Introduction

A “traffic incident” is defined as any non-recurring event that causes a reduction of roadway capacity or an abnormal increase in demand including but not limited to traffic crashes, disabled vehicles, spilled cargo, highway maintenance, reconstruction projects, and non-emergency events (Farradyne, 2000). “Traffic incident response” is the activation of a strategy for the safe and rapid deployment of the appropriate personnel and resources to the incident scene for traffic incident management (Emergency Responder Safety Institute, 2009; Federal Highway Administration, 2010). Effective traffic incident management may help relieve congestion, improve operational efficiency, reduce traffic emissions, and decrease the risk for secondary incidents, rates of injuries, and mortalities caused by secondary incidents – incidents that occur after the initial incident as a result of the changed conditions caused by the initial incident, such as unexpected slowed or stopped traffic (Cattermole-Terzic & Horberry, 2020; Emergency Responder Safety Institute, 2009). During traffic incidents, teams of public safety and transportation professionals may arrive at the scene of an incident to offer assistance. Traffic incident response professionals include agencies such as law enforcement, fire and rescue services, emergency medical services (EMS), the department of transportation (DOT), public safety communications, towing and recovery services, hazardous materials contractors, and traffic information media.

Although the most common problem associated with traffic incidents is traveller delay, a more serious problem is the risk of secondary crashes and the danger posed to response personnel at the scene. Professionals responding to roadway crashes are often significantly at risk for injuries and fatalities while working on the side of the roads due to incident-caused congestion and traffic system disruptions. In the United States of America (U.S.) in 2023 alone, there were 45 fatalities reported among traffic incident response personnel due to “struck-by-vehicle” incidents (Emergency Responder Safety Institute, 2023). Of the 45 people killed, 18 were law enforcement, 20 were tow truck operators, and 8 were from fire/EMS. It is likely that one of the major causes of secondary crashes involving incident response personnel is motorists not moving over when approaching the incident scene.

In response to an increasing number of occupation related fatalities among first responders at incident sites, all states have adopted move-over laws that serve to ensure a buffer area between moving traffic and traffic incident response personnel. Such laws vary by state and typically require motorists approaching one or more emergency vehicles parked in the shoulder of a road to slow down or move-over to adjacent lanes (Birenbaum et al., 2009). Despite their importance, however, much of the American population is not aware that move-over laws exist (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, n.d.).

Carrick and Washburn (2012) examined motorists’ compliance with move-over laws in Florida by staging police cars on the side of the road and recording the passing vehicles and measuring vehicle speeds. During the study period, around 75 percent of observed vehicles complied with Florida’s move-over law. The compliance increased to 80 percent when police used blue and red emergency lights in the vicinity of the incident, whereas the compliance was only 68 percent when amber lights were used. This finding was consistent with Megat-Johari et al. (2021) who found that drivers were more likely to decrease their speeds or move over if a police car was located on the shoulder of the road as compared to a transportation agency vehicle. Additionally, Megat-Johari et al. (2021) found that traffic volume, and the share of heavy vehicles in the traffic flow had a significant effect on driver compliance with move-over laws. Carrick and Washburn (2012) point out that the lack of driver knowledge of the requirements of move-over laws was one of the primary reasons for non-compliance.

Muir et al. (2020) examined slow-down and move-over laws in Australia and reported that most Australian jurisdictions had the same rule in place with regard to the speed limit of 40 km/h applied when passing an emergency vehicle, except for South Australia (where the limit of 25 km/h limit was used) and New South Wales (where the limit of 40km/h only applied to roads with a posted speed limit of 80 km/h or below). However, other parameters related to the rule (such as vehicle categories covered under the rule, associated penalties, etc.) varied among states. While the experience of Australian jurisdictions was not systematically analysed or articulated, the study reports that most jurisdictions were satisfied with the way their rule was performing (Muir et al., 2020).

The lack of research examining the effectiveness of, and levels of compliance with, move-over laws in the U.S. and internationally is striking. To the authors’ knowledge, Carrick and Washburn’s (2012), Muir et al. (2020) and Megat-Johari et al. (2021) are among very few studies published on the topic.

The goal of this study is to provide an overview of move-over laws by U.S. states, identify gaps in such laws and regulations and propose recommendations that offer better protection to incident response personnel when they are actively working on the roads. By highlighting the areas for improvement, this study will be beneficial to policymakers, road safety advocates, and the general public.

Method

This paper provides an overview, as of July 2024, of existing state laws pertaining to incident response personnel safety standards for all fifty U.S. states. The overview of state laws analyses the following elements:

-

the types of incident response personnel covered;

-

speed reduction requirements;

-

monetary penalties for move-over law violations without injuries;

-

monetary penalties for move-over law violations resulting in injuries;

-

classification of the move-over law violation as a criminal or civil offence.

Nexis Uni, a legal database, was used in this study to find information about incident response personnel laws. Nexis Uni provides access to extensive legal sources for U.S. federal and state cases and statutes. The database contains a variety of legal materials including cases, statutes, law journals, and other legal resources. Nexis Uni access is provided through academic institutions but there is a similar database (Lexis) that is used by law firms and other legal professionals. The database is only available to those with a paid subscription. Once the database was accessed, each U.S. state’s statute, the primary and original source for the state’s move-over requirements, was accessed and analysed.

Results

The analysis has shown that different aspects of state move-over laws vary widely from one state to another when it comes to speed reduction requirements, offence classification types, as well as the forms and the amounts of penalties resulting from state move-over law violations. Moreover, it was found that not all states include move-over laws pertaining to all themes mentioned above. Key findings for each of the five move-over law themes covered in this study are summarised in the following sections.

Incident response personnel

All U.S. states have some form of move-over law, but not all incident responders are protected equally. To identify what categories of incident responders are protected under state law, state move-over statutes were reviewed for the following categories of incident responders: fire, law enforcement, paramedics, tow trucks, DOT, and other services. The review showed that every state covers at least the following three categories of emergency responders: paramedics, fire, and law enforcement officers. Tow truck drivers, DOT personnel, and other responders were not offered the same protection as other emergency response personnel (i.e., fire, paramedics and law enforcement) in all 50 states.

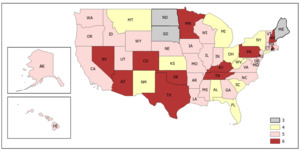

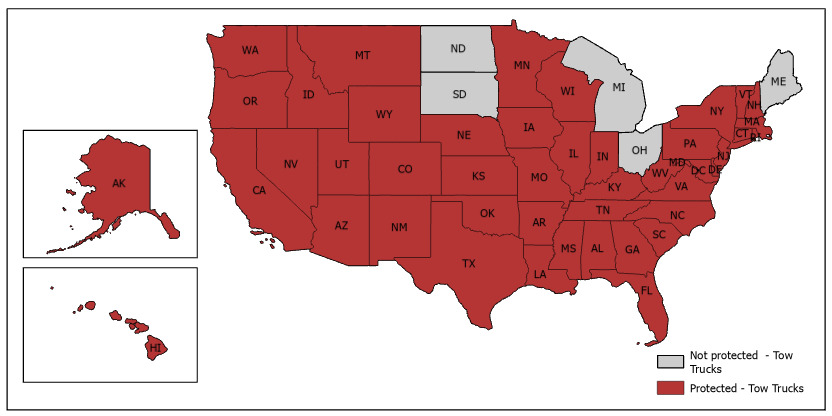

Although the majority of states protect responders travelling in tow trucks (Figure 1) and DOT vehicles (Figure 2), in most cases, state legislation does not offer the same protection to responders in other service vehicles (Figure 3). All states except Maine, Michigan, North Dakota, Ohio and South Dakota require drivers to move-over or slow down when a tow truck is parked on the highway shoulder. All states except Alabama, Connecticut, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Montana, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, South Carolina, South Dakota and West Virginia require drivers to move-over or slow down when a DOT vehicle is parked on the highway shoulder. However, fourteen states (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia) cover all service vehicles under their move-over laws and require drivers to move-over or slow down when any service vehicle is parked on the highway shoulder.

Most U.S. state statutes expressly list which vehicle and responder categories are protected under law, meaning that vehicle or responder categories not expressly listed are not covered. However, some states offer much broader protection. For example, Arizona law protects any stationary motor vehicle. In addition, Nevada law covers any motor vehicle, person, condition or other traffic hazard that is located on or near a roadway and which poses a danger to the flow of traffic. Other states do not cover a vehicle or responder category, but rather an entire scene. For instance, New Hampshire covers any incident involving a fire, collision, disaster, utility construction or maintenance, or other emergency resulting in partial or complete blockage of a highway. Furthermore, Pennsylvania protects an emergency response area or disabled vehicle. Montana covers scenes in which there is a temporary sign advising of an emergency scene or accident ahead.

States were given scores for the number of incident response personnel types that are protected at the incident site (Figure 4). For example, a score of “3” indicates protection for only three types of response personnel. Thus, a higher score denotes higher state standards for safety. In states including Arizona, Nevada, New Hampshire and Pennsylvania, legislation is framed to protect all six incident response personnel types (police, fire, EMS, tow truck, DOT, and other service). Maine, North Dakota and South Dakota offered the least protection, covering only three groups of responders.

Speed Reduction

Every state but New York has a slowdown requirement on approach to some type of incident response personnel. Under New York law, a driver is only expressly required to move over upon approaching a protected class of stationary vehicle. In all other states, a driver must slow down, but the actual speed reductions vary across states. Some states do not have a precise speed reduction requirement, for example, California, which requires a driver to slow to a reasonable speed that is safe for conditions. Some states are even less precise than California. For example, Delaware merely requires drivers to slow to a safe speed.

Other states do have precise speed reduction requirements. For example, in Alabama, if the speed limit is 25 miles per hour (mph) (40 km/h) or greater, a driver must slow to a speed that is 15 mph (24 km/h) less than the posted speed limit and if the posted speed limit is 20 mph (32 km/h) or less, a driver must slow to a speed of 10 mph (16 km/h). In addition, Florida law requires a driver to slow to a speed that is 20 mph (32 km/h) less than the posted speed limit if the speed limit is at least 25 mph (40 km/h), and if the speed limit is 20 mph (32 km/h) or less, a driver must slow to a speed of 5 mph (8 km/h).

These differences in speed requirements can lead to confusion among motorists. For example, a driver that is travelling on a road with a speed limit of 50 mph (80 km/h) from Alabama to Florida will be required to slow down to a speed of 35 mph (56 km/h) on approach to an emergency response vehicle on the shoulder of the road. But when the same driver on another section of the same road crosses the state line into Florida, they will then be required to reduce their speed to 30 mph (48 km/h). Even if a driver is aware of the speed reduction requirement, many drivers will not be aware of the specific nuances in those requirements when travelling across state lines.

Monetary Penalties without Injury

U.S. states vary considerably in the way monetary penalties are imposed on move-over law violators. Most fines are under US $500 for an initial violation, but the specificity of statutory penalties varies. For instance, California sets a maximum fine of $50, while South Dakota enforces a minimum of $270. Some states require precisely fixed amounts. Connecticut fines offenders $181 and Vermont, $335. A significant number of states, including Alabama and Arizona, increase fines for each successive violation of the move-over statute.

In some jurisdictions, the amount of the fine can as much as quadruple on the occurrence of a third offence. A few states provide a range of fines, in such cases, judicial discretion was used to potentially assess the severity of the offence and exact an appropriate amount. Wisconsin restricts the range from $30 to $300, while Illinois allows for penalties between $250 and $10,000. Oregon increases its penalty from $265 to $525 if the offence occurs within a safety corridor, school zone, or work zone. Other states have fines that vary based on the type of responder. For example, Georgia can fine drivers up to $500 when a move-over violation involves an authorised emergency vehicle, but Georgia can only fine drivers up to $250 if the violation involves only a tow truck.

It is worth remembering that these fines are explicitly for violations of the move-over law, exclusive of other penalties imposed for speeding, reckless driving, or damage to person or property.

Monetary Penalties with Injury

A few states increase the amount of monetary fines based on whether damage to property or persons occurred as a result of the move-over violation. Colorado increases its fine range from between $150 and $300 to between $300 and $1,000, in addition to increased criminal punishments. Connecticut raises its set fee of $181 to a maximum fine of $2,500 in the event of injury and $10,000 in the event of death. Illinois incorporates a criminal charge in the event of property or personnel damage in addition to high fine caps. Other states, like Iowa, set the penalty for bodily injury at $500 and death at $1,000, with additional suspended licence consequences. Michigan sets its fine based on what type of incident responder is injured during the violation. If a fireman, policeman, or ambulance responder is injured, the penalty is capped at $7,500, while the fine for any other person’s injury is capped at $1,000.

The states that set fine amounts based on responder classification always offer increased protection (i.e., increased penalties for violations of the law) for police, firefighters, and ambulance responders. The exclusion of tow truck operators, DOT personnel, and other service providers from these laws may signal that it is not as important for motorists to move-over or slow down when only those responders are on the scene, thus leading to less protection of this class of incident response personnel.

Criminal vs Civil Offence

While there will be the option for criminal penalties when a driver collides with an incident response personnel, some states have taken the further step of placing criminal offences explicitly within their move-over laws. Twenty one states have added criminal penalties for violations of their move-over laws or for a crash that caused damage or injury to a protected vehicle or responder (Figure 5). For example, Colorado law creates a misdemeanour for crashes that cause bodily injury to a protected responder and a felony for crashes that cause the death of a protected responder. However, in Alaska, any violation of its move-over law results in a misdemeanour charge with the possibility of up to one year of imprisonment. Furthermore, some states have even created a specific category of criminal offences, like Montana, which enforces an offence titled “reckless endangerment of emergency personnel.”

Finally, similar to how some states have differing fine amounts for different responder classifications, only Indiana creates a criminal offence for violations related to certain types of responders. Specifically, it is a felony in Indiana if a driver violates the move-over law and causes bodily injury to a person “affiliated with an authorised emergency vehicle.” However, other types of responders, like tow truck drivers, do not get this expanded protection.

Discussion

While all 50 U.S. states have taken steps to protect incident response personnel by implementing move-over laws, the protection these statutes offer varies significantly. The nuances and the variation in move-over laws may make it difficult for drivers to understand what the law requires of them, especially in the case of long-distance travel across multiple states. To exacerbate the issue, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reported that 70 percent of Americans are not aware that move-over laws exist (NHTSA, n.d.). Therefore, the first countermeasure to adopt to reduce incident response personnel injuries and fatalities is to educate the general public about move-over laws. NHTSA is supporting states by providing materials for public education and financially supporting awareness and enforcement activities. However, states have acknowledged that variation in statutes makes it difficult to educate the public (United States Government Accountability Office, 2020).

Some of the variation in state laws relates to which responders are protected under a move-over law. A driver from a state that does not require vehicles to move-over when there is only a tow truck on the shoulder of a road may not realise that they would be violating the move-over law in another state that does protect tow truck operators. To reduce the complication and ensure the highest level of protection for responders, states can adopt broader statutes that require drivers to move-over for all stalled vehicles or vehicles that have flashing lights (any colour).

Besides education and awareness campaigns, enforcement can drastically help increase compliance with move-over laws (Carrick & Washburn, 2012; Megat-Johari et al., 2021). No publicly available database exists to study citations issued across states for move-over law violations. Targeted enforcement combined with public awareness campaigns can yield maximum benefits compared to adopting one countermeasure alone (Megat-Johari et al., 2021).

In addition to enforcement, an efficient fine system may help promote compliance with move-over laws. Research conducted in the U.S. and Europe has shown that the financial penalty range and structure of fine and/or reward system may have a significant effect on a driver’s behaviour on the road (Elias, 2018; Hössinger & Berger, 2012; Reed, 2001) States that levy lower penalties for move-over law violations may risk downplaying the significance to the public in moving over when responders are at an incident site while higher fine may better incentivise drivers than a lesser fine. Furthermore, states should modify their statutes in such a way as to eliminate differentiation among responders and provide the highest level of protection to all groups.

Additionally, since the effectiveness of move-over laws depends on driver cooperation (Carson, 2008), such laws need to be clear and easy to understand for the general public. While in some states, move-over laws include explicit provisions for drivers and are easier to understand, follow, and enforce, in other states, move-over laws may be overly detailed and may therefore be more challenging to understand, comply with, and enforce. For example, California requires drivers to move over if it is “safe or practicable” and requires drivers to slow down to a “reasonable and prudent speed” if it would be “unsafe or impracticable to move over”. Alternatively, Florida requires drivers to move over when travelling in the same direction as an emergency vehicle on a “highway with two or more lanes” and requires drivers to slow down to “20 mph (32 km/h) less than posted speed limit if the posted speed limit is 25 mph (40km/h) or greater; or travel at 5 mph (8km/h) when the posted speed limit is 20 mph (32 km/h) or less” if moving over “cannot be safely accomplished”.

States recommend varying degrees of speed reductions in case moving over is not safe for the driver. For example, as stated above, in Alabama if the speed limit is 25 mph (40 km/h) or greater, a driver must slow to a speed that is 15 mph (24 km/h) less than the posted speed limit and if the posted speed limit is 20 mph (32 km/h) or less, a driver must slow to a speed of 10 mph (16 km/h). It would be difficult for drivers to remember these numbers and make calculations when approaching an incident site. Further, if a motorist in Alabama driving on an interstate with a 70 mph (112 km/h) posted speed limit approaches an emergency vehicle, they can either move-over or drive at a maximum speed of 60 mph (75-15 mph) (96 km/h; 120-24 km/h) to comply with the current Alabama move-over statue. However, if the motorist hits a responder at 60 mph (96 km/h), the chance of the responder surviving is very small.

According to a study by Tefft (2013) on pedestrian injury severity as a result of a crash with a motor vehicle, the average risk reaches 10 percent at an impact speed of 17 mph (27 km/h), 25 percent at 24.9 mph (40 km/h), 50 percent at 33 mph (53 km/h), 75 percent at 40.8 mph (65 km/h), and 90 percent at 48.1 mph (77 km/h). The average risk of death for a pedestrian reaches 10 percent at an impact speed of 23 mph (37 km/h), 25 percent at 32 mph (51 km/h), 50 percent at 42 mph (67 km/h), 75 percent at 50 mph (80 km/h), and 90 percent at 58 mph (93 km/h). Therefore, rather than recommending a nominal reduction in speeds, states should adopt speed reductions that could help increase the chance of survival and reduce the chance of injuries to the responders.

A potential model for this legislation is Australia’s move-over law where drivers passing a stopped emergency service vehicle are required to slow down to a maximum speed of 40 km/h (25mph) (Muir et al., 2020). This single maximum speed requirement applies to majority of states, regardless of the type of road or posted speed limit (Muir et al., 2020). This one-speed, blanket approach simplifies the legal requirements drivers must commit to memory. It also greatly reduces the likelihood of a fatality for roadside workers, because the slowdown speed is not relative to the posted speed limit. However, it is worth noting that we did not find a study evaluating the safety of this type of slowdown mandate for drivers travelling at high speeds. Evaluating international examples enhances our understanding of methods for consolidating and simplifying move-over regulations.

Although the primary objective of state move-over laws is to ensure the safety of incident response personnel, their effective implementation can also help reduce the frequency and severity of secondary crashes, expedite incident clearance, and reduce congestion, thus increasing road safety for all users. Conversely, variations among state laws and lack of protection for some responders could cause a higher frequency of secondary crashes and create a higher level of risk to incident response personnel.

Conclusions

This study has found that there is a great variation when it comes to state laws in the U.S. pertaining to incident response personnel safety. Particularly, state safety standards vary widely with regard to the types of incident responders protected under the move-over laws, speed reduction requirements, offence type classification, the forms and the amounts of penalties for move-over law violations. NHTSA has already identified that the majority of Americans are unaware of the existence of move-over laws. Through move-over laws, states have defined a very specific set of actions for drivers to perform when they encounter emergency vehicles on the side of the road. The variation in these requirements across U.S. states makes it highly difficult to educate the public. Moreover, the fact that not all states include laws pertaining to all themes makes it difficult to make comparisons on these themes for all states.

Every state covers at least the following three categories of emergency responders: paramedics, fire, and law enforcement people. The protection of other incident responder categories, such as tow truck drivers and DOT vehicles, varies on a state-by-state basis. This study found that in Arizona, Nevada, New Hampshire and Pennsylvania, legislation is framed to protect all six incident response personnel types (police, fire, EMS, tow truck, DOT, and other service responders) while Maine, North Dakota and South Dakota offer the least protection, covering only three groups of responders.

The overview of state incident response personnel laws provided in this paper could be helpful to safety researchers, stakeholders and policymakers. The wide variation in state laws pertaining to incident response personnel safety shows the need for revision in the statutes to offer greater protection to its responders. Additionally, due to the relative novelty of move-over laws, the wide variation of these laws from one state to another, and the current lack of research on the topic, it may be challenging to understand which move-over laws model among states is “best practice”. Therefore, further research is be needed to better understand the effectiveness of the different aspects of move-over laws (e.g., speed reduction requirement, amount of monetary penalties, etc.), on the safety of incident response personnel and other road users.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: Praveena Penmentsa, Olga Bredikhina, Justin Fisher, Sanaa Rafique. Data collection: Trayce Hockstad, Justin Fisher. Analysis and interpretation of results: Justin Fisher, Trayce Hockstad, Praveena Penmetsa, Olga Bredikhina. Draft manuscript preparation: Olga Bredikhina, Trayce Hockstad, Justin Fisher, Praveena Penmetsa. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

The authors declare that no materials, data nor protocols were used.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.