Introduction

Dangerous and reckless drivers are a threat to themselves and the community, and in most countries the public is encouraged to report evidence of such driving. In Australia, high-level speeding offences, and dangerous or careless driving involving improper use of a motor vehicle (i.e., intentional loss of traction in burnouts, drag racing and donuts on public roads), have been given a special name. They are referred to as “hoon” offences (Victoria Legal Aid, 2023). Leal and Watson (2011) reported that 3.7 percent of illegal street racing offences brought to police attention resulted in crashes, while speeding violations resulting in licence suspension, more than any other type of offence, were associated with increased injury severity in crashes (Hamzeie et al., 2017).

In Victoria, Australia, hoon offences include:

-

exceeding the speed limit by 45 km/h or more in any speed zone

-

travelling at 145 km/h or more in a 110 km/h zone

-

loss of traction in combination with careless or dangerous driving

-

causing excessive noise or smoke by improper use of a motor vehicle

-

organising or engaging in a race/speed trial

Drivers who commit a hoon offence may have their vehicle impounded immediately for up to 30 days, with an impoundment of at least three months for repeat offenders or offenders who exceed the speed limit by 70 km/h or more. In addition, there may be considerable fines and even imprisonment for repeated hoon offending (Victoria Legal Aid, 2023).

Since 20 February 2013, hoon offenders have also been ordered by court magistrates to complete a Safe Driving Program called the SDP (VicRoads, 2023). This is a behaviour change program consisting of a 5-hour facilitated group discussion among 4 to 12 participants who have all received a court order to attend the program. The broad aim of the program is to reduce the likelihood of participants engaging in unsafe driving/riding, offending and hoon public nuisance behaviours in the future. The program is designed to enable participants to develop an understanding of their motivations and triggers for high risk and anti-social driving, while also developing strategies to avoid these behaviours in the future.

The program is delivered by the Victorian Department of Transport and Planning (DTP) through approved providers, and only these providers can issue a Completion Certificate to prove that the SDP has been completed. A hoon offender has four months from the date of notification to complete the SDP, with additional licence suspensions or disqualifications imposed if this does not occur. SDP orders are mandated by the courts and additional penalties such as licence disqualification, fines and vehicle impoundment are often imposed at this time. Between May 2014 and December 2020, an average of 55 hoon drivers were ordered to complete this program each month. It is in this context that the evaluation of the SDP has been conducted, using a before/after treatment/control group longitudinal design, whilst controlling for confounding factors.

Study Aims

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether traffic offending and crashing were statistically significantly reduced after completing the SDP. Secondary aims were to explore possible reasons for the failure of offenders to complete the SDP when ordered to do so by the court magistrates, and to determine if any improvements for the SDP need to be considered.

Method

Evaluation of Large-Scale Road Safety Interventions

In many countries, including Australia, detailed official information is collected on the licensing and offence history of drivers (including motorcyclists). In these countries, it is therefore possible to conduct evaluations of intervention programs involving large sections of the driving population. This means that sample sizes can be large and there is considerable detail available on the police-reported offending behaviour of individual drivers and the penalties imposed. However, working with such observational data rather than experimental data does have drawbacks when evaluating such programs. Most importantly, drivers cannot be randomly allocated to intervention and control groups. Instead, pseudo control groups need to be artificially constructed, representing some “control intervention”, ideally with careful matching of the intervention and control groups in terms of demographic factors and offence history. However, this is not always possible and the use of control variables to adjust for these group differences is also sometimes problematic.

Ideally a longitudinal analysis is required for evaluation purposes, in which changes in offending in the period before and after the intervention are compared for the intervention and control groups. This can also raise challenges, especially when determining these before and after periods for a control group which may not experience any intervention.

Data

The Victorian DTP provided data from the Driver Licensing System (DLS) database and the Road Crash Information System (RCIS) database. Vehicle impoundment data were sourced from Victoria Police. In addition, dates were provided for SDP orders and SDP completion (if completed) for hoon offenders. Although the SDP was formally introduced on 20 February 2013, offenders with SDP orders placed before May 2014 were omitted to avoid what was a ‘settling-in’ period for the courts, during which time some SDP orders might have been incorrectly imposed or omitted (to allow time for magistrates to implement the new legislation requirements). Various changes and delays in the reporting systems meant that the study was confined to offences committed in the period from 2007 to 2020. Only drivers (including motorcyclists) who resided in Victoria throughout the study period and who had committed at least one hoon offence during this period according to police records were included in the study. Offences not included in police records have been excluded from this study.

Intervention and Control Groups

All offenders included in this study committed at least one hoon offence in the period 2007 to 2020. The intervention group (Group 1) consisted of offenders who received an SDP order between May 2014 and December 2020 and then proceeded to complete this program.

Two control groups were chosen for comparison. The first control group (Group 2) consisted of drivers/riders who received an SDP order between May 2014 and December 2020 but failed to complete the SDP. The second control group (Group 3) consisted of offenders who committed a hoon offence in the period 2007 to 2020 but did not receive a SDP order. For 54.7 percent of the Group 3 offenders, the hoon offence was committed before 20 February 2013, that is, before the SDP was established. For the remaining 45.3 percent of the Group 3 offenders, the magistrate did not impose an SDP order despite convicting the driver of a hoon offence.

Definition of Cut-Points for the Pre/Post Intervention Periods

The Cut-Points (to define pre and post intervention periods) were set at the SDP order date for all offenders in Groups 1 and 2. For Group 3, the Cut-Point was the date of their first hoon offence in the period 2007 to 2020. The times at risk before and after these Cut-Points should be regarded as exposure times to the risk of offence or crash. For all Group 3 offenders the offences corresponding with the first hoon offence were included in the before Cut-Point period.

Table 1 illustrates the pre/post intervention periods in red. It is important to note that many offenders were serving bans or impoundments during these times. However, these offenders often ignored such orders (Watson et al., 2020) and continued to drive illegally during these times, allowing for various driving scenarios as described below:

Scenario 0: Offenders who received their first Learner Permit before 2007 and were still alive at the end of 2020.

Scenario 1: Offenders who obtained a Learner Permit after January 2007, but before the Cut-Point and were alive at the end of December 2020.

Scenario 2: Offenders who obtained a Learner Permit, Probationary licence or full licence before 2007 but died before the end of December 2020.

Scenario 3: Offenders without a licence (Learner permit or Probationary licence or full licence) at the time of the Cut-Point (i.e., driving illegally) who were still alive at the end of December 2020. It was assumed that these offenders were driving without a licence for a full year prior to the Cut-Point, resulting in a Time at Risk of one year before the Cut-Point.

Outcome Measures

Although overall driving offending behaviours were considered in this study, the primary interest was hoon and other serious offending. These behaviours may ultimately result in crashes and fatalities or serious injuries (Palk et al., 2011), so the number of crashes as driver and the number of fatal or serious injuries resulting from these crashes were also considered as outcome measures. Hoon and other serious offence types result in bans and/or vehicle impoundments, also making the proportion of offenders receiving such penalties of interest as outcome measures.

Control Variables

Numerous variables are known to relate to offending and crashes (e.g. Meyer et al., 2021). Age, residence (major city/rural) and the Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) are commonly considered as control variables for comparisons of this nature. However, even more important than these variables is the “Time at Risk of Offending/Crashing”. Gender was not included as a control variable due to low representation of females, particularly in Group 1 (5.6%).

Statistical Analysis

Trends in Offending

An initial graphical analysis was conducted to track offence rates over time in the period 2007 to 2020 for all 3 groups when combined. Offence rates were calculated for each year by dividing the number of offences in any year by the number of offenders at risk of offence in that year, with fractions introduced for offenders who received a learner permit or died within the year (e.g. 0.5 for 6 months at risk).

Group Comparison for Demographic Variables

Chi-Squared tests of association and analysis of variance tests were used to compare the 3 groups in terms of gender, age, residence (major city/ rural) and IRSAD decile at the Cut-Point date.

Group Comparisons for Changes in Offending from Before to After the Cut-Point

The comparisons of the intervention group (Groups 1) and control groups (Group 2 and Group 3) were conducted to better understand the relative changes in offending and crash history from before to after the Cut-Point. These analyses were conducted using Generalised Estimating Equations (GEEs) to take into account the repeated measures nature of the data (with the same drivers observed in the periods before and after the Cut-Points). These models were appropriate due to the large sample sizes (Hutchings et al., 2003; Park & Pugh, 2018). It was assumed that the number of offences, crashes and fatal and serious injuries (FSIs) in each period followed a Negative Binomial distribution (Mohammadi et al., 2014).

To allow for the differences between the groups in terms of age, IRSAD decile and major city/rural residence at the time of the Cut-Point, these variables were added as control variables, together with the “Time at Risk of Offence/Crash” before and after the Cut-Point. Statistical significance levels of 5 percent were used for testing statistical significance, with values of Cramer’s V and η2 used to indicate the magnitude of the effects observed for categorical and continuous variables respectively. SAS version 9.4 and IBM SPSS Statistics version 28 were used for the preparation of the data files and the analyses respectively.

Comparison of Offending After SDP Imposition for Groups 1 and 2

A final Negative Binomial Regression Analysis was conducted to compare the offending of Groups 1 and 2 while controlling for the imposition of bans or impoundments after the Cut-Point as well as regional location, age, IRSAD decile and Time at Risk. This analysis considered only the time after SDP imposition.

Results

Trends in Offending

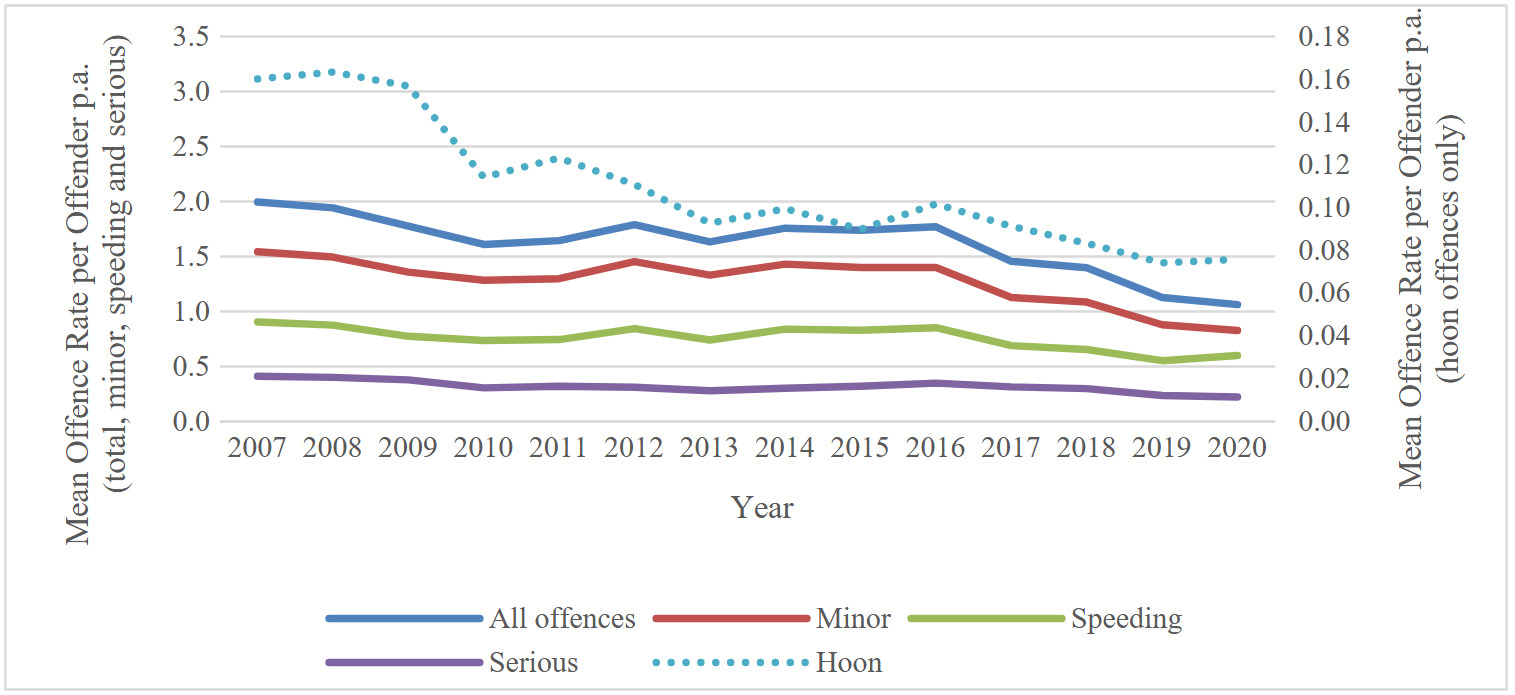

A graphical analysis was used to gain an understanding of offence rates for the offenders included in the study during the period 2007-2020 (Figure 1). Significant declines in per annum offending rates were detected for serious offending on the primary axis (p<.05). The secondary axis (right) shows a significant decline in hoon offence rate per annum with an additional significant decline from 2016, from about 0.16 offences per offender prior to 2016 to about 0.08 offences per offender after 2016. As shown on the primary axis (left), there were also additional significant declines for overall, minor and speeding offences from 2016.

Group Comparisons for Demographic Variables at the Cut-Point

The relatively large sample sizes (Group 1: n=3,324; Group 2: n=1,063; Group 3: n=30,678) meant that statistically significant differences were commonly found when the groups were compared, even when effect sizes were small. There was a statistically significant but very small difference (V=.047) in the gender breakdown for the three groups, with males more common in the SDP completion group (Group 1: 94.4%) than the control groups (Group 2: 91.6%, Group 3: 87.6%). There were again small but statistically significant age differences for the three groups (η2 = .002), with lower mean ages at the Cut-Points for Group 1 (mean=26.36 years, SD=8.27) than Group 2 (mean=28.32 years, SD=8.41) and Group 3 (mean = 27.99 years, SD=10.04). Group 2 offenders were slightly less likely to live in the major cities of Victoria (Melbourne and Geelong) than the other two groups (V=.018, Group 2: 69%, Groups 1 and 3: 74%). Finally, Group 1 offenders were less likely to live in low socio-economic decile areas (IRSAD decile < 5; V=.042, Group 1: 55%, Group 2: 61%, Group 3: 62%).

Group Comparisons for Changes in Offending from Before to After the Cut-Point

As shown in Table 2, there were marked differences in the offending patterns of Group 1 and Group 2 in the period before the imposition of SDP orders (before the Cut-Point), which needed to be considered when comparing the groups. While Group 1 offenders were more likely to have incurred vehicle impoundments (77.3% v 57.9%), the average number of offences committed per offender per annum (especially serious offences) was higher for Group 2 than Group 1 offenders, resulting in a larger proportion of bans for Group 2 offenders than Group 1 offenders (94.0% versus 85.4%). The offence rates for Group 3 were more like Group 1 prior to the Cut-Point although the rate of vehicle impoundment was much lower at only 23.7%, due perhaps to fewer court appearances. However, for all three groups Table 2 shows marked reductions in offending and penalties (bans and vehicle impoundments) after the Cut-Point.

A statistical analysis was conducted to compare changes in offending, crashes and FSIs from before to after the Cut-Point for Groups 1 and 2, with a similar comparison for Groups 1 and 3 and Groups 2 and 3. Table 3 provides the results of these GEE analyses. In all these analyses we tested for statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of the changes observed from before to after the Cut-Point, while controlling for residence (major city/rural), age and IRSAD decile at the Cut-Point, and Time at Risk of Offending/Crashing before and after the Cut-Point.

No statistically significant group differences were obtained for the number of crashes or the number of FSIs, due in part to the rarity of these events. However, for all the remaining variables, Group 1 showed statistically significant (p <.05) greater improvements than Group 3 (greater reduction for: hoon offences (18.8%); other serious offences (23.3%) and all offences (14.5%)). Group 2 also showed statistically significant greater improvements over Group 3 with greater reduction for serious offences (22.2%) and all offences (30.5%). These results indicate that the fines, bans and/or impoundments that accompanied the SDP orders have been beneficial (even without SDP completion).

The effects of SDP completion (Group 1 versus Group 2) were positive for hoon and serious offending. There were greater reductions for Group 1 in hoon (18.7%) and other serious offending (9.6%) than for Group 2, but these differences were not statistically significant. In addition, the decline in overall offending was greater for Group 2 than Group 1 and this difference was statistically significant. This can probably be explained by the very high rate of overall offending for Group 2 (75% higher than for Group 1) before the date of their SDP order.

Comparison of Offending After SDP Imposition for Groups 1 and 2

Considering only the period after SDP completion, while controlling for the imposition of bans and vehicle impoundments as well as regional location, age, IRSAD and Time at Risk, the number of serious offences was 66.9 percent lower for Group 1 than Group 2 and this difference was statistically significant. The number of careless/dangerous driving offences was also significantly lower for Group 1; however, the number of speeding offences was 56 percent higher for Group 1 than Group 2. Interestingly the percentage of drivers with unauthorised driving offences was high for both these groups, but significantly higher for Group 2 (29.1% for Group 1 drivers and 44.1% for Group 2 drivers).

Discussion

Importantly the results indicate a decline in offending after the Cut-Point for all three groups. There are several factors that may be associated with this decline. Increasing age is commonly associated with lower offence and crash rates (Meyer et al., 2021), so maturation and increased driving experience may be contributory factors. Another contributory factor may be the effects of the penalties resulting from the hoon offence associated with the Cut-Point for each offender. However, of more interest for this study are the differences observed between the three groups that can be used to measure the effects of the SDP.

Impacts of the SDP

The results suggest that the SDP has shown some success in reducing serious offending. However, no statistically significant differences in crash and FSI rates were observed, probably due to the relatively small numbers of these events.

Comparison of hoon offenders who received an SDP order (Groups 1 and 2) with those that did not (Group 3) shows evidence of reduced offending overall. This may be partly due to the vehicle impoundment penalties that are more regularly ordered by a magistrate when an SDP is imposed. Vehicle impoundment in Victoria has been previously found to act as an important deterrent to reoffending in Victorian high-level/serious speeding drivers (Watson et al., 2020), so it is perhaps not surprising that reductions in offending appear to be greater for offenders who receive SDP orders. Notably, approximately 40 percent (n=12,300) of the Group 3 drivers committed a hoon offence when the SDP was fully operational (after the ‘settling in’ period" was completed on 1 May 2014). This is a concern and suggests that magistrates need to be reminded of their legislated obligation to impose SDP orders on hoon drivers.

The results suggest that for those drivers ordered to complete the SDP, completing the program (Group 1) was associated with a greater reductions in impoundments, hoon and serious offending compared to those not completing the program (Group 2). Although these effects were not significant, it was found that the rate of serious offending was significantly lower for Group 1 than Group 2 in the period after the SDP imposition. This suggests that there are advantages for SDP completion, indicating that the reasons for failure to complete the SDP, despite the resulting penalties, need to be further investigated.

Group 2 offenders differed from Group 1 offenders in several respects. They were more likely to live in regional areas, perhaps making access to the SDP more difficult. In addition, they tended to live in lower socio-economic areas, perhaps making the cost of the SDP (approximately $800) more of a barrier. Ways to address barriers to SDP completion for these offenders while also reducing SDP costs could be explored. A third difference relates to the more serious and more frequent offending of Group 2 offenders prior to their SDP order. This would have resulted in higher fines and longer bans and impoundments, perhaps explaining the delay in SDP completion for Group 2. This suggests that issues associated with delay in SDP completion could be investigated, regardless of the length of any outstanding bans, with more immediate follow-up by authorities when SDP completion does not occur within the legislated four-month period. One of the determinants of the road safety effectiveness of targeted deterrence sanctions is the swiftness with which these sanctions are applied (Davey & Freeman, 2011).

There is a proportion of drivers (17.2%) who continue to commit serious offences that result in vehicle impoundments even after completion of the SDP. Currently there is no repeat SDP for such offenders and a compulsory refresher course or follow-up messaging of some form could perhaps be considered for these recidivist serious offenders. The installation of telematics devices is another option for these drivers. Telematics is a relatively new technology, which involves the transmission of driving behaviour information (e.g., acceleration, braking and speed measures) over long distances. This information could be used to trigger alerts to warn offenders and authorities when unsafe behaviours are evident (Boylan et al., 2024; Kirushanth & Kabaso, 2018).

Another finding from this study has been the number of drivers with unauthorised driving offences. The average number of such offences per offender was high for all the groups during the period 2007-2019 (Group 1: 2.1; Group 2: 6.1; Group 3: 2.4). This suggests that the penalties for these offences are not creating a deterrent effect, which may be due to offenders having other social determinants (i.e., life problems) that reduce the perceived impact or importance of unauthorised driving consequences. As indicated in Table 2, bans are more likely to be imposed on hoon drivers than vehicle impoundments. It may be that vehicle impoundments would be a more successful method for reducing unauthorised driving, although it is noted that offenders can gain access to a non-impounded vehicle.

Study strengths and limitations

The design used for this study endeavoured to address the problems identified in previous evaluation studies of this nature. The use of official offence, crash and impoundment data resulted in large samples of detailed, largely accurate data. As shown in Figure 1, there was a very marked decline in the offending of these drivers over the period 2007 and 2020, perhaps related to the increasing maturation and experience of drivers, as well as the introduction of 48-hour impoundments in July 2006, increased to 30-day impoundments in July 2011. This decline makes a longitudinal analysis with control groups appropriate for the testing of the impact of the SDP.

It is acknowledged that the control groups were not ideal as the allocation into intervention and control groups was not random, resulting in some important group differences at the Cut-Point, despite our best efforts to produce meaningful control groups. However, in the ensuing statistical analysis, there was a judicious use of control variables to account for these group differences, and appropriate statistical methodologies that accounted for the data distributions.

Group 2 consisted of offenders who were given an SDP order but did not complete the program. Group 2 had higher rates of offending prior to their SDP order than Group 1. This meant that the decline in the rate of overall offending observed for Group 2 exceeded that for Group 1. The very high rates of offending for Group 2 before their SDP orders may well relate to their failure to complete their SDP (e.g., these offenders may have had a higher risk-taking propensity or other social determinants that contributed to their offending and lack of compliance), and further research is needed to understand if this is the case.

Group 3 consisted of offenders who were not ordered to complete the SDP despite having committed at least one hoon offence in the period 2007-2020. The majority of these offenders committed their first hoon offence before the SDP came into operation, but a large percentage (approximately 40% after the SDP was fully operational) had never received an SDP order despite legislation requiring the order. The reasons for this could be further investigated. It is acknowledged that the Cut-Point for Group 3 was chosen as the date of the first hoon offence, which would have preceded the date of conviction for this offence, while the Cut-Point for Groups 1 and 2 was chosen as their SDP order date following conviction for a hoon offence. The impact of these choices on the results could also be investigated.

Another limitation was the inclusion of the hoon offence for the period before the Cut-Point. This hoon offence was instrumental for the choice of study participants, but, strictly speaking, it would have been better to remove this single offence for the longitudinal study to avoid regression to the mean. However, the relatively high rates for other offence types in the before Cut-Point period suggest that this would have had little impact on the final results.

The Time at Risk was not reduced to account for the duration of bans and vehicle impoundments despite previous work showing that offending rates decrease significantly during bans (Imberger et al., 2019). However, the high numbers for unauthorised driving offences suggest that for this cohort of drivers the likelihood of driving despite bans and impoundments is relatively high. The final limitation of this study is the relative rarity of crashes which meant that the effects of the SDP on crashes involving hoon drivers, and the resulting FSIs, could not be reliably assessed.

Future research

While findings from this study evaluated the SDP, they also raised new questions that would benefit further study.

An area for future research is the reasons for serious reoffence(s) resulting in vehicle impoundments for offenders after receipt of an SDP order (Group 1: 17.2%; Group 2: 21.5%). These reasons are not well understood and need to be examined to determine if anything more, apart from individual case management, can be done to stop this serious reoffending and its potential for causing harm on Victorian roads (Baltruschat et al., 2021).

Offenders who committed hoon offences before receiving a learner permit are another group of concern (n=1,997). For the purposes of this study, it was assumed that these drivers drove illegally for a year prior to the Cut-Point (SDP order for Groups 1 and 2, first hoon offence for Group 3). Further investigation is needed to test this assumption and determine if/how motivations contributed to these driver behaviours and if suitable interventions may have helped prevent their illegal or hoon driving behaviours (e.g. Pressley et al., 2016).

Conclusions

The overall decline in hoon offending observed since 2007 indicates that hoon offending was being successfully addressed even before the SDP was introduced. However, the comparisons of offenders who completed the SDP compared with those who did not, indicate that SDP orders and the associated driving bans and vehicle impoundments have further reduced hoon and other offences, even when the SDP is not completed. However, the comparison of Groups 1 and 2 indicates that the completion of the SDP has particular advantages in terms of serious offending, making it important that efforts to ensure SDP completion are prioritised. Nevertheless, a small number of repeat offenders remain, and for these offenders repeat SDPs and other measures are worthy of consideration, including exploration of ways to encourage rapid SDP completion and ways to overcome barriers to SDP completion, including cost. The extension of the SDP to include case management intervention for recidivist offenders could also be considered.

Acknowledgements

Swinburne University would like to thank the Victorian Department of Transport and Planning for funding this study and the co-authors for their data provision and preparation, research and policy project inputs, as well as inputs into this journal paper. The Victorian Department of Transport and Planning provided critical information in relation to the SDP program evaluated in this study, also organising access to all the de-identified data.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation (DM, KI, JC, CE); Data Curation (DM, KI, WSC, JC); Methodology (DM, KI); Formal Analysis (DM); Funding Acquisition (KI, DM); Project Administration (DM, KI); Writing, original draft (DM); Writing, Review and Editing (DM, KI, WSC, CE, JC, RS, JB).

Funding

This work was supported by the Victorian Department of Transport and Planning, Australia (DTPRJ21904).

Human Research Ethics Review

The study was conducted using the study protocols reviewed and approved by the Swinburne University Human Research Ethics Committee (SUHREC 2022/6551). The Victoria Police Research Coordinating Committee provided approval for the use of the impoundment data (RCC 1039).

Data availability statement

Requests for data associated with this publication should be addressed to the Victorian Department of Transport and Planning, Australia.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.