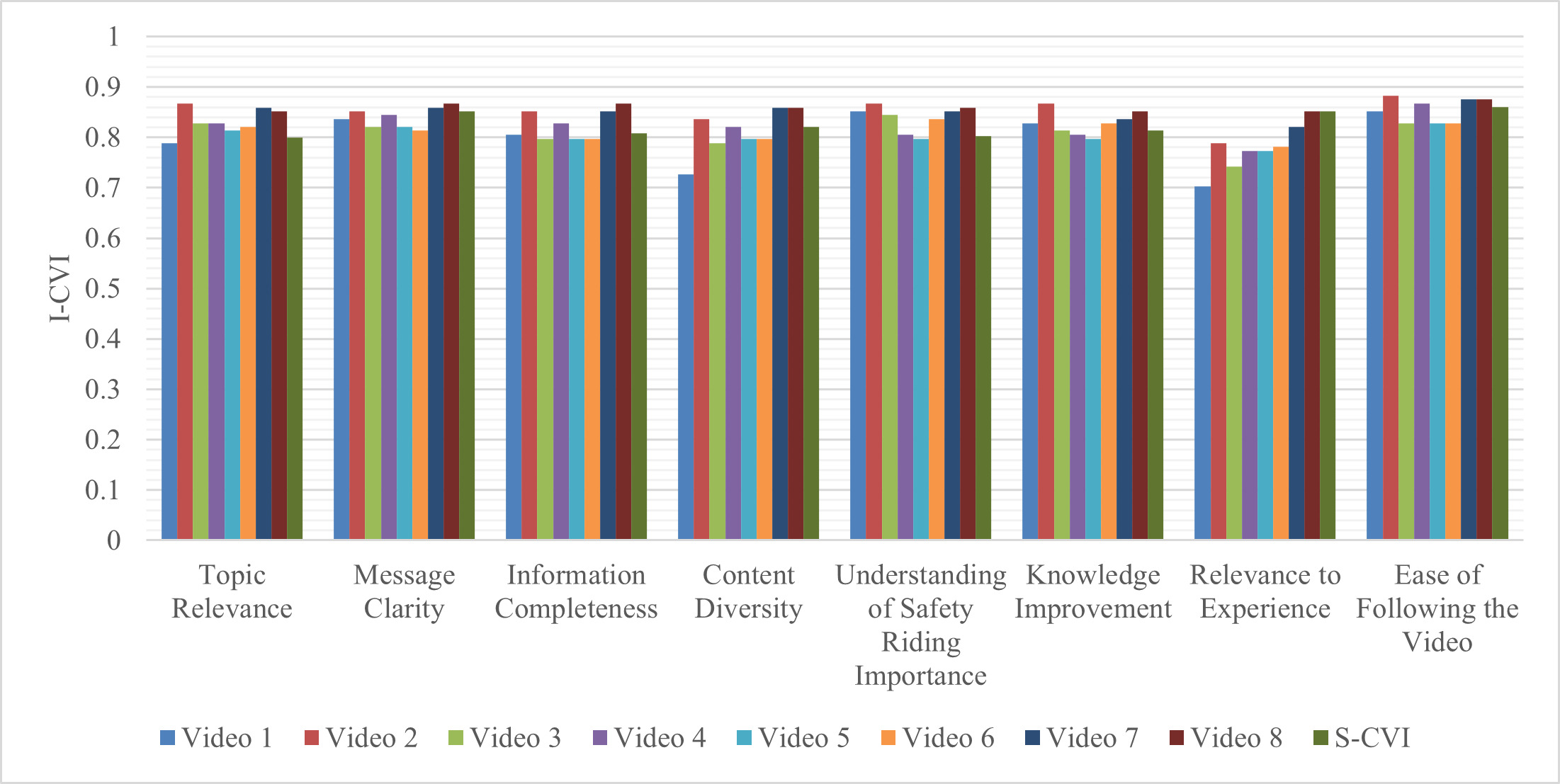

An expert panel (n=5) evaluated each video for educational quality, clarity, and engagement effectiveness using a 5-point Likert Scale (CVI). Videos that scored above 0.79 were deemed valid, while those below 0.7 required major revisions. Minor enhancements, such as adding clarified subtitles, improved graphics, and enhanced animation quality, were recommended to improve viewer engagement. Figure 3 shows the expert panel scores. Overall, videos achieved an average CVI score of 0.82, indicating strong validity. The highest-rated video was S-CVI (0.82), whereas others (e.g., Videos 1 and 4) needed minor revisions.

To meet best practices in education validation (Boateng et al., 2018; Kishore et al., 2021), User Engagement Assessment (face validity) was conducted among university students (n=32). The average S-CVI was 0.82, with individual scores ranging from 0.79-0.86. Videos scoring below 0.79 underwent targeted enhancements, including content restructuring, refinement of voiceovers, and improved visual consistency to enhance clarity and accessibility.

Pilot testing results demonstrated that the videos significantly improved participants’ road safety knowledge and strengthened their intent to adopt safe riding behaviours. As presented in Figure 4, overall engagement metrics were high (over 81%) while Video 7 and Video 8 were particularly effective in influencing behavioural change. Although the pilot sample was limited to a single university, the findings suggest strong potential for wider application. Future studies should explicitly employ multi-institutional validation methods, longitudinal tracking to assess the sustainability of behavioural changes, and include objective measures such as on-road observations or telematics data to enhance validity beyond self-reported data.

Behavioural changes and engagement

Quantitative data identified that the “DINA HALO SAFETY” videos demonstrated improvements in road safety awareness and increased participants’ self-reported readiness to consistently use PPE and conduct pre-riding vehicle checks (over 90%). Students expressed a distinct preference for brief, highly visual, and interactive learning materials that showed real-world riding scenarios. Culturally relevant, interactive formats have the potential to bridge the gap between knowledge and practice, aligning with behaviour change research (H. N. Ismail et al., 2019). Future research should specifically investigate whether similar culturally tailored and interactive interventions are equally effective across diverse geographic and socio-economic populations through longitudinal follow-up assessments.

Discussion

Needs analysis

Technological advancements, particularly the widespread use of internet-connected mobile devices and social media, have significantly expanded how information is disseminated across diverse demographics and regions. In 2024, social media use exceeded five billion users, with projections surpassing six billion by 2028, highlighting its cost-effectiveness and scalability for road safety campaigns (Statista, 2024). Defined as online platforms where users share information, opinions, and knowledge through interactive media, social media is particularly well-suited for targeted educational campaigns aimed at university students, who are highly reliant on these platforms for both communication and information (Stellefson et al., 2020). Nonetheless, while social media provides an effective distribution channel, ensuring both engagement and consistent behavioural change requires strategically designed content, informed by behavioural theories, and periodic reinforcement across multiple institutions and diverse user profiles.

Based on Table 2, this study’s findings are in line with global trends, showing that students most often preferred Instagram (93.5%) and TikTok (90.6%) as platforms for receiving educational content. Similar research in Malaysia, Egypt and the United States underscores digital platform effectiveness for road safety education (Anderson et al., 2023; Fattori, 2021; Ghahramani et al., 2022; Witte et al., 2024). However, only two thirds reported engaging with existing materials, suggesting a strong need for interactive and relatable content.

Participants lacked essential knowledge on proper PPE and vehicle checks, expressing a preference for short videos and relatable influencers an approach validated in previous studies, including peer-led initiatives in India (Masilamani et al., 2022; Schreiner et al., 2021). While printed materials maintain some value, they are most effective when supplementing online campaigns. Further emphasising cross-sector collaboration, including partnerships with traffic authorities, educational institutions, and local communities, could significantly reinforce dissemination efforts and extend the model’s impact.

Model design and development

Road safety education is often called for integration into formal curricula (N. K. Ismail et al., 2023; Odame et al., 2024). The “DINA HALO SAFETY” model incorporates TPB constructs attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control to enhance both knowledge and behavioural intent. Unlike traditional information-only methods, this model uses interactive videos specifically adapted for Indonesian university students. Additionally, integrating SCT elements such as observational learning and self-efficacy through culturally resonant scenarios and relatable influencers enhances the model’s potential effectiveness. By leveraging TPB elements (including animations and culturally familiar scenarios), the model bridges the gap between awareness and actual behaviour, mirroring successful outcomes observed in Iran and Denmark (Bakhtari Aghdam et al., 2020; Keffane, 2021). Humour, relatable language, and relevant context further promote engagement, echoing positive experiences from peer-led programs in India (Schreiner et al., 2021). However, additional research is needed to determine whether the same culturally adapted approach would be equally effective in different educational contexts, particularly in rural or underprivileged regions where access to digital learning resources may be limited. Future evaluations should include mixed-method approaches with direct behavioural observations to measure real-world impact accurately.

Validation and pilot testing

Findings from this study offer a valuable foundation for future studies to expand sample diversity and extend testing durations for greater external validity (Boateng et al., 2018; Kishore et al., 2021). Validating educational media in road safety ensures effectiveness. Expert evaluations of the “DINA HALO SAFETY” videos showed strong scores in relevance, presentation, and engagement, (Video 6: 0.86) and an S-CVI of 0.82, indicating readiness for deployment with other videos needing only minor adjustments (Video 2: 0.82; Video 8: 0.80). These validation steps address practicality and sustainability, aligning with recommended educational intervention standards (Boateng et al., 2018; Kishore et al., 2021). Despite these strong validation metrics, further rigorous evaluation using longitudinal designs and larger, diverse samples is crucial to verify the intervention’s sustained impact and generalisability across different contexts.

User feedback emphasised clarity and topical significance, with pilot data revealing improved knowledge retention and higher behavioural intent findings consistent with research showing the superiority of engaging, theory-based materials over traditional methods (Domala et al., 2023; Purcell & Romijn, 2020; Wang et al., 2018; Zulkifli et al., 2021). However, the small sample size and brief observation period limit confirmation of enduring impacts, consistent with global observations that effects often wane without ongoing support (Modipa et al., 2022). Future studies should address these limitations by incorporating larger participant groups, longitudinal data collection, and objective measurements to verify sustained behavioural changes over time.

Study strengths and limitations

This study’s primary strength lies in its integration of robust theoretical frameworks, specifically the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Social Cognitive Theory, with culturally tailored multimedia to foster practical, lasting behaviour change. By leveraging social media platforms and concise, engaging videos, the “DINA HALO SAFETY” model addresses the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world riding practices, which is often missed by traditional road safety education. Further, the user-centred design encompassing expert feedback and pilot testing ensures relevance and potential scalability to broader student populations.

However, several limitations circumscribe the broader applicability of these findings. First, the reliance on a single university context constrains generalisability, underscoring the necessity for future inquiries to engage larger, randomised cohorts across multiple institutions and sociocultural environments. Second, although the intervention yielded encouraging short-term outcomes, its long-term efficacy remains indeterminate. Extended interventions accompanied by longitudinal follow-up assessments are required to ascertain the persistence of behavioural change and to evaluate engagement across varying contexts. Third, the present model does not incorporate immersive modalities such as augmented or virtual reality, which may substantially enhance both learner engagement and cognitive retention. Finally, the exclusive dependence on self-reported measures introduces the possibility of reporting bias. Future research should therefore integrate objective indicators of riding behaviour, such as telematics data or direct field observations, to reinforce the validity of the outcomes. Taken together, subsequent studies should prioritise multi-institutional collaborations, longitudinal research designs, and the incorporation of objective behavioural metrics in order to strengthen external validity and advance cross-cultural applicability.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the validated “DINA HALO SAFETY” model shows promise in boosting road safety awareness and shaping safer riding behaviours among university students by merging the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Social Cognitive Theory with culturally relevant, interactive content. While initial findings are encouraging, further studies must validate its long-term impact, especially given the limitations associated with self-reported measures and the pilot’s single-institution focus. Broader trials spanning multiple institutions, socio-economic groups, and regions will be vital for assessing external validity and refining the model’s adaptability. Social media emerges as a cost-effective, scalable platform, capitalising on digital trends to engage young motorcycle riders. Yet, sustaining participation over time remains challenging, suggesting the need for periodic content updates, gamification features, and reinforcement strategies. Policymakers and educators could integrate “DINA HALO SAFETY” into formal curricula, while emphasising strategic partnerships with influencers, educational institutions, traffic enforcement agencies, and NGOs to significantly amplify the program’s reach and effectiveness.

Further strengthening evidence of enduring behavioural change requires objective performance metrics, such as telematics or direct observation, along with longitudinal follow-ups. Incorporating augmented or virtual reality, as well as AI-driven learning modules, could enhance interactivity and retention. Future studies should explicitly detail methodologies for longitudinal assessments and cross-sector collaborations to establish robust, generalisable evidence of the model’s sustained effectiveness and real-world applicability.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all participants, experts, and institutions involved in developing and validating the “DINA HALO SAFETY” educational model.

AI tools

The AI tool ChatGPT 4.0 was used to improve English expression and clarity.

Author contributions

Dina Lusiana Setyowati: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Investigation; Validation; Data Curation; Formal Analysis; Writing – Original Draft; Visualisation; Project Administration; Writing-Review & editing. Yuliani Setyaningsih: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Validation; Writing – Review & Editing; Supervision. Chriswardani Suryawati: Validation; Writing – Review & Editing; Supervision. Daru Lestantyo: Validation; Writing – Review & Editing; Supervision. Robiana Modjo: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Validation.

Funding

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of Indonesia supported this work through the Indonesian Education Scholarship, Center for Education Funding and Assessment, and Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education under contract number [202209090761].

Human Research Ethics Review

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health, Diponegoro University (Number: 615/EA/KEPK-FKM/2023).

Data availability statement

Data used for this project are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author

Conflicts of interest

The authors declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Translations, Top row: Did you know that every year; Safe navigation on campus, obey traffic signs; Increase our self-efficacy for safe driving. Bottom row: Let’s recognise and avoid it; Stay cool but safe, safe distance and speed limits; Gear up, Gen Z! Traveling must be safe; Safety check steps before going full throttle, Gen Z friends