Introduction

Road safety is a major global problem, with more than 1 million people killed each year (WHO, 2023) and tens of millions injured (WHO, 2018). It is also a major equity issue, as about 92 percent of road traffic fatalities occur in low- and middle-income countries (WHO, 2023). When road safety began to be acknowledged as a significant issue in high income countries, the dominant narrative was to assume that individuals (usually vehicle operators) were responsible for crashes (Hughes et al., 2015).

In recent years, a systems orientation has become more widely adopted, in particular the “safe system approach” (Mooren & Shuey, 2024). Rather than focusing on the failures of individuals, it emphasises the responsibility of system managers to ensure that roads and vehicles are built to eliminate or mitigate injuries in a traffic crash. Road users are considered to have a shared responsibility, while their vulnerability to injury and susceptibility to mistakes are acknowledged. Although the safe system approach appears to shift responsibility to system managers rather than system users, recent analysis and research by Chirles et al. (2024) concluded that coordination and partnerships between system managers and the community is necessary for safe system success.

Coordination between road safety system managers (e.g., transport departments and police agencies) has a long history, however, coordination with the community is typically less structured and inconsistent (Green et al., 2023). The research reported below is an attempt to articulate and share learnings about coordination between government and community to improve road safety. An additional aim is to facilitate the recommended transfer of knowledge about effective coordination from high income countries that have been successful in reducing their road trauma, in the hope that their experiences can inform approaches to road safety in low- and middle-income countries.

Clarification of coordination as a concept: Background

As a starting point, a working definition of “coordination” that can be applied to road safety is needed, along with some specific examples of its application. The term coordination is interchangeably used with such ubiquitous concepts as inter-organisational systems (Khademi & Choupani, 2018) and road safety partnerships (Norman et al., 2015). In the sense used in this paper, it is not to be confused with a much broader term, namely: “whole of government” (Christensen & Lægreid, 2007). The latter term tends to mean the interaction between government agencies or programs, which is not dissimilar to its conception in early studies (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1968; Ven et al., 1976). The sense used in this paper is that applied in Fink (2011), that is, the process through which government agencies interact with community groups to co-develop road traffic trauma prevention activities. This paper will, henceforth, use the term government-community road traffic trauma prevention coordination (G-C RTTP coordination) to refer to its key object of study.

While coordination has not been specifically defined in the road safety literature, the nature of its interaction across programs has been more broadly clarified in the Health sector. It is said to represent ‘… a search to connect the health care system … with other human service systems … in order to improve outcomes …’ (Leutz, 1999, pp. 77–8). This outcome-oriented search to connect has been achieved in the United Kingdom (UK) through the Community Care Act 1990, which directed health and local authorities to cooperate in planning and purchasing services (Leutz, 1999).

Coordination also represents the linkage across programs and agendas (Camkin, 2010) of governments and communities. These connections are thought to have the potential to strengthen road safety interventions (Camkin, 2010). In addition to representing connections, coordination is also believed to harmonise road safety activities by building institutional capability (Bliss & Breen, 2009).

Service-oriented cooperation can take the form of reorganised public systems, as is the case in the UK (e.g., health system) or the adoption of models, as it is the case in the United States of America (U.S.) (e.g., public care models) (Leutz, 1999). In Australia, where local councils are responsible for 80 per cent of all roads (Lake, 2010), partnership agreements and steering committees are often adopted to secure the connection across services (Lake, 2010). These steering committees comprise representatives from the relevant local council, local government association, the department of transport, police services, health services, engineering institutes and main roads officials (Lake, 2010).

In the Netherlands, the coordinating mechanisms go beyond agreements and steering committees, and is inherently and intrinsically associated with the way the government functions. For example, a three-tier governance structure is used in the Netherlands with the central government at the top (OECD, 2006). In this governance structure, the central government exerts strong influence on local policy through national policy frameworks, which guide action at the local level (OECD, 2006). The second tier (provincial authorities) coordinates the implementation of road safety interventions (OECD, 2006). The bottom tier (municipal) executes the actual tasks emerging out of the national policy framework (OECD, 2006). This lower tier is seen to possess ‘general competence’ (OECD, 2006). However, this low governance level is not expected to be constrained by the policies set down by the central government (OECD, 2006).

Other intervention coordination implementation mechanisms in the Netherlands have included mutual administrative contracts, which are entered into by all the tiers of the hierarchy (OECD, 2006). In addition, the Framework Act, enacted in 1993, formalised cooperation. In this context, other agreements are signed. For instance, the VERDI Accords, which constitute a principle of coordinated activity across the tiers of governance (OECD, 2006) are examples of the numerous agreements entered into by the relevant stakeholders. Moreover, the policy framework, comprising integrated transport plans such as the National Traffic and Transport Plan, enhances responsibility for urban transport at a local level (OECD, 2006).

Since the Netherlands example is to some degree context-bound, and there are limitations to the applicability of health models of coordination, a structured review of the literature was undertaken. The inclusion criteria comprised the following screening items: a) recent studies (last 10 years); b) coordination as the chief object of study (in the title); c) in road safety or road traffic injury prevention contexts; d) if not in road safety, in a closely related field such as health care services because road safety is a public health issue; e) academic investigations of scholarly repute rather than opinion pieces or official reports; and f) in an OECD context as the potential site of best practices in road traffic trauma reduction.

To operationalise these inclusion criteria, the following search terms were used: TitleCombined:(coordination)) AND (“road safety”); “content analysis” AND coordination; and (TitleCombined:(coordination)) AND (“road safety”) AND (community) AND (government). The Boolean operator (AND) allowed qualitative analyses to be filtered into the review. These search terms were used across a wide range of databases catalogued by the Queensland University of Technology library.

As the retrieved studies were reviewed through an examination of the abstracts initially, the inclusion criteria were applied. This exercise excluded studies about coordination in software development, school contexts, individual units, human developmental coordination and traffic signal coordination.

Coordination review outcomes and introduction to workflows

When additional filtering was applied (year, scholarly publications and journal articles), the search exercise yielded no studies that appeared to have investigated coordination as a separate process for road safety and road trauma reduction.

Various non-road safety studies met the fourth criterion (i.e. d.). Because of the numerous examinations in the healthcare sector of the care coordination process, additional criteria were employed to narrow the studies down to a few representative ones. This selection aid entailed examining the contents of the articles for the following attributes: clarity in the identification of the type of coordination; methodical description of the data analysis including a synthesis approach; some mention of a model of coordination; and identification of critical success factors for enhanced coordination. Of particular interest was the potential for the studies to shed light on the interaction between government staff and civil society agents.

This was a departure from established work in coordination. Early studies of coordination (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1968; Ven et al., 1976) focused primarily on organisational units of work. These units of work represented workers in the same institution who operated in different departments (units or divisions) coordinating a part of their work functions, with the overall process of work (sequence and responsibilities) being the workflow. The studies in Table 1 illustrate the mechanisms used to secure coordination in the health care sector, which could be said to be equivalent to hospital care or post-trauma care in road traffic injury prevention.

In Bdeir and colleagues’ (2014) examination of inter-organisational coordination for disease outbreak response, the centrality of the coordinating agency enhanced coordination. It increased information sharing flow (Bdeir et al., 2014). A year later, Beatty and colleagues (2015) investigated the hospital-local health department coordination process. They found that a fifth (20.6%) of the work involved coordination. This study saw coordination as being a distinct process, dissimilar to “cooperating”, “collaborating” and “networking” (Beatty et al., 2015).

Two years after Beatty and colleagues’ study, Aller and colleagues (2017) examined a clinical coordination process. They found feedback mechanisms to contribute to clinical coordination processes. In this case, a critical success factor appeared to be the existence of specialty care centres (Aller et al., 2017).

It is therefore assumed here that government-community coordination of road safety can be conceptualised in terms of workflows, that is, processes followed by work units to achieve road safety outcomes.

Knowledge gap

Given the paucity of empirical literature specifically dedicated to the government-community road traffic trauma prevention coordination process, this study sought to address the following research questions (RQs) through empirical inquiry:

-

How do experienced coordinators in both government and civil society in the OECD conduct coordinated work to prevent road trauma?

-

What work models do they use to conduct coordinated work?

-

What do they consider to be the critical success factors for coordination aimed at behavioural change?

Methods

Research framework

To gain in-depth understanding of both the workflows in government-community coordination and the success factors, this research program adopted a qualitative research approach, employing ethnographic interviews and content analysis techniques.

The recruitment process was guided by snowballing sampling techniques. This exercise started with the construction of a sample frame. The initial contacts helped to establish a database of other potential study participants.

Participants

The present study focused on the interaction (linkages) between government programs and community-based activities. To unearth information about the nature of this type of coordination, the inclusion criteria for the study participants were as follows: a) program coordinators with at least five years of such experience; b) experience with local level program interaction; and c) residing in best performing nations in terms of road traffic injury prevention (by road deaths per 100,000 population). The 2009 and 2015 WHO Global Status reports on road safety were used to select these nations (see Recruitment).

Recruitment

The WHO Global Status reports on road safety have consistently shown that the best performing countries are also OECD members. Therefore, this study focused on OECD member countries. To methodically narrow the study focus down to the absolute best performing nations, only those OECD member countries with road traffic fatality rates equal to or below 7 deaths per 100,000 people were included.

This filtering was possible thanks to the 2009 WHO Global Status Report on Road Safety (see Country Profiles, pp. 49-226) and its iteration in 2013. Due to the wide error margin in these reports, the road traffic fatality rates reported for the OECD countries were averaged. For instance, in the 2009 WHO report of road traffic fatalities, Australia was said to have 7.8 deaths per 100,000 population (2007 data). Four years later, Australia was indicated as having one of the lowest road traffic fatality rates in the world at 5.4 deaths per 100,000 population (WHO, 2013). Its average road traffic fatality rate over the 2009 and 2013 reports was 6.6 deaths per 100,000 population.

Further country-specific searches identified counties and municipalities within the best performing OECD nations in terms of road safety, in most cases, through their own websites. The Contact Us forms on these sites were used to establish initial contact with community groups and road safety administrators within local governments. The countries ultimately represented in the study were Australia, Finland, New Zealand, Sweden and the UK.

Out of a total of 56 stakeholders invited to participate in semi-structured interviews, only 22 (39% response rate) made themselves available for recorded interviews by the deadline, despite subsequent invitations attempts and three reminders. To newly introduced referrals (snowball sampling), an e-mail was initially forwarded with details of the study and the inclusion criteria. Subsequently, the source contact was notified of the failed attempt to recruit the professional, in the hope that direct contact between the candidate enrolled in the study and the referral might yield a recruitment. This increased the flow of information between the referrals and the researchers. However, in a large number of cases, the referrals did not meet all inclusion criteria (see Participants).

Sample characteristics

As shown in Table 2, over half (15 of 22) half of the interviewees were Australians and almost half (12 of 22) were Administrators as defined by the ANZSCO (Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations) occupation categories (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022). The category of Administrators included local Council Officials and Community Officers with administrative job roles in charge of project management. Both Administrators and Managers (mostly line and mid-tier managers) were employed by local level/municipal governments. Recreation Officers were largely employed by community and interest groups. They participated in advocacy and program partnership development activities.

Data collection

An interview guide (Given, 2008) was designed and forwarded to the interviewees prior to the interviews. It explained the purpose of the research, the concept of consent, the nature of the semi-structured interviews, the participants’ rights and the manner the information would be used. In addition, the interview guide described the type of questions (open-ended and probes) to expect in the interviews.

The semi-structured (Harvey-Jordan & Long, 2001), ethnographic interviews (De Leon, 2005; Heyl, 2007; Spradley, 1979) were conducted by the principal investigator by phone and audio Skype. These approaches were selected for several reasons. The ethnographic interviews were thought to be ideal for gaining access to the specific context under investigation, that is, community-government interactions aimed at preventing road traffic injury. In addition, ethnographic interviews had the potential to help the researchers to discover a culture, thus unveiling complex patterns of behaviours or coordinated work models (Agar & Hobbs, 1982).

All interviews with respondents residing outside Australia were conducted over Skype, except for those conducted with interviewees in New Zealand. These voice exchanges were all audio-recorded with the consent of the interviewees onto a Forus FSV-510 Plus voice recorder.

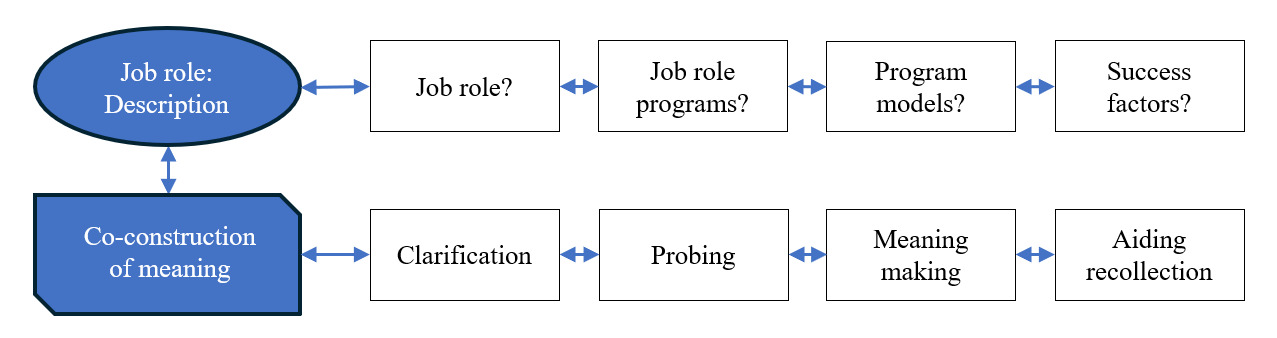

The ethnographic interviews flowed from generic, open-ended questions to probes as shown in Figure 1. There were two main phases in the interviews, namely: identification and expansion on job role, followed by co-construction of meaning. This strategy compensated for the lack of observation, typical of ethnographic interviews (De Leon, 2005). Further compensation for the lack of participant observation was the fact that both researchers had worked in the community-government road traffic injury prevention context in addition to holding PhDs in strategy and management (road safety).

The role expansion section involved two sub-sections. The first sought to identify programs or projects undertaken by the interviewees under their job roles. This was intended to search for a context for further exploration. This led to the identification of coordination models and their success factors, in the opinion of the respondents.

The most enriching section of the interviews constituted the co-construction of meaning. In this phase, both the interviewer and the interviewee participated in unearthing meaning from the experience. Great care was taken for the interviewer not to influence or cause the interviewee to stop being descriptive. The interviewer was cautious not to lead the interviewees into the path of prescription. To this end, the clarifications and probes were assisted by attempts to elicit actual moments or instances of lived experience for each perception or opinion offered by the interviewees.

In total, 22 participants were interviewed. Interview length ranged from 20 minutes to over an hour (1 hour, 17 minutes) (x̄ 35 mins).

Data analysis

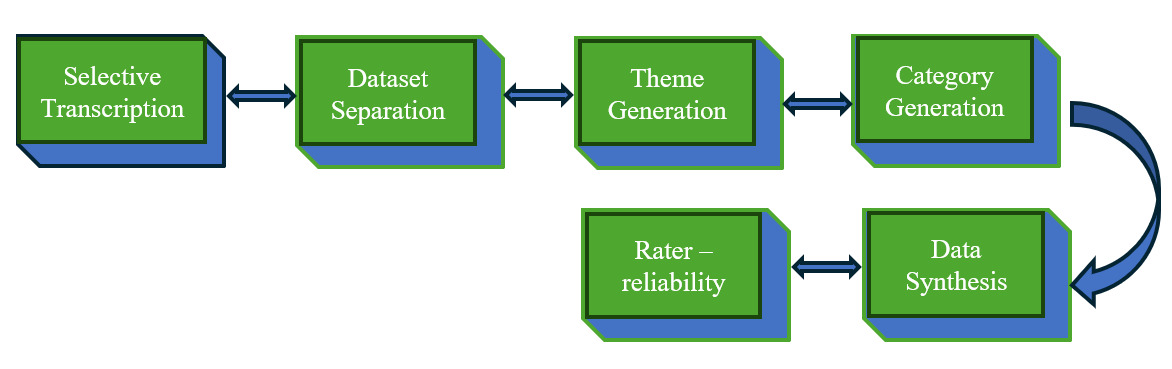

The process of data analysis (over 12 hours of audio recordings) began after the first three interviews. Its main purpose was to address the research questions (i.e., how community-government coordinated work occurred; the work models adopted for coordinated work; and the critical success factors for the coordinated work models). On the other hand, the first three interviews allowed the research question to be re-focused to unearth the most relevant details. To this end, the following data analysis was adopted (Figure 2).

Once the quality of the recordings on the Forus DVR Manager 2.0 were deemed satisfactory, various attempts were made to transfer the audio data onto NVivo10. These transfer tests failed due to the incompatibility between the two software packages. Therefore, manual, open coding (see Jacobs, 2014; Myron et al., 2018; Wilson, 2016) was adopted to transcribe the descriptions of coordinated work models (community-government coordination workflows) and the mentions of critical success factors for the coordinated work models.

In this case, every unit of meaning (i.e., each full utterance) was listened to a number of times to initially identify relevant references to workflows or success factors for coordination models. These relevant references were deemed to be descriptive mentions of aspects directly related to how coordination between road safety programs was established, sustained and evaluated. For instance, if a respondent referred to the establishment of links between road safety programs, the relevant phrases were written down. This iterative process was aided by a simple research query, namely: a) is this interviewee describing a workflow or alluding to a critical factor in the success of coordination? If the answer was affirmative for either question option, the utterances used by the interviewees were written down. This phase resulted in the transcription of all relevant references to both coordinated work models or workflows and critical success factors for community-government coordination at a local level.

At first, there appeared to exist a wide variety of both workflows and critical success factors, with each interview generating three to four work models. These seemed to be project-specific. Therefore, content analysis techniques were employed to generate commonalities across model descriptions and factor references.

Initially, the data were separated into two broad sets: workflows and factors. The subsequent review of the transcripts for the workflows allowed differences to be revealed. In some cases, the workflows seemed to be data driven. In other cases, road traffic injury issues appeared to drive the flow of work behaviour patterns. These disparities were assigned labels (themes). For example, one such theme was data-driven. The other theme was government challenge. A third theme was issue proposal. This discovery allowed other themes to be searched for. As the themes were revealed, these became the codes under which the model descriptions were placed. This narrowed down the number of workflows, as commonalities across models soon became apparent. Further examination of the themes allowed workflows to be separated into theme-based categories (Wilson, 2016).

The approach described above was adopted in relation to the critical success factors for coordinated work. However, it yielded a much wider range of factors than the workflows. The exemplars (direct quotes) about the arrangements, tools and attitudes contributing to successful joint community-government work in road traffic injury prevention or reduction were then synthesised through meta-ethnography.

Through the use of meta-ethnography, the exemplars (references to critical factors) were listed in the sequence of the recordings, using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. This allowed themes and metaphors to be generated and a long list of exemplars to be synthesised (Table 3). Subsequently, additional exemplars were placed under themes from which metaphors (images of, symbols of) were generated, thus affording the development of in-depth interpretations of the contexts represented by the whole of the interviews.

The exemplars were compared and subsequently translated into one another (Noblit & Hare, 1988). Because the quotations were deemed to be analogous, a Reciprocal Translation Synthesis (Noblit & Hare, 1988) was adopted. This synthesis approach draws analogies from comparable qualitative material where no refutation or a line of argument appears apparent (Noblit & Hare, 1988). The result of the analogies (comparisons) represents a summary (translation) of the key ideas in all accounts (exemplars).

In the case of the critical success factors in G-C RTTP coordination, the exemplars did not, in a large number of cases, seem to be refuting one another or presenting an argument, lending themselves best to reciprocal translation as defined in a number of recent replications of Noblit and Hare (1988) (see Franzel et al., 2013; Hildebrandt et al., 2019; Lawton et al., 2016). This synthesis process is illustrated in Table 3.

Rater-reliability

The interview recordings were shared between the study authors. The principal researcher presented the initial syntheses of the recordings to the other authors who reviewed the syntheses for accuracy. This process was iterative and yielded small adjustments to the syntheses. Once the authors were satisfied that the syntheses accurately described the experiences of the interviewees, the interviewees were contacted to inform them of the need for them to independently review the syntheses.

The syntheses (see Results) were then e-mailed to the interviewees for validation. This review was guided by three validation questions, specifically:

Do you think that:

-

your anonymity has been compromised by the reference style used in the text;

-

the contents of the text accurately represent your experiences (if you are able to recognise your context); and

-

you can add any additional contributions?

One respondent requested the removal of details for a specific program. Apart from this modification, the respondents expressed agreement with the accuracy of the descriptions included in the syntheses. This endorsement validated the syntheses presented in the Result section below.

Results

This research paper sought to address three research questions. These elicited evidence of the way OECD-based experienced coordinators in both government and the civil society conducted coordinated work. In addition, the research questions required the unearthing of models of G-C RTTP coordination for road trauma prevention. Furthermore, this study research questions sought to investigate the critical success factors for G-C RTTP coordination. These questions are addressed below.

This section reports the results of the syntheses in three ways. The first sub-section describes the rationales for coordinated work. The second sub-section shows the actions undertaken to create linkage opportunities. This sequence is herein referred to as workflow patterns (see Bayramzadeh et al., 2018; Ozkaynak et al., 2015). Subsequently, the critical success factors for G-C RTTP coordination are outlined.

Rationale for Community-Government coordinated work

The opportunities to establish coordination occurred in a range of different ways. In some cases, these happened as a result of mandated requirements. In this case, there might be “… an agreement from our politicians that we are to work for a better safety … it is a decision from our political leaders … and we have some money for safety measures …” (F, Swe, Administrator). In fact, there might be a “… local transport plan [which] specifically sets targets for casualty reduction … that’s in line with the government strategy …” (M, UK, Administrator). In other cases, the establishment of coordination was found to have been less formal. In this sense, practitioners may simply have "… identified a couple of the schools in the areas that [would] be affected [by the trends drawn from the crash data] … we [went] to talk to the person in charge … in those cases both principals … they [were] quite happy to support us … they dedicated the person in each school to help us to identify what need[ed] to be done … and then we just included those people in our group … I explained the rationale behind our suggestions … " (M, NZ, Professional). Indeed, these exchanges were thought to be fairly straightforward, so long as stakeholders were prepared to approach each other.

Put another way, the interactions between the program participants were “… semi-formally …[involving the need to] basically … [talk] to the principal … [who would assign a] teacher … [to be] part of your group … [who would be] included … in our meetings …” (M, NZ, Professional). Much of the informal ways to start coordinated work stemmed from a commitment to coordinated work as illustrated by one of the interviewees:

“… we try as best as possible for all of our programs … to be multi-disciplined … for example, school waste programs that involve a large component of education, but they’ll be complemented with engineering, infrastructure improvements … plus they’ll be coordinated with enforcement from either our local law officers … [or] police …”

F, Aus, Administrator

Indeed, the rationales for coordinated work in road traffic trauma prevention at a local level appeared to be target-oriented. Depending on the target and the instrument used to convey the behaviour changing messages, the coordination of road traffic trauma prevention had a different rationale. In Table 4, the rationales are further segmented into constructs or metaphors of the rationale and, the rationales differed across the seven cases. There were times when joint action served as a conduit for reform rationalisation. This allowed officials to explain the reasons for the enactment of new laws such as the mandatory helmet laws. There were other times, however, when public approval of new and existing laws was the pursuit in coordinated work.

Workflows

Whilst the comments made by the interviewees did not appear to suggest a large number of differences across the countries in the manner coordination flowed, there were differences in the workflows related to the purpose of the coordination, the participants and the targets. For instance, in those cases where crash data dissemination was the goal of coordination, the workflow pattern would be different from the joint actions undertaken to raise awareness to the enactment of new laws. Indeed, there were those who relied upon crash data. One interviewee indicated that “… if [they saw] that there [was] a spike, [they] drill[ed] down into that data …” (F, Aus, Administrator).

However, another interviewee suggested no reliance on crash data in government coordinated work, explaining that “… we don’t rely on the crash statistics … that does not underpin what we do …” (F, Aus, Administrator), explaining that the workflow was funding dependent rather than crash data oriented.

“… it is not … this is a project, let’s do it … it is not how we do it … it’s highly dependent on the opportunities that become available on a monthly basis … unless we have a budget, that job won’t get done.”

F, Aus, Administrator

The aforementioned disparities explained the existence of different workflows for different types of coordinated work. Therefore, there did not appear to exist a standard model of conducting G-C RTTP coordination (Table 5).

Critical success factors

The interviewees reported seven common critical success factors, which shaped coordination between government officials and community groups in some OECD countries. These were said to be: a focus on coordination-enhancing actions; resilient cooperation; sharing time together; clarity about partners’ job constraints and opportunities; commitment to conflict resolution; binding agreements and a unified approach. Other contributing factors appeared to be more context-specific.

Focus on coordination-enhancing actions

The interviewees in the present study seemed to suggest that the focus in successful G-C RTTP coordination should be on the actions required to establish the linkages across programs. In this sense, the study respondents appeared to reject the practice of identifying reasons and motivations for people to work together. Indeed, the findings suggest that the creation of opportunities for linkages outweighs all other precursors of coordinated work.

Moreover, the study results also point to an important lesson. The richness of the information generated in the initial stages of coordinated work determines the potential outcome of the subsequent stages, including the extent to which coordination may be conducted.

Resilient cooperation

The nature of the relationship across partners appeared to be one of resilient cooperation with enduring partnerships. This was the case in the UK where the government initially provided partnership grants, much like the model currently in use in one of the states in Australia (F, Aus, Manager), which has since withdrawn these grants. Although “…these grants have gone in the UK … in most areas of the UK there is a sort of partnership active …” (M, UK, Administrator).

Additionally, these enduring relationships featured assistance to lodge applications for funding provided by government institutions to community groups (F, Aus, Administrator), technical advice passed on to government institutions by community groups (M, Aus, Recreation Officer), and community voice through government external consultation processes (M, Aus, Recreation Officer).

Sharing time together

The respondents believed that there was a need to share time together. Indeed, it was thought that one needed to “… spend time with [partners to] … explain [your] ideas … [have the] willingness to share [ideas]…” (M, NZ, Professional). In this sense, frequent “… e-mails and meetings …” (F, Aus, Administrator) were thought to be helpful. Additionally, there appeared to be a need to exchange regular e-mail updates (M, Aus, Administrator) on the progress of assigned tasks.

This level of commitment to communication was said to reflect a keen interest in the issues (M, Aus, Recreation Officer). Indeed, stakeholders were said to contribute best when they had a genuine “… interest in road safety …” (F, Fin, Administrator). This sincere pursuit of issues related to road safety was said to be aided by local knowledge (F, Fin, Administrator). In fact, it was thought to be important that strategy coordination be informed by knowledge of the issues faced by the community [social research] (F, Fin, Administrator).

Partners’ job clarity

The interviewees reported the existence of clarity around the job of each partner as a key success factor. Basically, “… [local Councils] promote safe behaviour in the community [through media advertising] … and the police do high visibility enforcement …” (F, Aus, Administrator). In this case, the activities are coordinated so that one supports the other. In this sense, one partner “… would usually hold a … workshop prior to the learner log book run …” (F, Aus, Administrator). Essentially, knowledge of each other’s priorities appeared to create opportunities for coordinated work.

Willingness to resolve conflicts

The coordination of the various local level activities also involved challenges. The barriers ranged from disparate perspectives to institutional constraints. In the latter case, data and financial limitations appeared to be fairly predominant. In this sense, a respondent reported discrepancies across databases as an impediment to coordination. The “… [TAC, Police and Hospitals] realised the databases were covering different areas …” (M, Aus, Recreation Officer).

In other cases, the challenges seemed to pertain to work patterns and expectations, which were not clearly explained. In this case, the local authorities were perceived not to have ‘listened’ to the stakeholders despite a lengthy consultation process. In fact, they " ….were totally and utterly disappointed because … there were 48 initiatives in that road safety plan and only seven of them were appropriate for [a road user group]… we felt that although we had taken part in the process, we had been totally ignored …it did not represent the input we put in …" (M, Aus, Recreation Officer).

Nonetheless, the respondents were forthcoming with ways to address barriers. These included a combination of negotiation skills and deepening of understanding of each other’s cultures. Essentially, barriers were thought to be able to be overcome through a united, logically framed voice and willingness to listen to the other parties, the identification of commonalities and the collective development of knowledge about the stakeholders’ strengths, weaknesses and intended outcomes.

In fact, having a holistic perspective was thought to be helpful. It was thought essential that all stakeholders acknowledged that “… road safety is everybody’s business …” (F, Aus, Administrator). Indeed, “… unless you have people interested in the issue, you won’t get anywhere …” (M, Aus, Recreation Officer).

“… at the beginning they did not agree … they had a lot of different perspectives … there were a lot of negotiations … eventually … they reached consensus …”

F, Aus, Manager

“… it’s about setting out and finding what the common goals are right from the beginning and setting out quite clear guidelines to what the working group’s role is, what their purpose is, what the goal is, what the expected outcomes are … identifying desired outcomes … and having a way to quantify them …”

F, Aus, Administrator

Binding agreements

G-C RTTP coordination across programs was found to be beneficial on a multitude of fronts, not least the provision of an opportunity for community groups to access funding. However, the allocation of these benefits was thought to require management. This was said to be accomplished through written, legally binding agreements, which were issued to community groups found to “… have the capacity to … deliver programs …” (F, Aus, Manager).

The management of funding opportunities was equally achieved through the existence of regional staff whose task it was to assist community groups to deliver programs at a local level (F, Aus, Manager). In some cases, these and other officials had the task of engaging with stakeholders built into their job description. In fact, it was said to be part of job descriptions to engage with stakeholders.

“… it is part of my job, it’s written into my job description that I liaise with the various stakeholders … the only mandate is that I get evaluated annually on my job performance … so it’s a vital part … to ensure that I keep good relationships with all of our stakeholders, whether they be our internal departments … or external professional stakeholders and also community groups …”

F, Aus, Administrator

“Most importantly, there appeared to be a clear appreciation of the positive impact of community groups’ ability to be incorporated in the road injury prevention campaigns. Community groups were able to reach the ‘head space’ of road users. In addition, these civil society groups were found to have been useful in providing government programs with timely and accurate advice related to risk factors affecting sections of the community demographics. In these community groups, there were often champions of causes who could drive the delivery of the programs at a local level”

F, Aus, Manager

Unified approach

In all coordination modes, the key ingredient appeared to be ‘… a unified approach …’ (M, Aus, Manager). This uniformity in perspectives was achieved in ways that befitted the organisation’s policies and community group capabilities. In some cases, this meant starting with a project approach, which invariably was holistic in nature.

In other cases, it meant a more basic, mundane examination of the crash data, which were not universally used as a starting point. However, in the latter case, unless there was a sense of urgency in the trends shown in the data, little action often resulted. Nonetheless, the coordination models showed key common features, namely: each stakeholder had a clear role to play; stakeholders were open-minded and willing to have others address parts of the issues; stakeholders understood the need to prioritise programs due to limitations in resources; and planning made a notable difference.

Discussion

The present study enriches the road traffic injury prevention coordination empirical literature in a number of ways. Firstly, it is now known that road treatment activities are coordinated differently from educational activities. Engineering interventions in road traffic injury prevention are coordinated in a linear manner, which enlists a range of stakeholders in a non-circular way with one expert group sequentially adding value to a project. Community group coordination, however, tends to be circular with engagement across and between various levels of expertise in a collegial manner.

The current study has illustrated the value of cooperation and commitment to communication in the sustainability of coordination across road injury prevention programs. Moreover, this paper has established that coordination across stakeholders at a local level is characterised by resilient, enduring relationships, job clarity, a variety of coordination models, and the availability of funding to forge partnerships.

Most importantly, this study has shown the need to develop negotiation skills and clarify expectations from the outset to manage potential barriers to coordination. Indeed, this examination has shown that G-C coordination creates opportunities for all stakeholders. This is realised when a holistic approach is adopted by road safety officials and stakeholders alike. The current study reaffirms a number of previously made recommendations. It reiterates the WHO’s request for funding to be made available to relevant government agencies to enable these institutions to deliver road traffic injury prevention programs (Peden et al., 2004), admitting that funding can be hard to reach in low- and middle-income countries (WHO, 2009).

This challenge has been shown in the current study to be addressed in two significant ways. Firstly, the present study has illustrated a case of stakeholders participating in partnerships by bankrolling activities designed and delivered by other stakeholders. Secondly, one participant indicated that their salary was paid for by an insurance scheme. These and other adaptive strategies have enabled the study participants to deliver road traffic injury prevention programs, despite the availability of limited funding.

Furthermore, the current study endorses the socio, ecological model designed by May et al. (2008) on two key fundamentals. Road traffic injury prevention must move away from specialism (May et al., 2008). This constrained thinking, which emphasises the adoption of narrow approaches (May et al., 2008) was not supported by the participants’ insistence on a holistic approach to the coordination of road traffic injury prevention.

Additionally, the manner in which communities are reconnected with road safety (May et al., 2008) is illustrated in the current study through the various coordination models adopted by the study participants to suit the nature of the interaction (e.g., engineers/community groups versus administrative staff/community groups).

Study limitations

Although the coordinators and program administrators interviewed for this research paper had extensive experience of coordinated work, the modest number of respondents may have limited the study findings. A much wider pool of subject matter experts would have enriched the description of the workflows. It would have also provided a larger list of critical success factors. In addition, 15 of 22 interviewed were Australians and the overall findings may not be representative of the five countries included in the study.

However, given their long experience in coordinating work and the fact that there did not appear to exist any major differences across the countries in the way coordinated work was conducted, the likelihood of the descriptions listed in this study not being representative of a much wider context seems to be extremely low. Therefore, the limitations of the study do not seem to invalidate its findings.

Future research

Future research into road injury prevention G-C coordination should overlay the themes and metaphors with a theoretical framework or frameworks (i.e., ‘sensitising concepts’) to generate theories about coordinated road injury prevention programs in OECD countries at a local level with a much larger sample. This exercise can be significantly assisted by the use of a content analysis software package. Future research may serve low- and middle-income countries well by investigating the application of the coordination models presented in the current study. An additional future research endeavour may lie in the refinement of the concept of coordination (see Commitment to Engagement in Canoquena, 2013). This could mean identifying its dimensions in a quantitative manner quantitatively. It could also mean developing scale items to measure G-C RTTP coordination.

Conclusion

From the outset, this study identified the absence of research interest in government-community coordination aimed at reducing road traffic trauma. To bridge this knowledge gap, the present examination qualitatively coded the views of the interviewees and unveiled seven different rationales for coordinated work, six workflows for coordinated action in road trauma prevention and seven critical factors influencing the success of G-C RTTP coordination.

In so doing, it illustrated the nature of G-C coordination across road injury prevention programs at a local level in five OECD countries. In addition, it has shown that although there is a wide range of road injury prevention G-C coordination models, which tend to be purpose-specific, these share key features. These common characteristics are: the allocation of funding to forge partnerships, a unified consciousness to work together, the realisation of inter-dependence across stakeholders and programs, and a concerted effort to build capacity for community groups to deliver local level road injury prevention programs jointly with the police and government officials.

There were other critical factors, which merit further research as they were mentioned less frequently than the ones listed above. These included: a community development model, political support; detailed knowledge of the problem; the ability to envisage partnership success collectively, knowledge of each other’s approaches, commitment on the part of the authorities to follow through the ideas, having champions in their own sectors, a multi-stepped process with a great deal of dialogue, monitoring implementation, governments genuine interest in listening to the community’s views, government not seeing as marginalising some community group, genuine commitment to cooperation, common cause, common goal, advocates who can spread the word, officials having a stake on the resolution of the issues, face-to-face contact and the ability to broaden up roles.

Acknowledgements

This research study has been conducted thanks to the support and encouragement of Professor Barry Watson from CARRS-Q, Queensland University of Technology, Australia.

Funding

This research has not been funded directly. It was completed throughout one of the author’s Ph.D. studies.

Human Research Ethics Review

This research program has been approved by the QUT Human Research Ethics Committee in July 2014. Its approval number is 1300000478

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of the data, their availability is conditioned upon written consent from the research participants.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest arising out of this research and its publication.