Introduction

The rate of road crashes across the globe has been a cause for great concern over the years. Road traffic crashes have become the world’s leading cause of death by injury and the tenth leading cause of all deaths, and it is estimated that about 1.19 million people die annually as a result of road crashes (WHO, 2023). However, while mortality attributed to road traffic crashes has declined in high income countries, due to successful interventions like enforcement of seat belt use and safer design and use of roads and vehicles, deaths as a result of traffic crashes have increased in low- and middle-income countries. This has continued to have great adverse effects on the socio-economic growth of these countries. Over 70 percent of deaths from road crashes involve males; most of whom are between 15 and 44 years of age. This creates a lot of economic hardships for families as a result of loss of primary breadwinners (Population Reference Bureau (PRB), 2006) including people with skills to contribute to the development of these countries (WHO, 2018). There are also the indirect costs including the value of lost household services and lost earnings of survivors, caregivers and other members of family (Transport Research Centre, 2006).

Due to the increasing rate of loss of lives and property to road traffic crashes, there have been growing concerns with road transport safety in different countries across the globe. Over the years, various safety devices have been adapted into vehicle design to reduce the possibility of injury and death in case of road crash. One of the earliest and most effective safety devices is the seat belt, which was designed to reduce the risk and severity of injury in a crash. Seat belts were introduced in the 1960s as optional safety features in cars, and over time they have been proven to be very effective in reducing the severity of injury and possibility of death in case of road crash (Evans, 2004).

A large body of literature has established that seat belts are the most effective means of reducing fatalities and serious injuries when traffic crash occurs. In the event of a crash, a correctly used seat belt reduces the chance of death by 50 percent and has also been shown to reduce injuries in both high and low-speed crashes (Cunill et al., 2004). The effectiveness of seat belts in reducing the severity of injury to vehicle occupants involved in collisions has been proven in different studies (Evans, 1987, 1996; Febres et al., 2020). For instance, seat belts are found to be highly beneficial particularly in frontal crashes and run off the road crashes. These common crash types often result in serious head injury and with the probability of being ejected high, if seat belts are not worn (Evans, 1996; Mackay, 1997). Specifically, the use of seat belts has been found to reduce the risk of fatal injuries to front seat (60%) and rear seat occupants (45%) (Hoye, 2016). Furthermore, while wearing a seat belt can increase the likelihood of surviving a fatal crash by 45 percent to 73 percent, depending on the type of vehicle and seating position, (Blincoe et al., 2002; Routley et al., 2007), unbelted drivers are 8.3 times more at risk of a fatal injury and 5.2 times more at risk of a serious injury than belted drivers (Hoye, 2016).

However, whereas compliance rate is usually high in high income countries, it is generally low in low- and middle-income countries. For example, while seat belt use in the United States increased from 86.7 percent in 2014 to 88.5 percent in 2015 (NHTSA, 2016), in western Nigeria, compliance was reported to be 18.7 percent (Sangowawa et al., 2010) to 20 percent (Ismaila & Akanbi, 2010). Relatedly, a study of seatbelt use in Kumasi, Ghana showed that compliance rate was 33.2 percent for private car owners, 9 percent for taxi drivers and 8.3 percent for mini bus drivers (Afukaar et al., 2010). Further, in India, Save Life Foundation (2017) reported a seat belt compliance rate of only 37 percent and noted 28 percent of those who wear seat belt do so in order to avoid fines.

Various factors have been reported to influence compliance with seat belt laws in different parts of the world. For instance, drivers already violating a statute are less likely to be compliant. Driving without a valid drivers’ licence, alcohol-impaired driving and failure to obey speed limits have been statistically associated with non-compliance (Popoola et al., 2013; Steptoe et al., 2002). Socio-economic factors like income, level of education, age and area of residence have been found to influence seat belt use. For example, Shinar (1993) observed associations between income, age and level of education with rate of seat belt use. Sullman et al. (2002) and Malomo (2014) also observed that age and driving experience were significantly associated with aberrant driving behaviours like non-use of seat belts and other highway violations. Similarly, Clarke et al. (2010) and Strine et al. (2010) noted that less educated people are less likely to wear a seat belt. Likewise, Sheveland et al. (2020) found that attributes like being younger, male, single and living in rural area reduced the likelihood of use of seat belt while being a parent, having previous crash history and higher level of education increased the likelihood of seat belt use. Van Hoving et al. (2013) observed that drivers from high income areas were three times more likely to wear seat belt than those from low income areas.

Reasons given for not using seat belt have also been examined. The main reasons drivers adduce for non-use of seat belt include frequent stops, driving for short distance, forgetting and discomfort of seat belt use (Popoola et al., 2013; Sheveland et al., 2020). Other reasons include fear of being trapped after a crash, unlikeliness of being involved in a crash, lack of belief in effectiveness of seat belt and dislike of being told what to do (Begg & Langley, 2000; Sheveland et al., 2020; Simsekoglu & Lajunen, 2008). In addition, in Nigeria, ignorance and poor enforcement have also been found to be important factors responsible for low seat belt use (Ismaila & Akanbi, 2010).

Road safety crisis in Nigeria

In Nigeria, the situation is of serious concern. Alarming statistics from the Federal Road Safety Commission (FRSC) showed that between 1960 and the first quarter of 2002, 258,505 persons died as a result of crashes on the road. From 2000 to 2006, 98,494 road traffic crashes occurred, of which 28,366 were fatal and resulted in 47,092 deaths (FRSC, 2009). From 2006 to 2013, the FRSC recorded a further 41,300 deaths from road traffic collisions in the country. Also, using data from available news reports, Ukoji (2016) noted that between 2006 and 2014, out of a total of 61,090 violent deaths recorded in Nigeria (from road crashes, fire/explosions, crime, insurgency and so on) 15,000 people were killed in road crashes. However, noting the paucity of reliable road crash data in the country, WHO (2023) estimates that 36,722 people in Nigeria died in 2021 as a result of road traffic crashes, an estimated rate of 17 per 100,000 population. This is one of the highest rates in the world. Commercial vehicle drivers and their passengers are known to make up the largest group of fatalities on Nigerian roads and most fatal crashes resulting in death and serious injuries often occur on long distance journeys, due to the tendency for higher speeds and greater risk of driver fatigue (Adejugbagbe et al., 2015).

The use of seat belt was made mandatory in Nigeria in January 2003 in response to the alarming rate of fatalities from road crashes. The FRSC Act of 2007 and the National Road Transport Regulation 2012 also stipulated that every motor vehicle be fitted with front and rear seat belts and child safety seat, that all occupants must be secured while a motor vehicle is in motion. Not wearing a seat belt while driving carries a penalty of ₦2,000 (AUD2) fine and with possibility of impoundment of vehicle on failure to pay the fine. Note, this fine is likely to be from 6-16 percent of a driver’s weekly income as the average monthly salary for a commercial driver in Nigeria is ₦24,172 and ₦64,574 (AUD24.28-64.96) (WageIndicator, 2024).

While several past studies have reported low level of compliance in Nigeria, particularly among commercial vehicle drivers, strong efforts have been made by FRSC in recent years to enforce the use of seat belt on Nigerian highways. It is therefore necessary to find out whether these recent efforts have yielded required results in the form of improvement in compliance.

This study was undertaken to evaluate the adoption of seat belt by commercial drivers and their perception on seat belt, specifically focusing on inter-urban commercial vehicle drivers in Ilorin. It is anticipated that the findings of this study will help provide information on compliance rate, improve understanding of factors influencing seat belt use and also help road safety management agencies to develop better ways of improving compliance.

Two hypotheses were set as follows

(1) Ho1: There is no statistically significant difference among the drivers in seat belt use based on their educational status.

(2) Ho2: There is no statistically significant difference among the drivers in seat belt use based on their age.

Method

Study setting and data collection sites

This is a cross-sectional study in which the data were obtained through a survey. A structured questionnaire was used to collect relevant data from inter-urban commercial drivers. The study locations were motor parks officially registered with the Kwara State Ministry of Works and Transport. Unregistered motor parks were not included in the survey because their operations are usually irregular and unpredictable. Ethical approval for the study was obtained in December 2019.

The study was conducted in Ilorin which is the capital of Kwara State, Nigeria. The city lies within Latitude 80 30ꞌ and 80 50ꞌ N and Longitude 40 20ꞌ and 40 35ꞌ E, covering an area of about 100km2. The city is in the transitional zone between the southern forest and northern savannah regions of Nigeria (Adediji et al., 2009; Usman et al., 2016) and is an important transportation link connecting the northern and southern parts of the country (Figure 1).

At the time of the study in January 2020, there were 16 officially registered motor parks within the Ilorin metropolis. These consisted of five public motor parks and 11 private motor parks. These motor parks are long distance bus and taxi stations with administrative/ticket offices, passenger waiting areas and vehicle loading stands from which vehicles depart to various destinations. A total of seven of these bus and taxi passenger loading stations were selected for the study. These included three of the five public motor parks comprising of Maraba Park, Kwara Express and Offa Garage Park. The four private parks selected are Winner’s Express Travels, De-Emirate, Omo Oro Ago Express and Exceeding Grace Transport. The seven selected motor parks had a total population of 270 registered drivers. This consisted of 152 registered drivers at the three government motor parks and 118 drivers at the private parks.

Study participants

A sample of 50 percent of the drivers from each motor park was used for the study, giving a total of 135 respondents. A sample of 50 percent was used because larger sample size reduces likelihood of errors and provides more accurate representation of the population. Simple random sampling technique was used to select the respondents. The questionnaire was administered at the selected parks by seven field assistants.

In accordance with the ethics requirements, the drivers were first approached through their unions for enlightenment on the purpose of the research. All the drivers belonged to either the National Union of Road transport Workers (NURTW) or National Association of Road Transport Owners (NARTO). The drivers were asked to fill a consent form indicating their willingness to participate in the survey and assuring them of the confidentiality of information and no potential harm. They were also made fully aware of their right to withdraw at any point in time and of their right to their information. Thus, the preliminary results of the research were eventually made available to the participants through their unions and park management officials.

Data collected and analysis

The data used for the study consisted of demographic characteristics of the drivers (age, sex, marital status, education level and income), regularity of use of seat belt, motivation for using seat belt and drivers’ perceptions about the need for seat belt in vehicles. Data were also collected on reasons for not using a seat belt and drivers’ perceptions about seat belt enforcement.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the socio-economics characteristics of the respondents, to examine the level seat belt use among respondents and to illustrate the rate of compliance. Ranking method was used to show the prominence of seven factors identified from literature that may deter the drivers from using a seat belt. The respondents were asked to score the seven factors from most important (7 points) to least important (1 point). The gross score for each factor was then used to rank the reasons/factors. To verify the hypotheses, chi-square tests were used to identify significant differences in seat belt use among drivers with different levels of education and of different ages.

Results

Demographic characteristics of inter-urban commercial drivers in Ilorin

All the invited drivers participated in the survey (N=135, 100% response). As shown in Table 1, all the respondents were males. It is not surprising that there are no female participants because driving a commercial vehicle is commonly considered a male occupation in Nigeria. The age distribution of the drivers shows the largest proportion (43.7%) were aged between 41-50 years, followed by 31-40 years (31%). Only a small proportion (3.7%) was above 60 years old. This shows the majority of drivers are middle aged and likely to have gathered much experience in life. It is therefore not surprising that the majority of the participants are married (77%). Education among the cohort was low with over half (57.0%) having less than secondary education, including 23.7 percent with no formal education. Driver income shows that most (56.2%) earn between ₦20,000 to ₦40,000, while only 16.4 percent earn above ₦60,000 per month. This is comparable to the national salary rates for commercial drivers in Nigeria (₦24,172-₦64,574 equivalent to AUD24.28-64.96 (WageIndicator, 2024)).

Regularity of seat belt use by commercial drivers

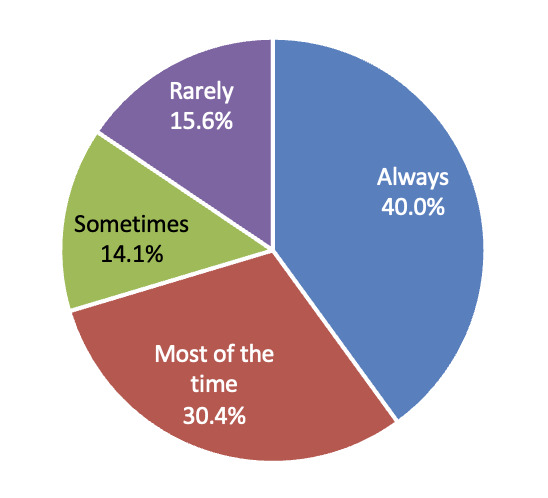

Investigation of the constancy of seat belt use by the commercial drivers shows only 40 percent reported always (at all times) using seat belts while driving and another 30.4 percent of the sampled drivers used their seat belt most of the time (Figure 2). Since seat belts are required to be worn at all times while driving it is clear that full compliance rate (40%) is low among the drivers.

Drivers’ motivation for wearing seat belt

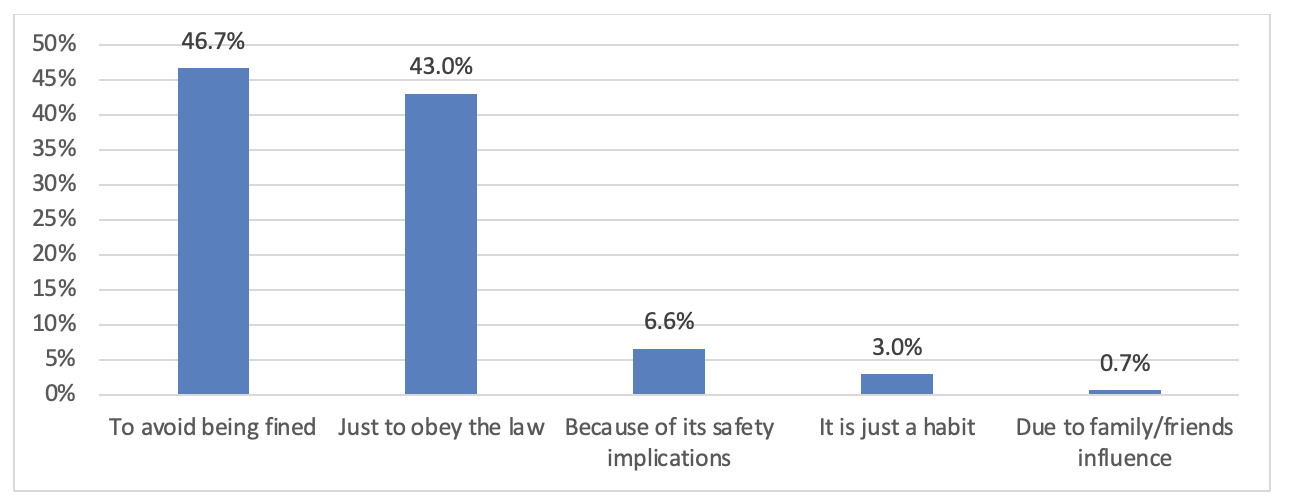

The study also examined the motivation behind the use of seat belt by the drivers and different reasons were given for their compliance. As shown in Figure 3, 46.7 percent of the respondents wore seat belts to avoid being fined while another 43 percent of the respondents put on seat belt just to obey the law. Only 6.6 percent of the sampled drivers wore a seat belt because of its safety implications.

Relationship between the demographic characteristics and seat belt use of commercial drivers

Table 2 presents the data on age and educational status of commercial drivers and their frequency of seat belt use.

Age and seat belt use

The results show that full compliance with the seat belt law is highest among the drivers above 60 years old. Although, those above 60 years formed just 3.7 percent of respondents, over half (n=5, 59.5%) always wore seat belts while driving. Further, drivers aged 51-60 years form the group with the second highest level of compliance with 45.5 percent rate of full compliance. The lowest rate of full compliance was among the younger respondents, aged 18-30 years.

Educational status and seat belt use

As shown in Figure 2, just 40 percent of the respondents wore their seat belts always (full compliance) of which 3.7 percent have tertiary education. However, since drivers with tertiary education constituted only 7.4 percent of all respondents, it means that full compliance rate is 50 percent among those with tertiary education. The rate of full compliance is therefore higher than average among drivers with tertiary education.

The least compliance rate is found among those with secondary education (n=14, 29.2%). Furthermore, Table 2 shows that 46.8 percent of those with no formal education fully comply with the seat belt law by always wearing their seat belts. For those with primary education full compliance is 44.4 percent. This is slightly higher than the average (40%) for all respondents as also seen in Table 2.

Test of hypotheses

Table 3 presents the results of the test of significant difference between demographic characteristics of the drivers and their seat belt use. The result of test of hypotheses shows that there is no statistically significant difference in the seat belt use among drivers with different levels of education (X2 (9) = 6.9, p= 0.86). However, there is a significant difference in seat belt use among drivers in different age groups. Higher rates of seat belt use were reported among the older drivers (X2 (12) = 23.1, p= 0.005).

Perception of the drivers on seat belts

The need for seat belts in vehicles

As shown in Figure 4, none of the respondents disagreed that seatbelts are essential in cars. As high as 62.2 percent of the respondents strongly agreed that seat belt is essential, while another 31.8 percent also agreed that they are essential.

Reasons for not using seat belt

Despite the recognition of the importance of seat belts by the majority of the drivers (94.0%), fewer than half (40.0%) fully complied with the seat belt law. Therefore, the drivers were asked to individually rate 7 possible reasons (factors) for which they may not use seat belt based on the significance of such reasons to them. The total score for each reason was then used to determine the rank (overall importance) of each reason as shown in Table 4. ‘Frequent stops’ was ranked the most important reason, followed by ‘fear of being trapped during accident’ and ‘dislike being told what to do’ while ‘lack of belief in effectiveness of seat belt’ was ranked least important.

Drivers’ perception on seatbelts enforcement

Active enforcement of seat belt law is essential for ensuring compliance by drivers. Thus, the respondents’ opinions were sought on whether the use of seat belt be made optional. Results show that over half of the respondents either disagreed (34.0%) or strongly disagreed (20.0%) with the idea of voluntary use of seat belt (Figure 5).

Discussion

Among commercial drivers in Nigeria, seat belt use is low (40%). However, the low compliance level observed in this study is still higher than those observed in other studies in Nigeria. For instance, Ismaila and Akanbi (2010) and Sangowawa et al. (2010), reported compliance rates of not more than 20 percent in their separate studies in western Nigeria. The significant improvement in seat belt compliance observed in this study when compared to previous studies may be attributed to the stronger enforcement drive embarked upon by the FRSC in recent years. On the drivers’ motivation for using a seat belt, most of the drivers used the seat belt just to avoid incurring the ire of law enforcement agents, rather than because it is safer to do so. It can be deduced that most of the drivers who comply do so not because of its safety effect. Rather they just see the seat belt as an encumbrance that must be endured to avoid breaking the law which carries a penalty of ₦2,000 (AUD2) fine and with the likelihood of the vehicle being impounded. Thus, it is common occurrence in Nigeria to see vehicle drivers struggling to put on seat belt while approaching law enforcement agents on the road. This is an indication that stronger enforcement will further motivate drivers to comply with the seat belt regulation.

Age of the drivers was statistically significantly associated with compliance with the seat belt law. This result is also in agreement with many other previous studies. For instance, the result is in line with the findings of Shinar (1993), Sullman et al. (2002), Malomo (2014) and Sheveland et al. (2020) who all found an association between age and compliance with traffic regulations. It is likely that this result is because older drivers are more mature, more experienced and less likely to exhibit aberrant behaviours compared to younger drivers (Bucsuhazi et al., 2020; Ucinska et al., 2021).

No statistically significant difference was found in seat belt use among the drivers based on their level of education. However, compliance was found to be higher among the small number of drivers with tertiary education. This result partly agrees with the findings of previous studies. For instance, the higher compliance among drivers with tertiary education agrees with the findings of Shinar (1993), Clark (2010) and Strine (2010) who all found an association between higher levels of education and seat belt use. This result also agrees with the findings of Kulanthayan et al. (2004) who observed that highly educated drivers (tertiary) comply more than those who are less educated (secondary and below).

Furthermore, the findings indicate there is high awareness on the importance of seat belt among the drivers. This recognition of the importance of seat belt may be connected to the high proportion of educated people among the drivers. This is because most drivers (76.3%) had at least primary education. Therefore, their low level of compliance may be attributable to other factors like the inconvenience attributed to seat belt use and inadequate enforcement.

Drivers gave various reasons for not using seat belt, with the most important reason being the frequent stops they make. Commercial vehicle drivers in Nigeria often make numerous stops for passengers to disembark and embark which could be an important factor for non-usage of seat belt. The inconvenience of continuously unbuckling and buckling of the belt is likely to be a source of irritation to the drivers. Also, some of the drivers openly expressed the fear of being trapped by seat belt in a burning or submerged vehicle during a crash as being a factor for their non-compliance. This result is supported by the findings of Simsekoglu and Lajunen (2008), Ismaila and Akanbi (2010), Popoola et al. (2013) and Sheveland et al. (2020) who observed that various factors including frequent stops by drivers, lack of belief in effectiveness of seat belt, fear of being trapped, poor enforcement and belief in unlikeliness of crashing as being responsible for non-use of seat belt.

On the drivers’ perception on seat belt enforcement, only about half (54%) of them support the enforcement of seat belt use. This is also an indication that a lot of the drivers who comply do so to avoid breaking the law rather than because of its safety implications. This gives credence to the potential roles public enlightenment and stronger enforcement can play in motivating drivers to comply with the seat belt law.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study provides insights into a large sample of commercial drivers in Nigeria. Given the high rates of fatal crashes among this cohort and the potential benefits to be gained from greater seat belt use, the findings from this study help to understand both rates of use, but more importantly, why drivers are not using seat belts. These insights will help inform road safety action in Nigeria. Specifically, greater enforcement is likely to lead to increased compliance. In addition, the attitudes of drivers about the effectiveness of seat belts to protect them in a crash may be directly addressed.

The major limitation is the self-reporting nature of the study which is subject to social desirability bias. Thus, some respondents might have provided answers to present them as socially responsible rather than being honest. This may have influenced the exactness of some of the results recorded in the study. Nonetheless, self-report is most appropriate for this study which required data on respondents’ perception developed from personal experience, which could not be obtained through researchers’ observations.

Another limitation is the coverage of the survey which was restricted to only the officially registered motor parks, while the unregistered parks were not considered. This might have in some ways reduced the generalisability of the results. However, restricting the survey to the registered parks ensured unbroken access to the respondents. This would have been very difficult in the unregistered parks where operations are irregular and unpredictable.

Conclusion and recommendations

The findings show that despite efforts at enforcement, compliance with the seat belt regulation is still low among the commercial drivers. In addition to the low level of adoption, the drivers exhibited low impression about the effectiveness of seat belt in reducing injury and death in case of collision. It is therefore necessary to raise awareness and increase enforcement to improve compliance with the seat belt regulation. This will help contribute to reduction in traffic injuries and fatalities in Nigeria. Therefore, the following measures could be considered for implementation to increase compliance:

Awareness raising

Enlightenment programs should be organised specifically for commercial drivers in conjunction with their trade unions. This will help raise awareness about importance of seat belt and help improve their attitudes towards its use. This is especially important for the public motor parks which are dominated by small-scale individual operators who provide transport service.

Strengthening company internal policy on road safety

There is the need to enhance safety policy in transport companies. Transport companies have the corporate responsibility of ensuring the safety of their drivers and passengers and that they do not impose danger to other road users. Therefore, the use of seat belt should be made mandatory for their drivers in compliance with the seat belt law.

Raising penalty for non-compliance

Since a large proportion of the drivers wear seat belt to avoid the penalty of ₦2,000 presently imposed for violation, it is suggested that the fine be increased. This will likely encourage higher rate of compliance among the drivers. In addition, the fine imposed can also be categorised so that repeat offenders are made to pay higher fines.

Active enforcement

There is need for stronger enforcement to ensure that all drivers use seat belt while driving. The enforcement must be consistent and violators should be prosecuted when apprehended.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Mr Muhammed Hameed and Miss Victoria Adebisi for helping with data collection. We also appreciate the contributions of Professor I. P. Fabiyi for his time and efforts in reading through and helping to improve the standard of the manuscript. The authors also thank Mr Fola Dare for producing the maps used for the study.

Author contributions

The contributions of Dr Usman Bolaji Abdulkadir included the design of the study. He was also involved in the analysis of data, drafting of the manuscript and responsible for revising the manuscript at various times. Miss Toluwase Adebosin contributions included the conception of the study and collection of data. Her other contributions included review of relevant literature and drafting of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the article.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Human Research Ethics Review

The study protocol was approved by the University of Ilorin Ethical Review Committee on 12 December 2019 (UERC/ASN/2019/2116).

Data availability statement

The authors declare that no materials, data nor protocols were used.

Conflict of interest

The authors are not involved in any conflict of interest from funds, personal and institutional or any other relationship from this research.

.png)

.png)