Introduction

Road safety is a critical global public health and development issue, with developing countries facing particularly acute challenges with approximately 1.19 million annual deaths due to road traffic crashes globally, with an additional 20-50 million people suffering non-fatal injuries (WHO, 2023). In Ecuador, the situation is particularly dire. Injuries from road traffic crashes are the fifth leading cause of death and the second cause for individuals aged 5-29 years (INEC, 2024). In 2021, the fatality rate from road crashes in Ecuador was 23.4 deaths per 100,000 people which exceeds the rates of neighbouring countries, Colombia (16.2) and Peru (12.7), and was more than five times higher than the rate in Australia (4.5) (WHO, 2021).

These statistics underscore an urgent need for comprehensive reforms in the approach to road safety in Ecuador. Human error is a significant contributing factor to road crashes both globally (WHO, 2023). In Ecuador, the types of human factors identified as contributing to crashes include: driver errors, distracted driving, speeding, disregarding traffic signals, tailgating and driving under the influence (ANT, 2023). As Lonero et al. (1998) emphasised, driver licences are more than mere permits; they validate a person’s competence to drive safely on public roads. While driver behaviour – such as speeding, distraction, and alcohol/drug impairment – was identified as a major contributing factor, these behaviours occur within a broader system shaped by infrastructure design, road conditions, and enforcement of safety policies. Addressing road safety thus requires not only targeting driver behaviour but also systemic measures such as safer road designs, appropriate speed limits, and enhanced monitoring systems.

Currently in Ecuador, the licensing system has two main options: ‘professional’ and ‘non-professional’. The term ‘non-professional’ refers to regular drivers who do not receive the extensive training required for professional drivers (e.g. people driving taxis and buses). The non-professional licensing system includes three types of licences, all of which can be obtained through non-professional driving schools:

-

Licence Type A: for motorcycles, mopeds, quads, and tricycles

-

Licence Type B: for cars, vans, and vehicles with a Gross Vehicle Weight (GVW) of up to 3,500 kg

-

Licence Type F: for vehicles adapted for people with physical disabilities

The current driver education curriculum for these non-professional licences mandates a 34-hour program (Reglamento de Escuelas de Formación, Capacitación y Entrenamiento de Conductores No Profesionales, 2022). This compares to requirements in the United States of America (USA), where most states mandate 30 hours of classroom instruction, with some offering online or parent-taught options (Thomas et al., 2012).

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of initial driver licensing program components across selected countries, illustrating that while the total duration of the program in Ecuador is similar to some countries, it falls short of more comprehensive systems. For example, Australia has a well-established and comprehensive graduated licensing system, known for its rigorous requirements and proven effectiveness in enhancing road safety. Victoria was specifically chosen for comparison as it is one of the leading states in implementing this system.

Recognising the inadequacy of the current system and the high crash rates, the Ecuadorian government has proposed extending the driver education requirement to 90 hours (ANT, 2024), consisting of 54 hours of theoretical instruction and 36 hours of practical training. However, the effectiveness of the proposal depends on both the quantity of hours and the quality and diversity of instruction. Research indicates that increased training hours must be accompanied by well-trained instructors who understand the importance of exposing learner drivers to varied driving conditions, situations and environments (Williams & Ferguson, 2002).

International research consistently demonstrates the effectiveness of Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL) systems in reducing crash rates among novice drivers. Studies have shown that GDL programs in some states of USA, Canada and Australia led to average reductions of 15 percent in overall crash rates and 21 percent in injury crashes among 16-year-olds (Russell et al., 2011). In the USA, GDL systems have been associated with an average 11 percent reduction in teen fatalities (Prato, 2009). Similarly, in Queensland, Australia, the implementation of a comprehensive GDL system resulted in a 14 percent reduction in novice driver fatal crashes, particularly in the critical early stages of licensure (Senserrick et al., 2021).

The success of GDL systems is attributed to their structured approach, which typically includes extended supervised learning periods followed by provisional or probationary licensing phases. During the provisional phase, when new drivers begin driving independently, protective restrictions are implemented, such as night driving restrictions and limits on young passengers (McKnight & Peck, 2002; Williams & Ferguson, 2002). These restrictions are gradually lifted as drivers gain experience and demonstrate responsible driving behaviours. The Australian Graduate Licensing Scheme (GLS) Policy Framework offers a particularly instructive model, presenting three tiers, standard, enhanced, and exemplar, each designed to progressively improve young driver safety through increasingly comprehensive measures (Walker, 2014).

In response to the road safety challenges in Ecuador, this study proposes a comprehensive Driver Learning System (DLS) that integrates key elements from successful international GDL systems, tailored to local conditions. The DLS introduces a three-stage GDL framework, complemented by initiatives to integrate traffic safety education into schools, update existing driver education programs, and promote continuous learning across all licence categories. Informed by analysis of local crash statistics and driver behaviour studies, the system incorporates modern educational techniques and technologies, including risk awareness training and driving simulators. While the DLS offers significant potential benefits, including reduced traffic crashes and a safety-first driving culture, challenges such as stakeholder resistance and resource investment needs are acknowledged. Nevertheless, this proposal represents a crucial step towards comprehensive reform of driver licensing system in Ecuador, with the potential to significantly improve road safety outcomes.

International trends in driver education

Driver education has evolved significantly in recent years, responding to emerging challenges in safe mobility and the need to cultivate low-risk driving among novice drivers. While traditional approaches to driver education have long been considered essential for road safety, recent research has cast doubt on their effectiveness as standalone interventions (Akbari et al., 2021). This section explores current trends and best practices in driver education globally, highlighting the shift towards more comprehensive, integrated approaches to improving road safety outcomes.

Research on the safety benefits of driver education yielded sceptical results. Early studies showed no significant differences in crash rates between novice drivers who received formal education and those who did not (Williams & Ferguson, 2004). Moreover, some school-based programs may inadvertently increase crash risks among teenagers by encouraging earlier licensing (Roberts & Kwan, 2001). These findings underscore the need for a more nuanced approach to driver education.

Driver education must be grounded in solid research and theories concerning the skills, behaviours, motivations, and risks of young drivers, alongside effective behavioural change principles (Lonero, 2008). Driver education may have the most significant impact on crash rates when combined with GDL systems and other broader social approaches, rather than as a standalone intervention (Shell et al., 2015). The integration of driver education programs with GDL systems has emerged as a promising approach for improving road safety outcomes (Thomas et al., 2012).

The GDL systems have shown considerable success in reducing crash rates among young drivers by limiting their exposure to high-risk situations (Bates et al., 2018). These systems typically involve three stages: learner’s permit; intermediate licence, and; full unrestricted licence. Each stage progressively introduces new drivers to the complexities of driving while minimising the risks associated with inexperience. For example, the learner’s permit stage focuses on supervised practice and emphasises the development of basic driving skills, including night driving, under the guidance of a driver with a full, unrestricted licence (Williams, 2017).

Several key trends have emerged in modern driver education programs:

-

Holistic Approach: there’s a shift towards training approaches that extend beyond technical driving skills. Higher-order driving instruction, which includes elements such as driving plans, surveillance, and situational risk assessment, has been shown to reduce crash risk in young drivers (Watson-Brown et al., 2020). Modern curricula focus on the technical aspects of driving as well as road safety awareness, decision-making skills, stress management, and low-risk driving behaviours.

-

Increased Parental Involvement: research has demonstrated that parental management of the early independent driving experiences of novice teens improves safety outcomes (Simons-Morton & Ouimet, 2006; Zeringue & Laird, 2018) and led to an increased emphasis on involving parents in the driver education process.

-

Educational Technology: the integration of educational technologies is gaining popularity in road safety education. Driving simulators (Alonso et al., 2023; Eichberger et al., 2022), mobile applications, and online learning platforms offer more interactive, realistic, and personalised learning experiences, facilitating safe practice of driving skills in diverse scenarios. PC-based and e-learning alternatives can be partial solutions as they can educate both teenagers and parents (Thomas et al., 2012).

-

Continuous Education: there is growing recognition of the importance of continuing education for drivers to update knowledge, improve skills, and promote safe driving behaviours throughout their lives (Senserrick et al., 2017). Modern curricula include initial training, continuous road safety education programs and refresher courses for experienced drivers (Agre, 2016). For instance, online hazard perception training for novice drivers has been shown to improve crash-risk-related skills, with refresher sessions enhancing long-term benefits (Horswill et al., 2023).

-

Emphasis on Risk Factor Awareness: curricula are increasingly incorporating specific content on risk factors associated with driving, including alcohol and drug use, fatigue, distraction, and speeding (Baker et al., 2012). These programs also focus on strategies for preventing and mitigating associated risks (Yahoodik & Yamani, 2021).

Effective driver education in the modern context should be evidence-based and encompass comprehensive approaches to enhance road safety. The integration of driver education with GDL systems, emphasis on holistic training including parental involvement, utilisation of educational technology, promotion of continuous education, and increased awareness of risk factors all contribute to safer driving behaviours. Coordination between driver education, parental and community influences, and behavioural factors is essential for reducing serious crashes among novice drivers. As the field continues to evolve, these trends are likely to shape the future of driver education initiatives worldwide.

Crash statistics and risk driving behaviour

Road safety is a global concern, with international bodies and national governments setting ambitious targets to reduce traffic-related fatalities and injuries. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals aim to halve the number of deaths and injuries caused by road traffic crashes by 2030 (UN, 2015). Aligning with this global initiative, in Ecuador, the Plan for Development of the New Ecuador targets a reduction in the in-situ mortality rate from road crashes by 0.71 per 100,000 inhabitants between 2023 and 2025 (Secretaría Nacional de Planificación, 2024). Additionally, Ecuador’s National Safe Mobility Strategy aims for a 50 percent reduction in road fatalities by 2030 (MTOP, 2022). These goals reflect a broader international trend, exemplified by the European Union’s “Vision Zero” initiative, which aspires to achieve near-zero fatalities in road transport by 2050 (EU, 2023).

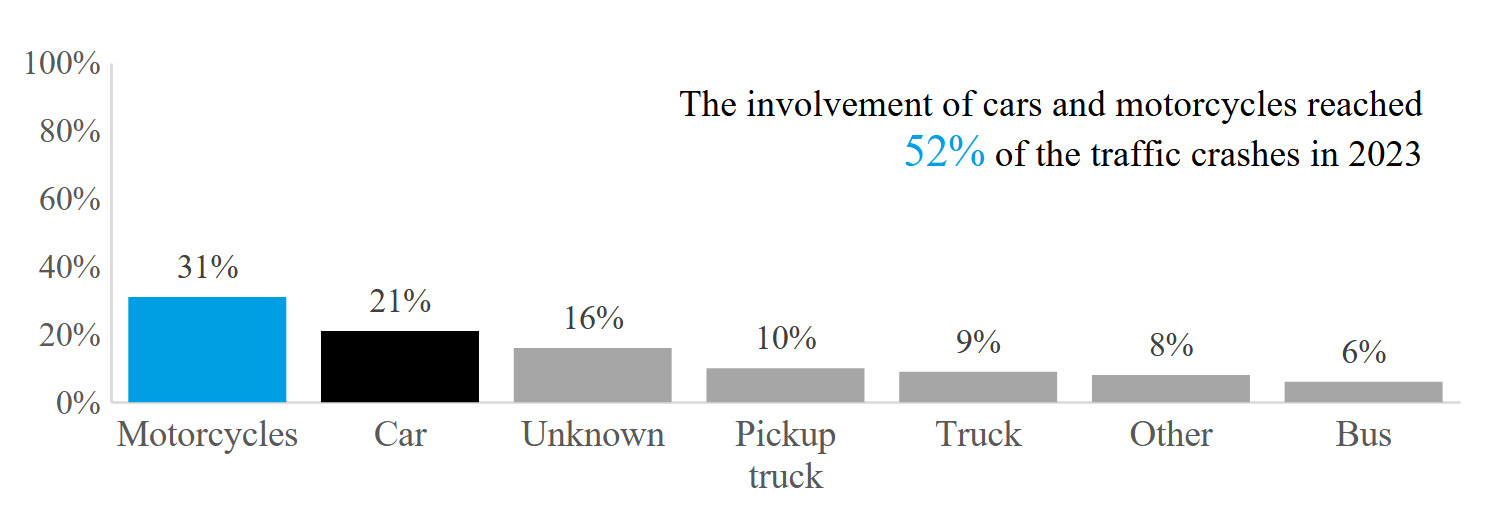

In 2023, Ecuador’s National Transit Agency (ANT) reported 2,373 fatalities due to road crashes (ANT, 2023). From 2017 to 2023, Ecuador has maintained a consistent trend in fatal crashes, with an annual average of 18,588 injuries and 2,112 fatalities due to road crashes (ANT, 2023). Figure 1 highlights that 52 percent of crashes in 2023 involved motorcycles or cars, typically driven by holders of licences A, B, or F.

While there are a range of system factors that contribute to road crashes, driver behaviour is a frequently reported factor (Wu et al., 2014). However, many behaviours are likely to be underreported. For instance, some individuals are fined for not using seat belts, others are not detected. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the road safety situation, it is crucial to complement the analysis of crash statistics with relevant local driver behaviour studies. Several recent studies provide valuable insights into driving practices and challenges specific to Ecuador. Key findings are summarised below:

Seat belt and child restraint use

An observational study (OSEVI-UTPL, 2023) reported that:

-

35% of private vehicle drivers did not use seat belts

-

62% of front-seat passengers and 94% of back-seat passengers did not use seat belts

-

82% of infants and 94% of children were not secured with child restraint systems

The author also reported that 22 percent of drivers used their mobile phones while driving.

A WHO study (2018) reported that for motor vehicle occupants in Ecuador:

-

74% of front-seat occupants did not use a seat belt

-

98% of back-seat passengers did not use a seat belt

-

85% of children were not properly restrained

Traffic light compliance

An observational study conducted in July 2021 (OSEVI-UTPL, 2021) reported drivers and motorcycle riders crossed signalised intersections during:

-

71% the yellow signal phase

-

63% the red signal phase

Traffic violations by licence type B holder

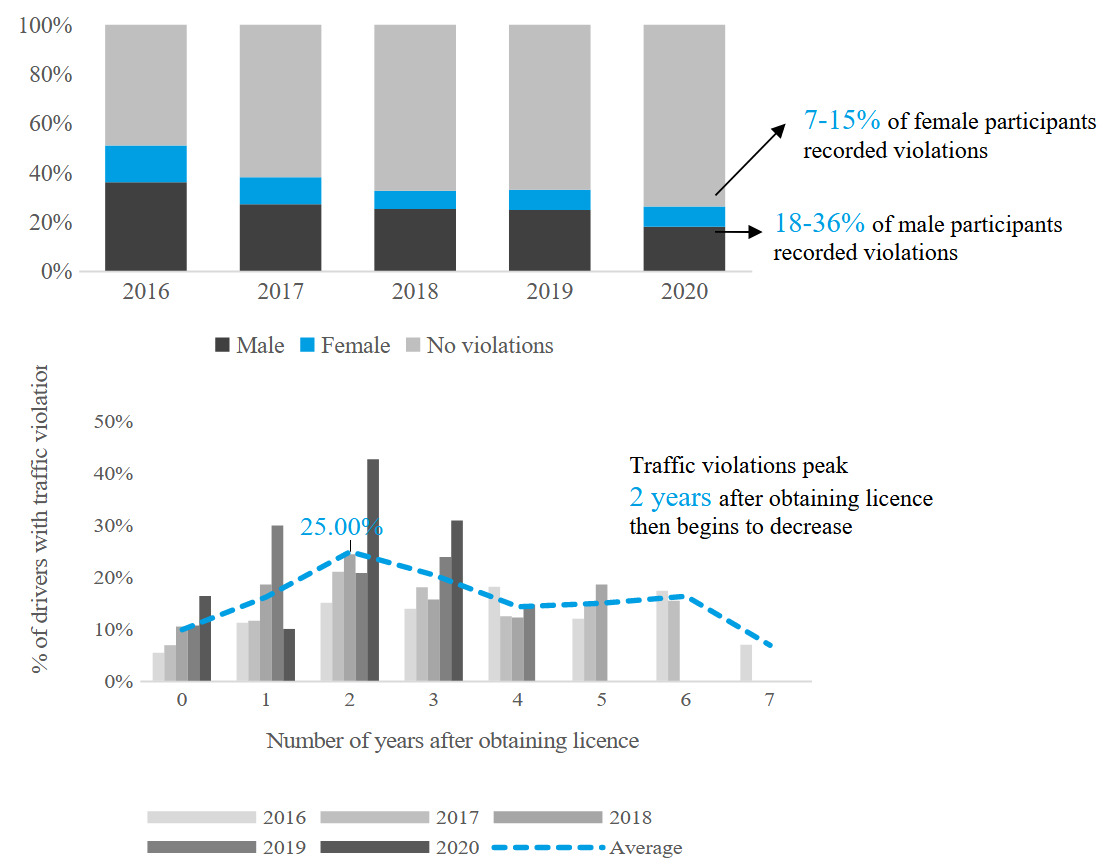

Figure 2 shows the traffic violations by students with licence type B between 2016 and 2020 (García-Ramírez et al., 2024):

-

18-36% of male participants

-

7-15% of female participants

-

Violations peaked two years after obtaining the licence type B and then began to decrease

-

Most frequent violations: not using seat belts, parking in prohibited areas, not transferring vehicle ownership, driving without a valid licence, and exceeding speed limits

Motorcycle driver behaviour

Given the high number of motorcycle riders involved in road crashes, specific studies have been conducted on motorcycle driver behaviour in Ecuador:

Helmet use and safety practices

An observation study (OSEVI-UTPL, 2023) reported:

-

4% of motorcyclists did not use a helmet

-

19% of co-pilots and 60% of passengers did not wear a helmet

-

31-48% of riders who wore helmets did not fasten them properly

-

24% of motorcyclists used a mobile phone while riding

A WHO study (2018) also reported similar behaviour in Ecuador. While most riders wore a helmet (90%), 48-88 percent of passengers did not wear a helmet.

Helmet safety awareness

A study in Loja and Zamora cities (Vásquez-Monteros et al., 2024) revealed:

-

26-31% of respondents wore helmets primarily to avoid fines

-

40-53% lacked awareness of certified helmet safety benefits

-

2-9% considered helmet certification when selecting headgear

-

50-62% of motorcycle riders did not wear additional protective gear

-

40-51% of helmets displayed damage to their outer shell

-

21-25% of retention systems were in satisfactory condition

-

32-34% of examined helmets lacked certification

-

23-41% of helmets were appropriately sized for participants

Traffic violations by licence type A holders

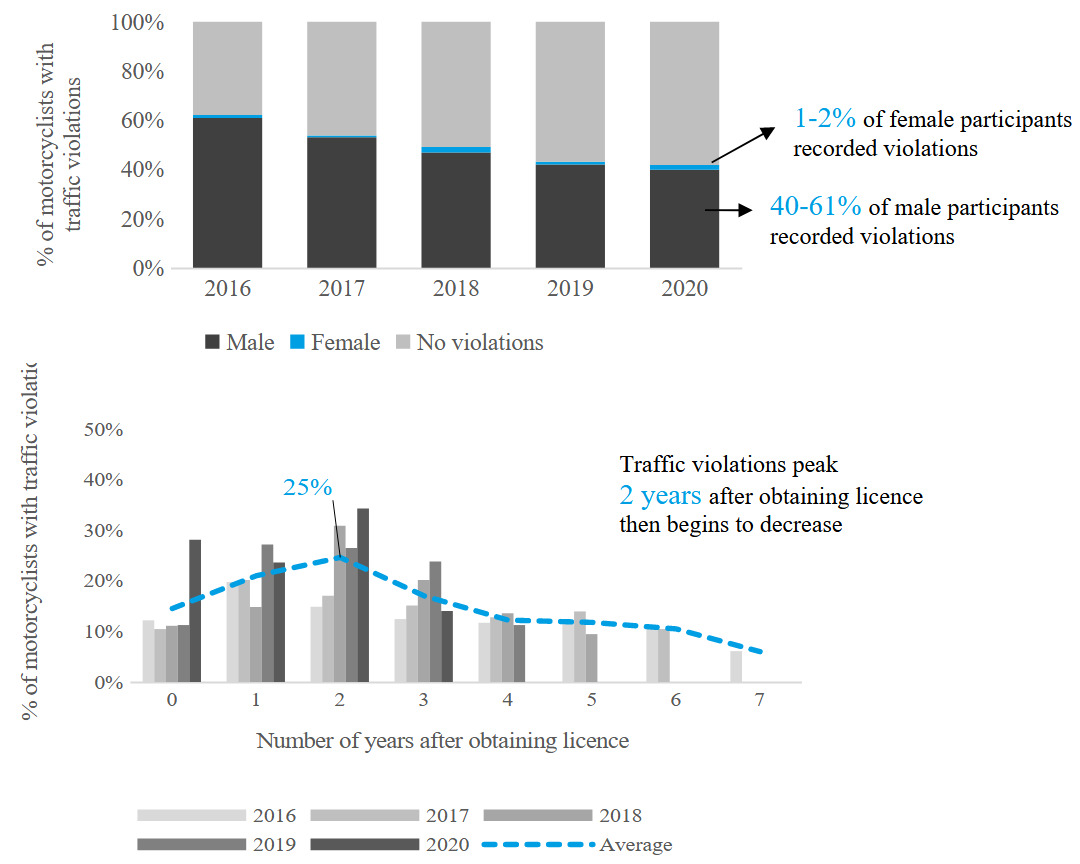

Figure 3 shows the recorded traffic violations among motorcycle riders with the licence type A (García-Ramírez et al., 2024) that reported:

-

40- 61% of male participants had recorded violations

-

1-2% of female participants had recorded violations

-

Violations peaked two years after obtaining the licence and then decreased

-

Most frequent violations: illegal parking, not registering vehicle ownership transfer, and not using approved helmets or reflective clothing

Key findings from driver behaviour studies

While these studies did not identify crash causation, the findings offer crucial insights into concerning driving behaviours in Ecuador and highlight attitudes toward road safety that may influence crash outcomes. For example, in the event of a crash, the lack of safety restraint or helmet use, can significantly increase the likelihood of fatalities or severe injuries. When considered in the international context, four behaviours of road users in Ecuador were of specific concern: lack of seat belt use, lack or misuse of motorcycle helmets, mobile phone using while driving and speeding.

As discussed above, seat belt usage rates in Ecuador are low. In particular, the use of child restraints (18% of infants, 6% of children) are significantly lower than those in Australia (92% use child restraints) (Reeve et al., 2007) and some parts of Colombia (65% in Ibagué) (Rodríguez Hernández et al., 2017). However, seat belt non-compliance may be a bigger issue among South American countries as the seat belt wearing use among front seat occupants (Ecuador: 65% drivers; 38% passengers) was higher than rates reported in Peru (16%) (WHO, 2018).

Motorcycle helmet use by riders in Ecuador (96%) surpasses the use by riders in Peru (70%) (WHO, 2018). However, Ecuador falls short of the near-universal compliance in Bogotá, Colombia (99%) (Guzman et al., 2020) and Australia (99%) (WHO, 2018).

While specific data on distracted driving in Ecuador is limited, the issue of mobile phone use while driving (22%) appears to be a common problem across countries, with reported rates of 37-41% in Australia (Watson-Brown et al., 2024) and 37-58% for texting while driving in Colombia (Arévalo-Tamara et al., 2022).

Both Ecuador and Australia show a pattern of increased violations in the initial years after licensing, particularly among young male drivers (Faulks et al., 2024). This is also evident in neighbouring countries with a significant portion of young Colombian drivers admitting to exceeding speed limits regularly, with many reporting speeds 10-20 km/h over the limit and others exceeding by even more (Oviedo-Trespalacios & Scott-Parker, 2018).

These comparisons highlight that while Ecuador faces significant challenges in road safety behaviours, similar issues exist to varying degrees in other countries. These behaviours, though not always directly linked to crash causation, indicate broader systemic issues in road safety that require intervention. Low compliance in the use of seatbelts and motorcycle helmets reflects broader attitudes toward road safety. The data suggests that Ecuador could benefit from adopting successful strategies implemented in countries with higher compliance rates, particularly in areas such as seat belt and helmet use.

Given these findings, improving road safety in Ecuador requires more than just extending driver training hours. A comprehensive, evidence-based educational framework is needed, one that tackles the specific behavioural challenges identified in Ecuador and also integrates proven strategies from other countries.

Proposal of Driver Learning System (DLS) for Ecuador

It is essential to develop a comprehensive Driver Learning System (DLS) tailored to meet the challenges in Ecuador. The following section outlines a proposal for such a system, designed to address the identified gaps and incorporate successful global strategies adapted to the context in Ecuador.

Foundational traffic safety education

Road safety education cannot be confined to a brief training period before licensing. It is unrealistic to expect that a few hours of instruction can transform an inexperienced adolescent into a mature, low-risk taking driver (Thomas et al., 2012). Instead, road safety must be viewed as a fundamental aspect of civic education, encompassing norms of coexistence and values that should be ingrained within the national education system.

The new traffic law enacted in 2021 (Ley Orgánica de Transporte Terrestre, Tránsito y Seguridad Vial (Quinto Suplemento N°398), 2021) mandates road safety education in both basic and high school, coordinated with the Ministry of Education. However, implementation has been hindered by teachers’ insufficient knowledge and a lack of appropriate academic materials. This gap presents an opportunity to develop comprehensive educational resources, including books, guides, and courses for teachers, students, parents, and other stakeholders in the education system.

While the immediate impact on reducing road crashes may vary, the long-term benefits of a well-implemented DLS are promising, based on evidence from successful GDL systems in other countries and research on the effectiveness of driver education interventions.

3-Stage GDL System

To enhance the learning process and address the concerning trend of traffic violations peaking within the first two years of obtaining a licence, we propose the adoption of a 3-stage GDL system.

Learner’s permit stage

During this initial stage, aspiring drivers and motorcycle riders must complete a comprehensive education and training program covering both theoretical and practical aspects. To obtain a learner’s permit, individuals will be required to pass a written test assessing their knowledge of traffic laws and regulations. The training should include relevant information about local road safety issues and common driving behaviours observed in Ecuador. Key features of this stage would include:

-

Supervision by a licensed adult

-

Restrictions on carrying passengers

-

Minimum holding period of six months

-

Parental involvement through specialised workshops

-

Temporary restrictions on night driving

-

Completion of a written test before progressing to the next stage

Although night driving is restricted during this phase, it is recognised as an essential skill. Therefore, night driving under supervision is strongly encouraged in later stages of the licensing process to ensure drivers develop the necessary experience under controlled conditions.

While parental involvement is critical during the learner’s permit stage, evidence suggests that continued parental supervision and enforcement of restrictions beyond this phase further reduces risky driving behaviours in young novice drivers once they begin driving independently (Simons-Morton & Ouimet, 2006). This ongoing involvement can be facilitated through parental education and the use of monitoring technologies (Curry et al., 2015), ensuring safer driving habits during the early years of independent driving (Taubman-Ben-Ari et al., 2017).

Intermediate licence stage

The intermediate licence stage would require a 30-40 minute road test that focuses on evaluating a driver’s basic competencies and safe driving practices. Candidates would demonstrate their ability to operate a vehicle safely in common driving scenarios, including city streets and highways. The test would assess skills including: proper use of mirrors and turn signals; manoeuvring the motor vehicle (e.g., pulling away from/returning to the kerb, making turns, changing lanes, parallel parking), navigating traffic and potential hazards while complying with road rules, signals, maintaining appropriate speed and following distance. After passing a road test, individuals will progress to the intermediate licence stage.

This phase of licensing which permits unsupervised driving by inexperienced novice drivers is recognised as the riskiest stage. Additional restrictions are necessary to minimise exposure to high-risk situations. These restrictions would include:

-

Limited night driving hours

-

Passenger limits to reduce distractions

-

Alcohol and phone usage are strictly prohibited

-

Minimum holding period of 12 months

Research indicates that novice drivers should avoid high-risk situations such as night driving, driving with teen passengers, using electronic devices, and navigating high-speed or complex roads to develop competence and judgment through experience (Simons-Morton, 2007). While some driving privileges are granted during this stage, the primary focus remains on driver safety through controlled exposure and stringent oversight.

Full unrestricted licence

After successfully completing the intermediate stage, passing an advanced road test, and maintaining a clean driving record (i.e., no traffic violations) for a minimum of two years from the learner’s permit stage, drivers would be eligible for a full, unrestricted licence. This aligns with a 2023 proposal by the European Commission, which suggests a probation period of at least two years for novice driver’s post-test (EC, 2023).

A 60-90 minute advanced road test would take the evaluation to a higher level, assessing a driver’s ability to handle complex and challenging driving situations. This test would build on the skills evaluated in the Intermediate test, introducing more demanding scenarios such as navigating high-traffic areas, extended highway driving, manoeuvring in adverse weather conditions and, as applicable, driving on rural and/or mountainous roads. Candidates will demonstrate advanced vehicle control, hazard perception, and the ability to remain calm and make sound decisions in stressful situations.

It is important to note that novice drivers are not considered fully accomplished or safe until they have several years and thousands of kilometres of safe independent driving experience (Simons-Morton, 2007). Driver errors decrease over time, indicating improvements in both manual skills and judgment (Ehsani et al., 2017). Research suggests that drivers generally reach a higher level of competence and safety after four years of licensed driving (VicRoads, 2019).

Ongoing driver development

To retain their driving licence, drivers with a Full Unrestricted Licence would be required to:

-

Renew their licence every 5 years (as per current law)

-

Complete a knowledge refresher course to stay updated on current traffic laws, safe driving practices, and any changes in regulations

-

Pass a theoretical exam

The proposed 5-year renewal cycle aligns with international best practices and emerging evidence on driver safety outcomes. In the USA, driver’s licences are valid in most states for 4 to 8 years, with a few states extending the validity up to 12 years (IIHS, 2024). However, in the European Union, driver’s licences are typically renewed every 10 years for Member States, with a proposal under consideration to extend the renewal period to 15 years (EU, 2023). These international practices highlight the importance of adopting periodic renewal requirements as a strategy to enhance road safety and ensure that drivers meet updated standards over time.

These renewal sessions can also serve as touchpoints for targeted campaigns addressing emerging issues or areas where legal infractions or crash statistics are rising. In some countries, a mandatory second-phase driver training program is required for novice drivers before they are granted full licensure. This training should consider cognitive and behavioural characteristics that influence young drivers’ performance such as risk-taking behaviour, hazard perception, and emotional regulation (Watson-Brown et al., 2024).

Revised curriculum

Existing driver education curricula for licence types A (motorcycles), B (private vehicles), and F (vehicles adapted for individuals with disabilities) need significant revisions to align with international best practices. The following key elements are not currently in place and should be considered for incorporation into the revised curricula:

-

Employment of Certified Driver Education Instructors (Thomas et al., 2012)

-

Greater focus on social and contextual factors affecting driving (Rodwell et al., 2018), such as the influence of peers, fatigue and alcohol

-

Emphasis on comprehensive driver training and risk awareness, with a stronger focus on advanced driving training and hazard perception

-

Integration of technology such as driving simulators to improve hands-on learning without exposing drivers to real-world risks early on

The proposed academic curricula

The proposed academic curricula are designed to address specific concerns and driving challenges identified in local crash statistics and driver behaviour studies in Ecuador. By aligning with international best practices and tailoring content to the local driving environment, this comprehensive Driver Learning System aims to significantly improve road safety and driver competence across Ecuador. Table 2 is a comparison between the current system and the proposed system for each licence type (A, B, and F).

Enforcement and penalties

To ensure compliance with the DLS system and promote safer driving behaviours, a robust enforcement and penalty structure is proposed that includes:

-

Strict enforcement of GDL restrictions: Authorities would rigorously enforce the restrictions imposed during the Learner’s Permit and Intermediate Licence stages, such as night driving and passenger limits, through regular checks and monitoring.

-

Introduction of “L” (Learner) and “P” (Provisional) plates: To easily identify drivers in the Learner’s Permit (L plates) and Intermediate Licence (P plates) stages. These identifiers would help law enforcement and other road users recognise drivers with restrictions, facilitating better enforcement of the GDL system. It will also increase awareness of a novice driver to other road users and may increase empathy from experienced drivers.

-

Higher penalties for violations during Learner’s/Intermediate stages: Violations committed during the initial stages of the GDL system would be subject to higher penalties than for full licensed drivers. Escalating penalties are likely to serve as deterrents and reinforcing the importance of adhering to the regulations.

-

Requirement of driver’s education for traffic violators: Individuals who commit traffic violations, regardless of their licence stage, may be required to attend additional driver’s education or refresher programs to regain or retain their driving privileges.

The current law in Ecuador, the Ley Orgánica de Transporte Terrestre, Tránsito y Seguridad Vial in 2021, provides a foundation for traffic regulations. This proposal suggests amendments to:

-

Strengthen enforcement mechanisms

-

Establish a clear structure for escalating penalties for GDL violations

-

Integrate the DLS requirements into the existing legal framework

Research supports this comprehensive approach. Implementing comprehensive three-stage Graduated Licensing Systems, along with stricter enforcement of safety laws and enhanced vehicle safety features, has been shown to significantly reduce crash risk among young, novice drivers (Gillan, 2006).

Challenges in implementing the DLS

Implementing the proposed DLS in Ecuador will face several significant challenges that need to be addressed through planning and resource allocation. These challenges include:

-

Resistance to change: there may be resistance from various stakeholders, including current driving schools, instructors, and even some members of the public who are accustomed to the existing system.

-

Resource allocation: implementing a robust DLS requires significant resources, including funding for training facilities, certified instructors, educational materials, and technological tools like driving simulators. Securing adequate resources may be challenging, especially in a context of competing priorities.

-

Infrastructure and accessibility: ensuring widespread accessibility to DLS training facilities and resources across different regions of Ecuador, including rural areas, may be a logistical challenge. Access to technology and internet connectivity for online educational tools could also pose barriers.

-

Educational standards and curriculum development: developing updated and standardised curricula that meet international best practices while also addressing local road safety challenges requires careful planning and collaboration with educational experts and stakeholders.

-

Teacher training and capacity building: training existing and new instructors to meet the standards required for teaching under the DLS framework may require time and investment. Ensuring that instructors are well-prepared to deliver high-quality education is essential for the program’s success.

-

Increased costs and accessibility for disadvantaged populations: the proposed DLS, which includes an increase in required supervised driving hours and the potential for higher licensing costs, could disproportionately affect economically disadvantaged families. To mitigate this, subsidies or financial support for low-income families are recommended. Additionally, mechanisms such as community-based supervision programs could be explored to ensure that all young people have equal access to licensure. Careful consideration is needed to avoid unintended consequences, such as an increase in unlicensed driving due to these barriers.

-

Enforcement and regulation: strict enforcement of DLS regulations, such as monitoring compliance with GDL restrictions and enforcing penalties for violations, requires coordination among law enforcement agencies and may face challenges related to capacity and resources.

-

Public awareness and acceptance: educating the public about the benefits of the DLS and gaining widespread acceptance and support for new regulations and educational requirements may take time and effort.

-

Political will and stakeholder engagement: garnering sustained political will and engagement from key stakeholders, including government officials, legislators, and advocacy groups, is crucial for overcoming bureaucratic hurdles and ensuring long-term commitment to the DLS.

Given the mountainous terrain and challenging road conditions in Ecuador, the DLS must incorporate specific training on handling elevation changes, adverse weather and winding roads. The use of advanced driving simulators would provide a controlled environment for drivers to practice these skills safely. Simulators offer the added benefit of immediate feedback, helping instructors tailor training to each learner’s needs.

To ensure successful implementation, a coordinated effort involving the Ministry of Transportation, the National Transit Agency (ANT), driving schools, and other stakeholders is essential. Support mechanisms, such as grants for disadvantaged families and community-based driver supervision programs, could alleviate cost-related barriers. Additionally, online learning platforms and mobile units for remote areas can help overcome geographical limitations. Engaging international experts and establishing monitoring systems will further enhance the program’s effectiveness. Continuous collaboration with policymakers will also be key to enacting supportive legislation and ensuring sustained resources for the DLS.

Conclusions

The proposed Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL) system represents a transformative step in addressing persistent road safety challenges in Ecuador. Grounded in international evidence, the GDL framework focuses on reducing high-risk behaviours among novice drivers through progressive learning stages, structured exposure to driving environments, and tailored restrictions. By integrating advanced training techniques, risk awareness, and continuous evaluation, the GDL system aligns with proven strategies to decrease crash rates and fatalities. While challenges such as stakeholder resistance and resource allocation must be addressed, the GDL system provides a robust, evidence-based foundation for reforming driver licensing in Ecuador. Its successful implementation offers the potential to significantly improve road safety and establish a model for other nations facing similar challenges.

The DLS integrates traffic safety education in schools, implements a three-stage Graduated Driver Licensing system, updates curricula across all licence categories and promotes continuous learning. It addresses specific concerns identified in local crash statistics and driver behaviour studies, aiming to significantly improve road safety and driver competence nationwide. Successful implementation of the DLS will face challenges, including potential stakeholder resistance, resource allocation issues, and the need for widespread accessibility to training facilities. Overcoming these obstacles will require coordinated efforts from government agencies, driving schools, and other stakeholders, as well as sustained political will and public support.

The potential benefits of the DLS are significant. By fostering a culture of safe driving through comprehensive education and structured learning phases, Ecuador can work towards reducing traffic crashes, injuries, and fatalities, aligning with both national road safety goals and international initiatives. While the road to improved road safety in Ecuador is challenging, the proposed system offers a promising and comprehensive approach. By investing in thorough a graduated licensing system, Ecuador can create safer roads for all users and set a model for other countries facing similar road safety challenges. Future research should focus on monitoring the DLS implementation, evaluating its effectiveness, and exploring the integration of emerging technologies to further enhance road safety outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges that ChatGPT 3.5 was used in the preparation of this paper to assist with English language expression and clarity.

Author Contributions

The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors

Human Research Ethics Review

Not applicable. No humans nor data related to humans was used in this study.

Data availability statement

The author declares that no materials, data nor protocols were used.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.